PBS needs to roll back the age appeal of its programming.

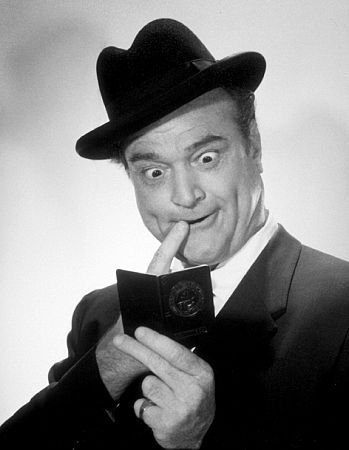

In 1970, radio and television comedian Red Skelton was taken off the air by CBS because his audience was getting too old and younger viewers weren’t watching. That still happens today in the television programming biz, where the younger viewer is far more valued than the older ones.

But that is not the case with public broadcasting. Public Broadcasting Service television stations go hard after the elderly, especially during their pledge drives. Last month, local station KERA even trotted out “The Best of Red Skelton” to get the phones ringing. I don’t know the average age of the Red Skelton fan, but a conservative estimate would put it above 80.

KERA now does four pledge drives a year, meaning that for eight weeks out of 52, shows that viewers have come to expect are temporarily replaced with “special” programs. And for most of the regular viewers under 60, that means clicking to another channel.

KERA now does four pledge drives a year, meaning that for eight weeks out of 52, shows that viewers have come to expect are temporarily replaced with “special” programs. And for most of the regular viewers under 60, that means clicking to another channel.

What KERA aired last month is fairly typical of recent pledge drive programming. Some of them are like self-help infomercials for the aged. Dr. Daniel Amen tells you how to prevent Alzheimer’s disease by using a special brain scan. Dr. Mark Hymen instructs folks on how to keep their brain sharper as they age. Suze Orman details money management for widows. There was even a program that taught yoga to people in their 70s.

Bill Young, KERA’s vice president in charge of programming, admits that “the pledge drive programming does skew a little toward older viewers, but there is a fair amount for younger viewers as well.”

So what did the younger viewers get? Concerts by Paul Simon and Bruce Springsteen, which I would contend are for the middle-agers. Similar demos for an Otis Redding concert from 1967, and ’60s folkies Peter, Paul and Mary.

In effect, the national PBS programming people keep recycling older programs that have been the most successful in bringing in the bucks. Hence, you get a doo-wop music special that was shot in Pittsburgh in 2002 and is still seen around the country four times a year. “In the Still of the Night” by The Five Satins is certainly a nice song, but more than 50 years old. Red Skelton might have liked that number.

KERA aired 26 specialty programs during its March pledge drive. Why not incorporate the popular programs like Antiques Roadshow and the investigative Independent Lens and American Masters profiles into pledge events? Young said that has been tried some in the past, “but historically those programs do not generate a lot of money.”

One result has been that the programming leans heavily on the self-help gurus who are pushing their products and giving KERA a cut via the pledges. It used to be you got a coffee mug or a tote bag if you joined, but now, for a pledge of maybe a couple of hundred dollars, you get a book on how to manage your retirement funds.

In part, this is just the way public broadcasting stations have always done things. Before the advent of cable television and the internet, public television represented an important alternative for viewers. Because it provided news and cultural programming, commercial-free, that was not found on for-profit stations, KERA could argue that “viewers like you” should support the programming directly, through donations.

But that is not the case any more. Public television is no longer the only place you can go to see cooking shows or history programs or even thorough investigative pieces. The pledge programming process is no longer about lauding “experimental” programming or the “originality” the shows provide. It is more about keeping those aging viewers and their money, the people who have been with them since TV was a four-channel universe.

Like many mainstream media institutions, public television has not come to grips with the changing media landscape. Many people in their 20s and 30s don’t read daily newspapers or watch KERA, partly because little is offered that interests them. So the newspapers and public stations are stuck with this older audience, which gets smaller as the years go by, since there is no one to replace them in the pipeline.

About 15 years ago, when I wrote a story on the state of PBS for a national magazine, one of the head honchos in Washington told me, “We have the kids watching us until they are about five or six,” he said, “then we lose them for a long time and get them back when they are in their 40s.”

Maybe we should adjust that number. Viewers now probably return in their 50s. And the average is surely about 10 years older than that during the eight weeks of pledge drives each year.