There’s not enough brainy art in Cowtown, art that doesn’t require a 10-page artist’s statement to really sing, that makes your heart think, art that seems familiar but is totally alien. Fort Worth isn’t lacking in conceptual art. But most of it is simply theatrical, referential, or overtly political. What we’re missing is art that creates its own aesthetic, that is a kind of poetry but one written entirely in hieroglyphics. Does “brainy” mean “high-tech”? Not at all. Jason Reynaga’s eye-popping tableaux, Matt Clark’s vibrant color fields, and John Holt Smith’s versions of Barnett Newman’s “zips” employ traditional materials and approaches but challenge viewers’ cerebrums — and retinas. Though you might dismiss Reynaga and company’s work as Minimalist or just plain empty, remember that some conceptual art relies on viewers’ tastes and, well, brains to complete it.

There’s not enough brainy art in Cowtown, art that doesn’t require a 10-page artist’s statement to really sing, that makes your heart think, art that seems familiar but is totally alien. Fort Worth isn’t lacking in conceptual art. But most of it is simply theatrical, referential, or overtly political. What we’re missing is art that creates its own aesthetic, that is a kind of poetry but one written entirely in hieroglyphics. Does “brainy” mean “high-tech”? Not at all. Jason Reynaga’s eye-popping tableaux, Matt Clark’s vibrant color fields, and John Holt Smith’s versions of Barnett Newman’s “zips” employ traditional materials and approaches but challenge viewers’ cerebrums — and retinas. Though you might dismiss Reynaga and company’s work as Minimalist or just plain empty, remember that some conceptual art relies on viewers’ tastes and, well, brains to complete it.

One Fort Worthian who tackles Big Issues fearlessly is installation artist and occasional Weekly photographer Christopher Blay. In his first solo show at Gallery 414, Fort Worth’s oldest and most esteemed nonprofit gallery, the founder of the Group f8 photography collective and Thrift Art Gallery Auction, an annual parody of the art world, is socially engaged but not pedantic, brainy but not academic.

In Microaudiotellarevolution, Blay explores the gray area between the truth and technological representations thereof, a continuation of his fascination with a philosopher whose groundbreaking investigations of subject and image have been informing the artist’s work over the past several years. “In his Philosophy of Photography, Vilem Flusser talks about degrees of abstraction from a photograph to the object, suggesting the absence of a true evaluation of the role the machine plays in translation from object to image,” Blay writes in his artist’s statement. “The way I use technology here is counterintuitive to function, and I believe that the circumventing of technological function in this way emphasizes the fallacy of techno-representation.”

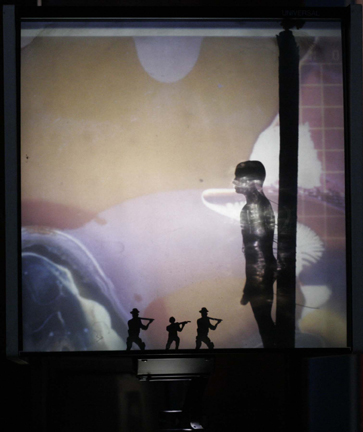

Inspired by the coup in Liberia in 1980, Microaudiotellarevolution is a stark surreality where Death’s scythe is a reporter’s microphone, his hood a shako, and where soldiers die a million silent deaths and soundbites annihilate logic. The first gallery consists of hyper-flat mises en scene of soldiers and prisoners of war in silhouette on microfilm machines. The room is dimly lit to provide contrast and also to set the appropriate, eerie mood. The pieces work as both literal statements and as examples of early abstract-expressionism. The soldiers imply aggression, helplessness, fear. The warped graph paper across which their surely unenviable fates play out creates a fog through which often only amorphous shapes stand out. The entire room is haunted. Even the machines, of the kind you probably haven’t seen in 50 years, seem to long for the scrapheap. The inert yet dynamic space Blay has created has the aloofness of a news report from the gory frontlines and the quiet intimacy of bedtime story written by David Lynch, Jim Morrison, and Colonel Kurtz.

In a side gallery, the viewer unsuspectingly drops into crossfire. Hanging on the wall to his left are several dozen black audio cassette recorders. From each comes the sound of a man talking (or singing incantations). Hanging on the wall to the viewer’s right are headphones. In the middle is a cluster of gas masks with earphones on surrounded by microphones. It’s a press conference in hell.

In another dark gallery is a slide show of Blay as dictator. Wearing black sunglasses and an assortment of military garb, the artist/subject looks off into the distance to suggest visionary concepts, he is caught explaining a point above microphones, his hand on his chest as if totally innocent of some crime, he sits on a sunlit sofa, his hands on his knees, surely awaiting some foreign dignitaries or arms dealers. Blay, an imposing bearded figure, certainly looks the part. The artist is bringing death from a place 99-percent of us have never been to and from a time most of us barely remember to the fore of our sheltered, whitebread psyches.

Microaudiotellarevolution, though subtle, declaims that the deaths of millions of innocents in overseas power struggles don’t just exist in our TV sets.