Texas rural women are battling modern dragons to save some “country” for future generations. A drive through her Wise County stomping grounds with Sharon Wilson is like getting a battlefield tour from a guerrilla commander while the bullets are still zinging overhead.

Texas rural women are battling modern dragons to save some “country” for future generations. A drive through her Wise County stomping grounds with Sharon Wilson is like getting a battlefield tour from a guerrilla commander while the bullets are still zinging overhead.

For Wilson – a.k.a. “Texas Sharon” – the sights, sounds, and smells offer painful reminders of her continuing battle against natural gas drillers and the havoc they wreak in a place she once considered paradise.

She stops on a farm road where a noisy compressor station has been plopped down in a pasture and points to a gravel-covered area beside a creek. For months, oilfield workers had used a portable toilet perched beside the creek. After they left, Wilson went to investigate and was nearly knocked over by the stench. Weeks’ worth of fecal matter had been dumped into a pit beside the creek.

Wilson complained to the Texas Railroad Commission, which refused to test the water. Still, the pit was cleaned up and filled in with gravel a few weeks later.

Another mile down the road is the tree she climbed in icy weather last last winter to get a better angle for photographing a drilling sludge pit. The drillers were using a large hose to drain wastewater from the pit. The hose ran beside the road and underneath a bridge – where it spilled its load into a wide and flowing creek.

Cows drink from the stream. Farmers use it to grow crops. The crops and beef make their way to people’s stomachs.

“The drillers have run amok,” she said.

Farther west, in rural Parker County, Kathy Chruscielski wages a similar fight. She gets much of the credit (or blame, depending on one’s outlook) for spurring creation of the Upper Trinity Groundwater Conservation District, which protects the aquifers supplying rural dwellers with water for their homes. A stay-at-home mom, she went reluctantly to her first public meeting a few years ago to find out who was going to fix the county’s worsening water situation. When she found out the answer was “probably no one,” an activist was born.

Across much of rural Texas, women like Wilson and Chruscielski have taken lead roles in fighting big industry, polluters, municipalities, and lawmakers who threaten their clean and peaceful country living.

Transportation projects, eminent domain abuses, strip mining, nuclear- and coal-fired power plants, and any number of other industrial and big-city pains have traditionally threatened outlying areas that lacked the protections or organized leadership to fight back. That’s changing. Rural dwellers are tapping into technology and grassroots resistance to avoid being bullied, and women are often leading the fight.

“I don’t want to leave this mess for the next generation,” said Terri Hall, a Bexar County resident who led a successful battle against a tollway and related eminent-domain land-grabs that were being planned by the state near her home north of San Antonio. “We keep kicking the can down the road, and nobody ever seems to have the guts or the spine to fix it. And without the people rising up, government doesn’t have the will to fix it themselves.

Water is Kathy Chruscielski’s hot button for good reason: When you’re trying to run a five-person household, a faucet with nothing coming out of it is a major disaster. Worries about what was happening to her water well turned this mother of three, who plays piano at church, enjoys listening to jazz, and cares for a horse named Capalani, into one of rural Parker County’s most avid activists.

The Chruscielskis moved to the Remuda Ranch Estates west of Fort Worth in 1999. Less than three years later their water well petered out. “We first thought it must be some minor equipment failure,” she said.

It wasn’t. The well, her family’s only source of water, was sucking mud. Groundwater supplies were being used up faster than they were being replenished, and their well was no longer deep enough.

“We were shocked,” she said.

Her next shock was discovering the cost to drill a new well – $17,000 to tap into the Trinity aquifer or $6,000 to drill to the shallower but more iffy Paluxy aquifer. Existing wells can’t just be dug deeper: Homeowners must dig new wells hundreds of feet into the ground, and well-diggers can charge $25 to $30 per foot. The family chose the cheaper option, drilled to the Paluxy, and recaptured a water supply, but Chrusckielski couldn’t help but worry about the future.

“I had already felt the pain – when you turn on your faucet and no water comes out, when you can’t flush your toilet, you can’t shower,” she said. “If you don’t have a reliable water supply, your house isn’t worth a dime.”

In the summer of 2006, she heard about residents in nearby Aledo whose water wells were going dry after gas drillers flocked to the area, tapped into the aquifers, and pumped out millions upon millions of gallons of water to use for hydraulic fracturing or “frac” drilling, the process that sends a powerful stream of water, sand, and chemicals deep into the ground to bust up shale and force out natural gas. (Drillers claimed they weren’t taking water from the same aquifers that household water supplies came from, but a county study later showed that was not true in many cases.) The toxic backwash from the gas drilling is then trucked away to injection wells – or at least that’s what is supposed to happen.

A drought in 2006 only exacerbated Chruscielski’s water worries. Then a neighbor’s well went dry. He lived on a hill, meaning a driller would have to dig even farther to reach the aquifer. His bill for a new well into the Trinity aquifer was about $30,000.

In August of that year, Chrusckielski attended a Parker County Commissioners Court meeting to listen to a discussion about water wells sputtering out. It would change her life.

“I’m mostly an at-home mom,” she said. “We knew about this meeting, and my husband said, ‘Are you going?’ and my first reaction was, I’m really busy, and I don’t know if I’m going to make it.”

But she went, just to keep her husband, Ken, from having to take time off from work to attend.

Emotional residents packed the courtroom and described how, when their wells ran dry, they had tried without luck to get help from legislators and state agencies. They discussed the possibility of establishing a groundwater conservation district, which sets rules to protect wells, promote conservation, prevent waste, and manage water usage. But no commitments were made. During the meeting, Chruscielski borrowed a pen and paper from Commissioner Jim Webster and began collecting names.

“I figured, what better time to start a petition than when you’ve got a courtroom full of people,” she said.

Afterward, a WFAA-TV/Channel 8 reporter approached her for an interview.

“The next thing I know, the light came on on their camera,” she said. “I didn’t wear makeup that day. I just wanted to see what was going on. From that day on I became an advocate. I thought there had to be a way to make this situation better, and that’s how PARCHED got started.”

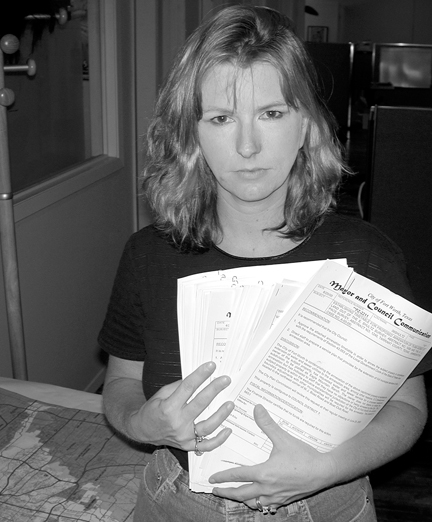

Parker Area Residents Committed to Halting Excessive Drilling (PARCHED), an informal group of about 400 people, is represented most often by Chruscielski at municipal meetings. The group documents environmental mishaps, gives presentations, and distributes an e-mail newsletter keeping rural residents abreast of water issues. And they played a vital role in pushing for an election to create the four-county groundwater district.

Chruscielski’s efforts have prompted supporters to suggest she seek public office, but so far she’s been content to work independently. Rural areas don’t have the same protections as cities, and it takes strong-willed individuals to make stands and shape policies.

“Ironically, I’ve been asked by both parties to run for various offices, but I don’t care for partisan politics. I’m interested in issues,” she said. “These issues aren’t partisan. Everyone should care about having reliable groundwater.”

City dwellers who get their water mostly from big reservoirs might not realize it, but the majority of water consumed by Texans comes from underground aquifers. In Fort Worth, gas drillers account for less than 2 percent of the water used each year. But in Parker County, that percentage is closer to 25 percent, according to an independent 2007 groundwater assessment study.

On a recent afternoon, Chruscielski pulled up to a stop sign at White Settlement Road near her home. Two large wastewater trucks were pulling away from a drilling site across the street, probably on their way to an injection well. The trucks are a constant sight these days for anyone living in rural areas around Fort Worth.

“That’s our water – there it goes,” she said.

After those two trucks left, another one approached from the opposite direction and entered the drill site.

“That’s our water, coming and going,” she said, her voice getting louder.

She turned west and was soon stuck behind one of the slow, lumbering trucks, another common occurrence on the narrow farm roads.

“What’s in that truck? Is it radioactive?” she said. “When they stop you can see water dripping out of them. They say it’s salt water, harmless. You gargle with salt water. You don’t want to gargle with that water.”

Near Aledo, a brown patch of ground beside a road shows where a gas company’s wastewater truck overturned and spilled its load. Farther north, in Wise County, a half-acre of bare dirt scars a pasture once thick with grass. Last summer, the driver of an 80,000-pound water truck pulled to the side of FM 755 after midnight and intentionally emptied his load of drilling waste onto the ground. The chemical-laced liquid flowed down hill into a creek bed that runs underneath the road and into a pond. A nearby homeowner later reported that his water tasted and smelled funny.

Chruscielski’s online newsletters have made her a solid source of information on water levels, droughts, and gas drillers. The demands on her time and energy are fierce, and she feels a kindred spirit in Wilson, who fights against the industry while working a full-time job and raising a child as a single mother. The two women exchange information and keep each other from feeling lonely in their quests.

“Sharon is great,” Chruscielski said. “She’s a little more militant than I am. She’s quite a character.”

Gwen Lachelt, founder and director of Earthworks Oil & Gas Accountability Project (OGAP), has spent the past two decades battling dirty practices by drillers in Colorado and New Mexico. Along the way, she became a central source of information for people across the country. In recent years, she has come to know Wilson and Chruscielski well.

“Those are the two [rural leaders] who come to mind in the Fort Worth area,” she said. “I couldn’t be more thrilled with Sharon and Kathy. It’s been wonderful to work with them. We did some field tours and a round of public meetings in Fort Worth and Weatherford. They are really trying to get the word out and get more people involved.”

In 1988, Lachelt was just like them, living in a rural area, shocked by what drillers were doing to the countryside, and motivated to get involved. Founding OGAP and spurring grassroots troops was a chore.

“We didn’t even have e-mail,” she said. “We completely relied on the phone and snail mail, and we relied on getting people to come together in meetings. This era is just so much better. Now in five minutes you can be on the web and find a document that answers your question, or you can find where to go to find the information. Through the Information Age we’ve set up an incredible network to support people whose lives are affected by oil and gas.”

“We didn’t even have e-mail,” she said. “We completely relied on the phone and snail mail, and we relied on getting people to come together in meetings. This era is just so much better. Now in five minutes you can be on the web and find a document that answers your question, or you can find where to go to find the information. Through the Information Age we’ve set up an incredible network to support people whose lives are affected by oil and gas.”

OGAP’s directors and staff are diverse, but women predominate.

“There is a lot of truth that, for whatever reason, a lot of women have stepped forward and become leaders in the oil and gas movement,” Lachelt said. “I haven’t ever sat down and tried to analyze why. I sort of hesitate to start sounding off on that.”

Mothers, though, are always concerned about impacts on the environment and on their children’s health, she said.

“By and large, people just want oil and gas [companies] to do it right,” she said. “If they are going to come in and drill in our backyards, they really need to pursue every avenue of best practices to reduce their impact. That’s where we come in.”

Texas has a long history of strong-willed women. They’ve owned and worked ranches. They’ve tackled a maze of inequalities in careers, housing, politics, and education and have fought for wildlife conservation. Along the way, they’ve often been criticized, even from within their own ranks, for being overly emotional. But the women who are fighting many of Texas’ rural legal battles describe what fuels them as passion, not “emotion,” particularly about the state’s long-term future.

Terri Hall was so shook up by plans to turn State Hwy. 281 into a toll road near Bulverde in rural Bexar County that she founded the San Antonio Toll Party in 2006 to fight the Texas Department of Transportation. Grassroots resistance, an e-mail campaign, and a couple of lawsuits have prevented the highway department from going through with its plans.

Hall, the mother of seven children including a 3-month old, has led the fight because of those children.

“I really don’t have the time,” she said. “It’s one of these areas that has taken over my life, and I really want my life back. But I don’t want my children to be having to pay off the debt from a bad decision by today’s government.”

Reading reams of legislative proposals, attending meetings, organizing support, and consulting attorneys and various experts while also juggling kids, shopping, and housework – and doing it all for no pay – takes a devoted fighter. And, without doubt, the activists consider themselves in a fight.

“We’re on a warpath to get this changed, and we’ve had to rattle quite a few cages,” Hall said. “No one is paid in our group; it’s all volunteers. We have to do the hard work, the kicking and scratching our way up to the legislature and saying we’re not going to go away until you listen to us.”

Technology simplifies the process, although some rural areas suffer from a lack of internet access. But even that’s changing with the growth of satellite service. “It has certainly connected communities in ways that have not been seen in a long, long time in Texas,” she said.

Rural communities across Texas used the internet to coordinate their fight against the Trans-Texas Corridor, as the huge cross-state tollroad complex was dubbed. Mae Smith, mayor of the tiny town of Holland, helped derail the massive tollroad project that threatened to rip apart farms and ranches from one end of the state to the other, as Fort Worth Weekly reported in a cover story (“Rocks for the Goliath Road,” July 9, 2008). After state transportation officials ignored their concerns, Smith and other activists spotted a provision in a state law that allowed them to form local planning commissions and demand a seat at TxDOT’s table. The inside look at the process helped them spot deficiencies and a lack of required environmental impact studies that allowed them to bring the project to a halt, at least temporarily.

Closer to home and on a smaller stage, Fort Worth’s proposed annexation of 55 square miles of mostly rural property in 2002 similarly prompted Stephanie Pivec to turn from stay-at-home mom to city-hall slayer. Fort Worth officials said the city needed to take in all that property to control growth. Pivec saw it as a land grab designed to boost the city’s tax revenues without providing services in return. She formed the grassroots Citizens Against Forced Annexation, a group of mostly rural homeowners and business operators.

Pivec hammered city officials and city council members and asked for detailed information. When she was denied, she filed open-records requests. When the city tried to bill her $690 for requested materials, she filed a complaint with the attorney general’s office.

In the end, the city reduced the amount of land it sought by involuntary annexations and changed some of its rules about providing services.

Nowadays, Pivec is working full time and doubts she could take on such a responsibility. And she hesitates to generalize about the genders or speculate on why women in rural areas seem to lead so many fights. But when pressed, she said, “Maybe women bring to the table all the PTA stuff: If women are mothers they try to protect their children.”

It’s a sentiment that every woman interviewed for this story mentioned.

“I think women worry about future generations,” Wilson said. “I picture my children and my neighbors’ children, and I worry about what will happen to them.”

Women also benefit from being perceived as underdogs.

“Sometimes when men fight an issue, they are perceived differently than women,” Pivec said. “If a mother goes up to fight a battle to protect her children, that’s a noble battle. It seems like a more noble fight even if the women are saying the same thing as a man.”

Oh, and don’t underestimate the fortitude of a woman willing to live in the country away from city comforts, she said.

“Country girls and city girls are two different animals,” Pivec said. “When you cross the Tarrant County line into Johnson County, it’s a whole new world.”

“Texas Sharon” can attest that Wise County is certainly a whole ‘nother world. For the past few years, Wilson has documented problems with gas drillers, posted damning photos and columns on her Bluedaze web site (txsharon.blogspot.com), and complained to the Railroad Commission, an agency that’s supposed to regulate drillers but often seems more intent on protecting the industry. The agency has to be spoonfed information to prompt even the tamest of reactions, she said.

“Texas Sharon” can attest that Wise County is certainly a whole ‘nother world. For the past few years, Wilson has documented problems with gas drillers, posted damning photos and columns on her Bluedaze web site (txsharon.blogspot.com), and complained to the Railroad Commission, an agency that’s supposed to regulate drillers but often seems more intent on protecting the industry. The agency has to be spoonfed information to prompt even the tamest of reactions, she said.

“I tell them, ‘I’m a mother, and I drive to work and to the grocery store, and I see all these things. Why can’t your inspectors find them?’ “

Taking on government and industry earns detractors as well as supporters.

“Why don’t you raise your kid, tend to housekeeping, and keep your nose out of our business?” is an oft-heard sentiment from the drillers who regularly scour her site and leave comments. Wilson’s been called a commie, socialist, busybody, shrew, left-wing radical – and worse. She first began using the handle “Texas Sharon” on her Bluedaze site because she didn’t want her identity known. Living miles from a city or police department can be unsettling for a single mom who describes herself as “intensely private and recklessly independent.”

She recalls a deputy sheriff who told her to get a handgun because even if she called for help it might take a while to reach her. She took him up on the suggestion and is now a crack shot with her pistol. Still that hardly eased her mind when someone – she suspects Big Oil hired a private investigator to research her background – began posting her personal information online. Her critics have unloaded on her and left vaguely threatening posts on her site, such as the one that vowed to “shut you up Chicago style.”

“They have threatened me,” she said. “They have made fun of me. They have concocted all kinds of stories about me. Those are posted in cyberspace where they will be forever for anyone – including future employers – to see.”

Like many others in rural areas, she doesn’t have home internet service. So she takes her laptop and drives into Decatur most days to use internet service at a local coffee shop, where she writes her e-mails and blogs.

Ironically, the laptop and video camera she uses to document assaults on the countryside were paid for by the drilling industry. She owns half the mineral rights on her property, so when a gas company made plans to drill beneath it, she signed a lease and received a bonus and royalties.

“They were going to drill whether I signed or not,” she said. “If I signed, that meant less money going to them.”

The money helps fund her fight and means she doesn’t have to seek advertisers for her web site. But the enormity of fighting a multi-billion-dollar industry in a state with laws stacked in drillers’ favor can be daunting. On bad days, she reads letters and e-mails from people thanking her for all the work she does on her own nickel.

“I used to think I’m the luckiest person in the world to live out here,” she said. “It looked like something out of Norman Rockwell. I wanted a simple life.”

But the only publications in North Texas that strive consistently to show the downside as well as the benefits of drilling are the Weekly and Denton Record Chronicle, she said, and neither focuses much attention on Wise County, which has the most injection wells of any county in Texas.

Wilson didn’t notice anyone in her neck of the woods trying to keep the industry in line, so she reluctantly stepped forward.

“This is my contribution,” she said. “My neighbors are grateful, but they think I’m going to get killed and found in a ditch. But I believe it is morally wrong to profit off of someone else’s misery. It’s not right that they can put these industrial things next to your home, and then you can’t sell your home, and everything you have is invested in it.”

Wilson’s worries even crowd her subconscious. She recalled a recent dream about one of her neighbor’s children, a tow-headed young boy who has large, beautiful eyes, a beatific smile – and a severe case of asthma. Wilson suspects the diminishing air quality exacerbated by gas drilling emissions is the root of his problem. In her dream, the little neighbor boy was bald and frail and appeared to be dying. She awoke even more committed to spend whatever money and time it takes to document and wage war on environmental atrocities. Still, it’s tough. Lately she’s considered selling her homestead and moving far away from the Barnett Shale play.

“No one in Texas is doing anything to rein in oil and gas, and there is going to be a big price to pay,” she said. “I was talking to my neighbor the other day, and I said, ‘Why am I even doing this?’ But somebody has to do it. I’m articulate, and I can do it. Wise County has nothing or nobody to report on this – there’s just me.”

Most children don’t pay attention to such issues, but the young man who lives with her notices. Her 14-year-old son, Adam, swells with pride when discussing his mother’s activism.

“She’s done a lot,” he said recently. “She used to go over to a well that was really, really dirty, and she got them to clean it up.”

Adam was in the car with his mom in January when she noticed a hose leading from a sludge pit to a creek. She called the sheriff’s department and fire department and then waited on the side of the road for about two hours for someone to respond. A fireman finally showed up and said he had talked to the driller, who insisted that only fresh water was transported in the hose. The driller said he was transferring fresh water from one frac pit to another pit farther down the road to “conserve fresh-water resources” and that the hose was cut and left lying next to the creek because slicing it would “facilitate an easier removal.”

The fireman left. Adam said, “See, Mom, you are overreacting.”

Then the boy learned a life lesson from dear ol’ Mom. See, Wilson wasn’t buying the driller’s explanation or the fireman’s eagerness to believe whatever he was told. What she saw was a hose leading from an oily, mucky pit, down the side of the road, and into a creek. So when she got home she called the Railroad Commission and filed a complaint. An inspector arrived three days later and tested the water, which showed evidence of “congealed oil” and chlorides. The inspector is now seeking enforcement action against the driller for “allowing the un-permitted discharge of oil field mineralized waters, or drilling fluids, into a watercourse or drainageway.”

Three weeks later, Wilson talked to the fireman, who told her that he had caught the driller dumping tainted frac water into the same pit.

“I thought that was pretty awesome,” Adam said. “She’s like a ninja mom.”

A very admirable activist lady! Keep up the good fight.

Meant to say some very admirable activist ladies! Saturday I’m joining others in San Antonio at the San Antonio River Authority to protest fracking. I have gone on a tour around San Antonio. Fracking may be coming very near to where a cousin lives in south San Antonio, an area called Via Coronado. When these frackers leave, I think what happened at Kelly Air Force Base, will probably happen out in the rural areas. Some of these tanks will be left behind with some of the chemicals or some of the poisoned water and it will be years before they clean it up.