Systems and Process in Abstract Art is a different kind of art exhibit. The collaboration between two local art professors, Vincent Falsetta and Ronald Watson, is an un-self-conscious master class in genuine and genuinely idiosyncratic methodologies, a happy blend of quasi-architecture, color theory, and new ideas about process, all with a Futurist bent. Art students are strongly advised to check the show out.

Spread throughout the lower floor of the Fort Worth Central Library, Systems and Process also includes some of the artists’ studies and sketches, pointing up the fact that libraries aren’t just galleries or repositories but places of learning, in case all of the chattering, internet-cruising patrons and shelves of videos had you thinking otherwise. The exhibit shares space with – and issues rebuttals to – items from the library’s permanent collection, including an oil painting of flowers by Mary Apple and Charles T. Williams’ Modernist bronze figurative sculpture, “The Argument.”

Spread throughout the lower floor of the Fort Worth Central Library, Systems and Process also includes some of the artists’ studies and sketches, pointing up the fact that libraries aren’t just galleries or repositories but places of learning, in case all of the chattering, internet-cruising patrons and shelves of videos had you thinking otherwise. The exhibit shares space with – and issues rebuttals to – items from the library’s permanent collection, including an oil painting of flowers by Mary Apple and Charles T. Williams’ Modernist bronze figurative sculpture, “The Argument.”

Falsetta, who teaches at the University of North Texas, and Watson, chair of the Art and Art History Department at Texas Christian University, are the furthest things from hot and trendy. They’re also two very different kinds of artists. Falsetta works in wavy two-dimensional fields of color. Watson produces three-dimensional geometric objects, practicing a kind of plainspoken origami. The only aesthetic position taken here is in favor of personal voice.

Unlike most gallery exhibits, Systems and Process is not about new work – some pieces date back to the mid-1990s, and one goes back to 1975. The goal, once again, is to edutain, not make a profit.

Falsetta takes his cue seemingly from cross-sectioned minerals, replicating their radiating, swirling, vibrant lines by slowly smoothing his knife across colorful impastos. The aquas, lime greens, blues, pinks, oranges, even the variations on black and white – they all pop, perhaps because Falsetta knows how to play hues off one another or because he knows exactly how much paint to use. You’d think that with all of the blending and shading he does, some of his “mineral” pieces would be a little muddy. Every brush of the knife, though, is crystal clear. The paintings – each about as a big as a compact-car door – have an Op-Art quality that is unapologetically dazzling. They keep the viewer’s eye moving and his or her higher thought processes engaged.

The artist’s work, based on what’s on view here, hasn’t always been confident. The inclusion of some of his older pieces lets you see how far he’s come. Entries in his “Sound Wave” series from three decades ago are as uneventful as window blinds. Hints of his “mineral” pieces don’t start coming through until the ’90s. “AF 99-11” (1999) is a canvas of what look like orderly vertical rows of tire tracks over which the artist has placed small geometric shapes – triangles, arcs, quadrants – and, in one instance, a silhouette of a man shaking hands with an upside-down man. A few years ago is when Falsetta seems to have begun combining his sharp eye for color with his love of texture, producing canvases that resemble control monitors, with areas of neutral background juxtaposed with rows or stacks of colorful, square “buttons.” The individual directions and widths of his brushstrokes are as vital to the overall compositions as his color choices.

Falsetta’s studies and notes are neatly displayed in glass cases. The verbiage, written in all caps on index cards, is often endearing. (“Martha liked PT v. much -PT seems beautiful + active e much more active [than] other day.”) The studies could double as trippy-dippy mousepads.

All of Watson’s objets are behind glass, and, like Falsetta’s, they keep your eye moving and your feet locked in place.

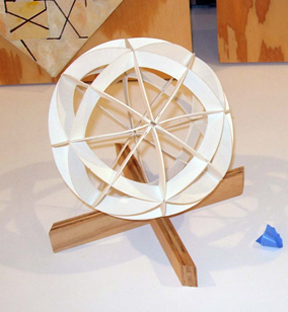

Watson’s materials are simple: just some untreated wood, paper, glue, wire, and occasionally resin. His designs, however, are complex. Snowflake patterns and globes clearly have some kind of psychological grip on him – nothing else explains why anyone not in an insane asylum would spend his free time folding pieces of sturdy paper into triangular braces and assembling them into see-through soccer balls. The average Watson orb is about the size of a cantaloupe. Most are placed in settings. One sits atop a deep-blond wooden labyrinth of sorts. Another crowns a pedestal that resembles a crude mini oil derrick. They all have an otherworldly, alien grandeur, as if they’re totems that had been uncovered during some archeological dig on Mars rather than being created by hand here in this century. Though they probably weigh about two ounces apiece, they’re all pregnant with power.

Watson also does some relief work in wood, gluing together prisms, significantly obtuse angles, and Xs into symmetrical designs. Some are as relatively simple or recognizable as snowflakes, others as dynamic as honeycombs. His lone hanging piece, “Open Passage #22,” is a visual haiku. A precise network of black wires that reminds you of a rake’s “hand” graciously offers up a flat obtuse triangle of polyester resin – with its yellowish tint, subtle cracks, and transparent surface, it could be a chunk of frozen urine. A recommendation: Don’t bother trying to figure out how he made it or, actually, anything else he’s done here. Just enjoy.

Watson’s studies in conté crayon, charcoal, and graphite on paper are on the walls and could stand alone as finished Abstract-Expressionist drawings. Points of cubes branch off into the lines of other cubes and interlock, forming familiar shapes. Crosses and diamonds dominate.

Watson doesn’t contribute any notes. But next to a glass case that contains some of his doodads is wall text that reads “… objects here include some that Watson fabricated or mixed with found objects, only one of which … is not mass-produced. Along with sketches and studies (hanging), they typically are found placed around Watson’s studio as sources of meditation and inspiration.” Which probably explains the unsettling presence of a tiny piece of deadwood that looks like a walking stick topped by a nautilus.

The Fort Worth Central Library clearly is upping its art game, thanks mostly to new employee, artist and former Star-Telegram art critic Janet Tyson, who has curated three previous library shows, most notably a collection of sculptural works from two almost-forgotten Fort Worth masters. She also has tapped gritty found-object imaginist and Fort Worth Weekly contributing photographer Christopher Blay to create an installation piece of library ephemera that will be on view throughout the building starting in August.