“You ever hear the old saying, ‘I often wondered what was in a hot dog; now I know and wish I didn’t?’ Well, I guess the same goes for secession,” Alvin said.

The old rancher was straddling his caballo Duke on the slopes of Casa Grande peak in Big Bend. Keeping control of your land in 2015 was no picnic. Alvin hadn’t known there were that many poachers, polluters, land-grabbers, and water thieves in the world until Texas seceded from the Union five years earlier. Since then, it seemed like every nut group, polygamist sect, and survivalist organization in the old 49 states had pulled up stakes and headed for the new republic. Alvin and his partner Gus had bought their share of the old Big Bend National Monument fair and square, and with all the water wars going on these days, they weren’t letting anybody squat by their wells or steal their goats – not the drug runners, the half-assed militia groups, New Koreshians, or the steady flow of immigrants passing through on their way north to the American border.

The new president couldn’t guard the border any better than the old feds had done. Of course, these days, there were as many people trying to sneak out of the former Lone Star State as there were other folks sneaking in.

“I’m fed up with these trucks hauling God knows what and always trying to dump their loads around here,” Gus said. “Can you believe we’d ever see nuclear waste buried on this hallowed ground?”

“I never thought I’d see half of what I seen these past few years,” Alvin said. “Who’d a thought Texas would be verging on war with the U.S., arguing in Austin over dividing itself up into territories, or that we’d be needing a passport to go see Aunt Molly in Tulsa?”

Gravel pits, drill pads, dump grounds, injection wells, and smelter plants blossomed in the years after Texas seceded. It was hard to keep up with what was going on any farther away than Marfa, what with the government ban on so much information. But the ominous glow they could see on the rare clear night, from the direction of what at least used to be Odessa, was worrisome. Neither one had cared much for Odessa, so they didn’t lose too much sleep over that, except when the wind blew from that direction. What they did care about was all the traffic on the West Texas roads, clogged with regular folks and low-level smugglers now that the Trans Texas Mega Corridor had replaced the interstates and charged fees so high that only big-time dope dealers and oil companies could afford to send their trucks down it.

Duke whinnied and pricked up his ears as a tanker truck rumbled up a county road below. The driver had no idea he was being scoped from afar. Alvin and Gus dismounted and fetched Texas-madeTM automatic weapons from their saddle scabbards.

“Shhhh,” Alvin said, rubbing Duke’s nose. “We gonna have us a surprise party.”

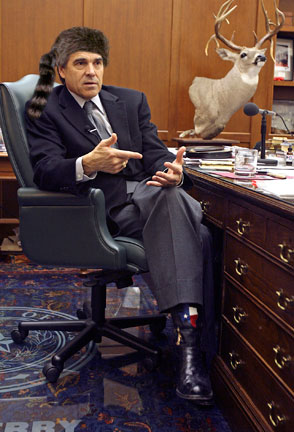

Only Gov. Rick Perry knows his true motives for hinting at secession during those April Tea Parties to protest federal taxing and spending, but plenty of others have wondered, and not just the late-show comedians: Was it political strategy? Deeply held beliefs? Or, like all those Texas Music singers who mention beer, chicks, and tacos in every song, just pandering to the crowd?

Only Gov. Rick Perry knows his true motives for hinting at secession during those April Tea Parties to protest federal taxing and spending, but plenty of others have wondered, and not just the late-show comedians: Was it political strategy? Deeply held beliefs? Or, like all those Texas Music singers who mention beer, chicks, and tacos in every song, just pandering to the crowd?

The Tea Party throng ate it up, but others questioned his motives – and

his sanity.

“The governor needs to get a psychiatrist because he’s gone crazy,” said Fort Worth resident Carlos Moore, a longtime ally of former U.S. Speaker of the House Jim Wright. “Secession would be complete chaos. It’s an asinine way for the governor to get some political attention.”

Democrats were delighted at Perry’s resulting loss of credibility, and even Perry’s own Republican Party members blanched at his rhetoric. “It’s not the kind of thing the governor ought to say without checking his facts,” said U.S. Rep. John Carter, a former district judge.

The Republican blogosphere had sharp words as well. “I guess the nutbars have found their spokesman,” wrote the conservative blogger behind Right-Thinking From the Left Coast.

Still, Perry wasn’t the first Texan to suggest breaking away from the mother ship. Like the rest of the South, the state seceded during the Civil War, and some folks, even today, long for a return to independence. After Perry’s secession remarks, a poll showed that 31 percent of Texas residents actually believe the state has the right to secede – and 18 percent want to.

As late as the 1990s, extremist groups like the Republic of Texas still argued that U.S. annexation was illegal and characterized Texas as an occupied nation. Even one of Perry’s challengers in the upcoming governor’s election has made secession his campaign’s rallying cry.

And it does seem to be true that, of all the states, Texas might have the best chance of going it alone.

So Fort Worth Weekly, ever respectful of the governor and his ideas, has set out to think the unthinkable – how would Texas fare as the Republic of Perryland?

At first no one understood why the University of Texas moved its main campus from Austin to a 500-acre pasture north of Gainesville. But the method behind UT’s madness became clear in 2014, when the school’s football team was allowed back into the Big 12 Conference under a special international agreement.

“It was no longer possible to motivate this Longhorn team to play the likes of Rice and TCU year after year,” Head Coach Terrell Owens said.

A tunnel under the Red River allowed the team bus to bypass the grueling border protocol established by the United States to control illegal immigration from Perryland. Just as the U.S. had once built a wall between Texas and Mexico, it built even higher and thicker barriers along the border with Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and New Mexico. Wading the Red was a mite trickier than the Rio Grande, what with the quicksand and all, but would-be Okie-Texans tried it all the time.

“The only thing I’d rather shoot than a wolf, moose, or polar bear is a damn Perrylander,” U.S. President Sarah Palin said during her 2013 inaugural speech.

The federal government had been outraged at Texas’ secession, of course, though there were some who were happy to see the state, with its boasting and its Bushes, disappear behind the wall. But U.S. officials eventually figured, why bother declaring war – the place would implode sooner than late. Instead, Perryland became the new Cuba, punished with sanctions and a commercial embargo that the U.S. urged its allies to honor as well. Establishment of new embassies in Austin by Uzbekistan and Liberia didn’t make up much for the hardships created when Texans realized they could now get Cocoa Puffs and Budweiser only on the black market.

With U.S. money, environmental regulations, occupational safety rules, disaster relief, border patrol, and all other federal vestiges removed, Perryland struggled. Establishing trade agreements and treaties was cumbersome, particularly for Perry, whose prior work experience was heavy on pleasing the religious right and making football bets with other governors but light on foreign policy.

The U.S. applied further pressure by clamping down on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Relinquish U.S. citizenship, and you lost your benefits. Many fled north of the Red River, back into America’s outstretched arms. But many others stayed, and plenty of adventurers flocked to the new frontier, willing to roll the dice in a vast and freewheeling republic. Mexican border security was ignored – there was no money or manpower to pay for patrols. Population soared. Perryland was a harsh place for the old, sick, and poor, but it was a mecca for industries grown tired of U.S. meddling. Lax regulations drew every type of smog-spewing, river-tainting, aquifer-poisoning industry looking for increased profits. In other words, kind of like Texas is now, only worse.

For the past decade, Russian academic Igor Panarin (no, really) has pinpointed 2010 as the year that mass immigration and a financial and moral collapse would bring on a civil war that would tear apart America. Under his scenario, the Republic of Texas would align itself with Mexico and several other renegade southern U.S. states.

Closer to home, secession is a vague notion that has been bandied about by Texans for years, sometimes seriously, usually as a humorous declaration of state pride. Allan Saxe moved from his native Oklahoma in the mid-1960s to become a political science professor at the University of Texas at Arlington. Not long after his arrival he began noticing “Secede” bumper stickers.

“We would probably be one of the few states that really could make it,” he said, citing the state’s vast acreage, agricultural production, minerals, oil, gas, coal, Gulf Coast ports, relatively vibrant economy, and large population and labor force – but he added that secession should never happen.

“There are many countries in the world much smaller than Texas,” he said. “Our economy is pretty self-sufficient. We have a large infrastructure of rail and highways. We have huge land areas that people could move to. Our governors have never been nearly as hostile toward immigration as other states have been, comparatively. Mexico would be warm to us.” The state already has an economy larger than that of many countries, not to mention greenhouse gas emissions that top those from all but six nations (no, really).

Texas’ political system is modeled after the federal government and could operate without massive overhaul, although a constitutional convention would be needed to provide a chief executive with powers. The state’s National Guard is voluntary and small, so an army would have to be created, as well as a new currency and laws to better reflect the republic’s wants and needs, Saxe said.

“Gun rights would be right up there,” he said. “Maybe we wouldn’t even have to have a concealed gun permit – we’d be walking around with guns on like in the old days.” Or like some young pro-gun activists on Saxe’s own UTA campus are lobbying for now.

On the other hand, Texas currently gets nearly a third of its budget from the federal government, about $51 billion in the 2008-09 biennium, said University of North Texas political science associate professor John Todd. Then there are Texas farmers, who received more than $16 billion in federal subsidies from 1995 to 2006.

Loss of U.S. funding would create budget shortfalls and hardships on the sick and elderly who depend on federal programs. The Social Security Administration allows Americans to maintain citizenship and receive benefits even when living in a foreign country. But those rules might not apply in the case of secession.

“To my knowledge there is nothing within Social Security that would say how we would handle a state that seceded from the Union,” Social Security spokesperson Wes Davis said. “It gets a little mind-boggling to say, ‘What if all of Texas were not part of the United States?’ It’s not something we want to imagine.”

A diverse economy might provide Texas with opportunities to overcome the loss of U.S. support, Saxe said. The state is home to major industries producing everything from computers to fighter jets. An established petrochemical industry and the largest domestic collection of oil refineries would give Texas some leverage with other developing countries, he said.

Oil analyst Gregor Macdonald recently concluded that Texas could be energy- independent. “Texas produces more oil than any other state and accounts for 19.7 percent of total U.S. output,” Macdonald wrote on his web site gregor.us. “Texas also produces more than 30 percent of the U.S. natural gas supply. Texas does consume a goodly portion of its own oil output, about 75 percent of what it produces. But it only consumes half of its own natural gas production. For secessionists, these numbers look good.”

Most people, though, view secession like a crazy uncle who walks around the neighborhood in his underwear.

State Rep. Leo Berman, a Tyler Republican and a fervent advocate of states’ rights, doesn’t want to be linked with talk of secession. Berman authored a recent bill that would exempt some Texas-made guns from federal regulation, and he was involved with other bills that assert state sovereignty under the U.S. Constitution’s 10th Amendment.

“We’re hearing from President Obama and his cabinet that they want to do things in the states that are not authorized by the U.S. Constitution,” Berman said. “We have to let Washington know what they can and cannot do.”

That was part of Perry’s rationale for hinting at secession. But asserting states’ rights is a wholly different topic, the legislator said.

That was part of Perry’s rationale for hinting at secession. But asserting states’ rights is a wholly different topic, the legislator said.

“Secession is an issue I don’t care to investigate,” Berman said. “I know it can’t be done. I don’t think it’s something we should even be talking about now.”

What’s wrong with discussing secession?

“During the Civil War the idea of secession came up, and they were branded traitors,” he said.

The right to secede was established at the Union’s inception as an important protection against an oppressive central government – not surprising, perhaps, since America fought a war to secede from the British empire. Thomas Jefferson, in his 1801 inaugural address, said, “If there be any among us who wish to dissolve the Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed.”

That idea had fallen by the wayside a half-century later, when Southern states started talking about actually severing their ties to the U.S. over the slavery issue. President Abraham Lincoln, in an early speech, compared secession to anarchy. But equating that rebellion to modern-day secession is comparing apples and oranges, Berman said.

“We’re a nation,” he said. “We can’t secede. There are too many interrelationships between states. Other states rely on us for oil and gas and high-tech equipment. Nothing in anything I said has anything to do with secession.”

Todd, the UNT professor, said there’s no law, treaty, or constitutional provision that allows Texas to legally secede. Saxe said it would be the equivalent of a declaration of war.

Fort Worth author and historian Rick Selcer said an independent Texas “would become a renegade state with no friends and be treated by the U.S. the same as Mexico, Peru, Guatemala, and any other state that is semi-respected and troublesome.”

Without the Army, Air Force, Navy, and nuclear weapons, Texas would be a sitting duck; our military complexes that crank out airplanes and hardware would falter as well, he said. “If you take away the U.S. demand, then Lockheed ceases to exist.” And how long would the United States sit idly by if Texas decided to start selling its military output instead to, say, Iraq?

Secession would cause major problems for the U.S. military: Beyond the loss of bases and contractors would be the problem of whether Texas soldiers could be counted on to fight the Lone Star rebels. More servicemen and servicewomen come from Texas than any other state, and they make up about 15 percent of U.S. nation’s armed forces.

Ed Brannum, a senator in the separatist Republic of Texas group, would not divulge what the military in an independent Texas would look like, other than to say it would be a force to be reckoned with.

“There are about 6 million well-armed rednecks within the Texas republic boundaries, and I do not know of any force larger in the world,” he said.

Shannon McGauley, a spokesperson for a Minutemen group based in Arlington, said that at any given time there are some 10,000 armed Minutemen in Texas who would be willing to take up arms for the independent state. He also predicted that thousands of out-of-state members of the group would swarm to Texas, guns in hand, ready to protect the border from invaders – not including themselves, of course.

Even Perry seems unsure about an independent Texas.

“We’ve got a great Union,” he said at the tea parties. “There’s absolutely no reason to dissolve it. But if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people, you know, who knows what might come out of that?”

Most people interviewed for this story felt certain about what would come of secession – chaos and doom.

Selcer, an adjunct political science instructor at local junior colleges, said his classes have discussed Perry’s idea. Classroom debates have included scrutiny of Brigham Young and Utah’s resistance to federal annexation in the mid-1800s and other states that have toyed with the idea of secession through the years. Secession in the 21st century could be disastrous, he said.

“It shows what an idiot Perry is for even suggesting it,” he said. “It’s like saying, what if we decided to bring back slavery?”

The U.S. by 2015 was working under the radar to bring about a “regime change” in Perryland. After all, smog drifting north from Mexico was merging with the black clouds billowing out of Perryland and casting a haze over much of Colorado and Oklahoma.

“I can see the smog from here,” U.S. President Palin said – from her front yard in Alaska.

Perryland further infuriated the U.S. by trafficking arms, aircraft, and military hardware to any nation or regime willing to plunk down cash. The U.S. had dropped its ties to Texas defense contractors but couldn’t shut down the plants. After that, Texas invited manufacturers of all sorts of handguns and personal weaponry to relocate here, a move loudly applauded by the drug cartels in Mexico, always major customers of Texas gun merchants.

Meanwhile, Galveston was just a memory. After rebounding from Hurricane Ike in 2008, the city was hit by the even tougher Hurricane Tina in 2012. Without U.S. disaster relief funding, the devastated island city was left largely in ruins.

The West Texas deserts had expanded – drought, exhausted lakes, and fouled aquifers had choked the landscape. Perry made lemons of lemonade, though, and leased the land to foreign pilot training programs as bombing ranges. As a state, Texas had already become a repository for hazardous and nuclear waste from across America; as a province of Perryland, it became the world’s dumping ground – for a profit.

Gus and Alvin often sat on the porch of their mountainside shack watching the green glow on the horizon and feeling the thump of shells hitting home from the student pilots’ planes. There wasn’t much else to do for entertainment, what with American TV stations being jammed and with millions of Lone Star women of all races having decamped after figuring out that the religiously rigid Perryland, like Texas of old, might be OK for men and dogs but was hell on women. Lots of black male Perrylanders, remembering the reasons Texas seceded the first time, joined them in the emigration lines.

It was getting to be a dangerous place to live, in more ways than one. Mexican drug cartels were moving in anywhere they could find remote ranchos with enough water to grow their crops. And when Gus started pulling three-headed fish out of the Rio Grande, the two old ranchers started thinking it might be time for them to leave as well, though it wouldn’t be easy. Mexico had become our best ally and trade partner, but Central American nations didn’t tolerate Perryland residents trying to move there full time. The people-smugglers known as “yankee coyotes” were doing a lot of business.

The notion that Texas came into the Union with a different set of secession rules from other states has been repeated here since Reconstruction. Shortly after Texas gained its independence from Mexico in 1836, its American expatriate leaders began pushing to join it to the United States. There was much bargaining between Austin and Washington and some talk of a treaty with special rules for Texas, if it came into the Union. But none of that language ever appeared in any of the laws that eventually did bring Texas in as a state.

The notion that Texas came into the Union with a different set of secession rules from other states has been repeated here since Reconstruction. Shortly after Texas gained its independence from Mexico in 1836, its American expatriate leaders began pushing to join it to the United States. There was much bargaining between Austin and Washington and some talk of a treaty with special rules for Texas, if it came into the Union. But none of that language ever appeared in any of the laws that eventually did bring Texas in as a state.

In 1844, Congress wanted Texas to enter as a territory. Texas pushed for statehood. This was the time of slavery compromises; Texas’ entry as a slave state was supported by southern states but rejected by Congress.

The political maneuvering got trickier with a dispute over how much territory Texas actually included. Texas claimed its border was the Rio Grande, all the way up to the river’s headwaters, through what is now New Mexico and Colorado. Old maps show a narrowing arm of territory continuing far north of the current Texas Panhandle. When Texas was finally brought in as a state in 1845, Congress included provisions that Texas could divide itself into an additional four states, as a way to make up for taking away some disputed territory north and west of its current borders.

But even though Texas could do it legally, the notion of slicing up the Lone Star State has never had much traction. Northern states fought against it after Reconstruction – they didn’t want the South gaining more power in the Senate. Through the years the issue has been brought up occasionally; Congressman John Nance Garner raised it while he was speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives in the early 1930s. More recently, in 1991, a pissed-off Panhandle legislator proposed that the area split off, but the bill was never considered in Austin.

There is also a U.S. Constitution issue. Article IV states that “no new states shall be formed within the jurisdiction of any other state.” So even if Texas wanted to carve itself up, there would be serious legal arguments against it.

As for the notion that Texas could secede legally, that issue appears to have been decided in a U.S. Supreme Court case in 1869. The actual case was relatively insignificant; some state bond-holders wanted to be paid, and the feds had no jurisdiction because the debts were incurred while Texas was in the Confederacy. The court ruled that Texas had never legally left the Union.

The court used the occasion to issue a very broad decision. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase wrote, “The union between Texas and the other States was as complete, as perpetual, and as indissoluble as the union between the original States. There was no place for reconsideration or revocation, except through revolution or through consent of the States.”

“The Civil War settled that issue,” said Felix D. Almaraz, a history professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio who has studied the secession issue extensively. “After the Civil War, it was determined through war battles and court cases that the Union is supreme over states’ rights. If Gov. Perry said what he said without any deep thought, it is a sign of historical illiteracy.”

Southern Methodist University political science professor Cal Jillson said Perry is “wrong on history in fairly radical ways.”

The secession movement, on life support for most of a century, has come out of its coma a couple of times in the last 20 years. In 1995, Richard Lance McClaren of Fort Davis said U.S. annexation of Texas after the Civil War was illegal. Convinced that the state was under occupation by a foreign country, McClaren founded the Republic of Texas and was named its chief ambassador and consul general.

McClaren and his bunch tumbled directly into legal trouble. The group filed liens against public and private property and sent letters to banks ordering them to transfer the state’s monetary assets to the new country. Group members were accused of burglaries, and Texas Attorney General Dan Morales asked for and got restraining orders against them.

Things came to a head in 1997 when McClaren and his followers kidnapped a couple of neighbors and held them hostage at his “embassy” – a trailer house and a couple of outbuildings. They demanded the release of members of their group who had been jailed earlier. After a weeklong standoff, McClaren surrendered and ended up in prison; another dissident was killed and a third was captured after a manhunt.

Various movements have continued the cause, the biggest being the Texas Nationalist Movement, a group that is adamant on secession but vague on how Texas would change with regard to public programs and taxes once it became a country. Their leader is Daniel Miller of the Beaumont area, and he jumped at the chance to get publicity after Perry’s remarks, saying the incident showed that his group’s secessionist movement had finally gone mainstream.

“People are starting to think about it,” Miller told the online publication Bayou Vixen (no, really) in a recent interview. “When everybody else is pointing out the problems, we’re the only ones who are pointing out a solution.”

But even he doesn’t buy into the governor’s sincerity.

“There’s no doubt that he did that for one three-letter reason – KBH,” Miller said, referring to U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, Perry’s main opponent in the Republican primary. “He has a political motivation, trying to paint her as the Washington insider. But regardless of what his motivations are, the horse is out of the barn now.”

Candidates typically lean toward their party’s extremes during primary campaigns and then toward the middle in general elections. Hutchison is seen as having more strength with Republican moderates, while Perry has more support among the conservatives.

Candidates typically lean toward their party’s extremes during primary campaigns and then toward the middle in general elections. Hutchison is seen as having more strength with Republican moderates, while Perry has more support among the conservatives.

Larry Kilgore, who is also seeking the Republican nomination for governor, made secession his top issue in runs against Perry in 2006 and against Sen. John Cornyn in 2008. He received about 225,000 votes against Cornyn and now says Perry might be trying to “out-secede” him because of that showing.

Kilgore, a telecommunications engineer in Mansfield, said he advocates secession because Washington is out of touch with citizens and government should be more local. He doesn’t want the feds mandating social service programs like Medicare and Medicaid, demanding that hospitals treat illegal immigrants, or establishing policy for public schools. Besides, he said, federal spending is “putting the U.S. on the verge of economic suicide. We have to get away from that.”

Kilgore would put the secession issue on a statewide ballot, and if voters approved the measure, Texas representatives would go to Washington and ask for the state’s release from the Union. “I could see us negotiating with them, and they would allow it, as more states would likely follow, and they would prevent civic unrest,” he said.

Former Texas congressman and Republican power broker Tom DeLay laid out a secession scenario in a recent TV interview, with another fractured recounting of alleged Texas history.

“Texas was a republic,” DeLay said. “It joined the Union by treaty. There’s a process in the treaty by which Texas could divide into five states. If we invoke that … the U.S. Senate would kick us out and nullify the treaty because they’re not going to allow 10 new Texas senators into the Senate. That’s how you secede.”

Jillson sees a different scenario. He predicted that Texas secession would motivate the U.S. government to move troops from the Fort Hood army base

to Austin.

“Who do you think would win that one?” he said. “Politicians can’t even agree on how to redraw districts when new census numbers come out. Do you think any Texas lawmakers will be able to sit down and carve up Texas into five distinct states? The fact that [DeLay and Perry] are even talking like this is just irresponsible and crazy.”

Alvin and Gus were finally fed up. They knew they’d get precious little government help in their retirement as long as they stayed in Perryland. Plus, there was Alvin’s niece Shaniqua to think about. She was a good hand around the ranch, but there had to be a better life for her than putting gas masks on goats.

Besides, pretty soon she’d reach the age at which they’d have to get her vaccinated with something called Gardasil, as required by one of Perry’s first executive order as president, right after the one requiring church attendance as a prerequisite for getting social services and before the one outlawing sex toys. That last had been a campaign of one of Perry’s early appointees to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles (no, really).

“Honey, by next week you’ll be across the border, living in beautiful Tulsa, breathing clean air, and attending a decent school,” Alvin told her. “You might even get to study evolution.”

“But I don’t want to go,” Shaniqua said.

There really wasn’t any question about it, though. The final straw was that Shaniqua, now in high school, seemed to like girls better than boys – and that could be a real problem in the godly republic of Perryland.

“You’ll love America,” Gus said. “Just promise me – never root for

the Sooners.”

This story was written by Jeff Prince, with contributions from Betty Brink, Peter Gorman, Eric Griffey, Kristian Lin, Dan McGraw, Bryan Shettig, and Gayle Reaves.