Heritage counts for a lot in Fort Worth, a town where the Stockyards and the Chisholm Trail, Sundance Square, cowboying, and a Western tradition of friendliness are still parts of the city’s character as much as its world-class museums and some exquisite modern architecture. Not to mention, of course, the spot on the Trinity River bluff where in 1849 the fort was built that gave the city its name.

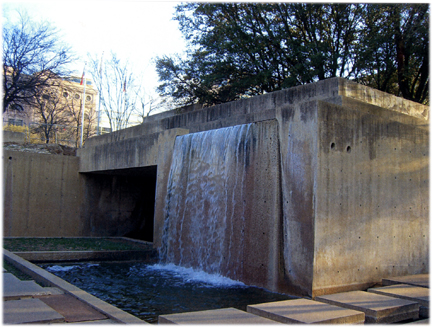

At least that spot, by the historic Tarrant County Courthouse and Paddock Street Viaduct, used to have meaning in Fort Worth. After all, the city went so far as to celebrate that part of its heritage in the 1970s by bringing in a top-notch talent to design a park there. Heritage Plaza was part of it, built to the specifications of landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, with a series of trails, catwalks, overlooks, and water features to tie downtown to the river, all framed within a series of concrete rooms that provided places of peace and quiet beside streets that roared with traffic.

At least that spot, by the historic Tarrant County Courthouse and Paddock Street Viaduct, used to have meaning in Fort Worth. After all, the city went so far as to celebrate that part of its heritage in the 1970s by bringing in a top-notch talent to design a park there. Heritage Plaza was part of it, built to the specifications of landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, with a series of trails, catwalks, overlooks, and water features to tie downtown to the river, all framed within a series of concrete rooms that provided places of peace and quiet beside streets that roared with traffic.

Fort Worth leaders placed a quote on one wall, with water splashing over it: “Embrace the spirit and preserve the freedom which inspired those of vision and courage to shape our heritage,” it said.

About 18 months ago, that wall – and the trash-choked water channels and busted plumbing and other parts of Heritage Plaza – were closed off by the city with a chain-link fence. It was done without public hearings. No city-sponsored studies provided the Fort Worth City Council with options for rehabilitating the plaza and park. Staffers offered no timeline for repairs or reopening.

The city staff simply advised the council in executive session of its plans to close the park. The quirky downtown plaza had been neglected by the city for years, and the complex plumbing system for the waterfalls and miniature canals had deteriorated. City staffers also claimed the walled-off spaces on the bluff had become a draw for homeless people.

But the staff’s strongest talking point was safety. Ever since the four drowning deaths at the Water Gardens three years earlier, Fort Worth has been skittish about parks with water features. Staffers told the council that there was a danger of people falling into the water at Heritage Park – never mind that it’s less than a foot deep in most places. Closing the plaza was the only solution offered.

The city staff based its action on a study done by the engineering firm of Carter & Burgess for the local nonprofit group called Stream and Valleys Inc. The group has a long history of working to preserve the Trinity River basin, including being involved from the beginning with what is now the Trinity River Vision development.

The study painted a grim picture of the park. All of the plumbing and electrical systems would have to be replaced. Safety railings would need to be installed around all the water features. Shifting soils meant some walls would have to be torn down and rebuilt. Better accessibility was needed to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Total cost for all the changes was estimated at $7.3 million.

Few people saw the study, including council members or those serving on the parks advisory board. Adelaide Leavens, executive director for Stream and Valleys, said the organization didn’t set out to keep the 68-page report secret. “Anyone who requested to see it would be allowed,” she said.

The city’s action upset local historians, who would be even more enraged in ensuing months by the Tarrant County College’s destruction of another section of the historic bluff a couple of blocks east of Heritage Plaza.

But in a city so interested in preserving its heritage, city staffers weren’t interested in working with the historians. It took Historic Fort Worth Inc. six months to get records from the city on Heritage Park, and even then the group didn’t get everything they wanted. The city tried to charge the group $7,000 for the records and delayed releasing the information by appealing to the state attorney general’s office.

One piece of information the local historians were seeking was the Carter Burgess study, a PowerPoint version of which was released to them only when the attorney general ruled that it could not be withheld.

And what the historians saw infuriated them further.

“When we saw the PowerPoint, we could tell the decision had been made that the city didn’t want this park any longer,” said Jerre Tracy, executive director of Historic Fort Worth Inc.

Rather than being cherished by the city as an asset, wrote Lisa Lowry, board chairman of the group, “Heritage Park has literally been kept in the dark, as have the citizens of Fort Worth.”

Only in the last few weeks has that attitude begun to change at city hall – and only after the issue of the park’s future was taken out of the hands of the parks department and bumped up to the city manager’s office. Last week, the plaza was placed on the list of “Texas’ Most Endangered Historic Places” by the nonprofit group Preservation Texas. (And last year the Washington-based Cultural Landscape Foundation also placed Heritage Park on its “Marvels of Modernism” list.)

Assistant City Manager Fernando Costa said this week that the city will sponsor a design workshop on Heritage Plaza later in the spring and will study Halprin’s original design alongside safety considerations.

Much of the pressure to rehabilitate Heritage Plaza has come from Ruth Carter Stevenson, daughter of Amon Carter Sr. and one of the driving forces behind the project in the 1960s and 1970s.

“This is a park that celebrates our city’s history, standing on the site where this city was first settled,” Stevenson said. “It is there to remind young people what this city is all about. And when you get some sort of answer from the city as to why they felt forced to close it, the reasons don’t add up.”

If quietly closing a nationally acclaimed and locally significant historic site with nary a word to the public was yet another example of the “Fort Worth Way” of doing business, it wasn’t one that many prominent local citizens, including Stevenson, agreed with. In fact, local historians and landscape architects alike have problems with the study on which the decision was based, as well as the city’s actions.

The Carter & Burgess report is a large-scale full-color presentation with a glossy cover and lots of white space. But engineers based their conclusions on only one day’s assessment at the park, according to the study.

The engineering firm concluded that the plaza’s attraction to “transients and vagrants” was a cause for concern. Certainly the bluff-top portion of the park, with its enclosing concrete walls, tucked next to a busy street, was never easily visible to many visitors or even residents of the city. But statistics from the Fort Worth Police Department show that there have been few reports of problems at the park. Officers were called there five times in 2006, each time on a report of public alcohol consumption. In the nine months of 2007 that the park was open, police recorded nine curfew violations there.

Carter & Burgess’ report suggested that people’s feeling that the park is unsafe was what mattered. “The fact is most city residents refuse to enter the plaza, feeling it to be an unsafe environment, rendering it non-functioning as a thriving urban park,” the study stated. “Some of this fear is more perception than real, but the perception is what counts.”

The engineers recommended demolishing and rebuilding three concrete walls, replacing nearly all the plumbing and pumping systems, redesigning the opening to the plaza, and installing a 42-inch fence around every water feature. Fencing off the water features, the report concluded, was the only way to “meet today’s safety and access codes.”

However, there have been no serious accidents at the park, according to information provided b y the city.

y the city.

Leavens, the Streams and Valleys director, said the study showed the safety issue is critical at the park. “I felt it was important that it was closed for safety concerns,” she said. “We can’t have what happened at the Water Gardens happen again.”

Asked about the shallow water and the park’s lack of a history of injuries, she said, “We didn’t think it could happen at the Water Gardens, either. I would hate for us to wait and make someone a sacrificial lamb before we do something.”

A noted landscape architect who has been asked by the city more recently for his advice on the park rejected the Carter & Burgess plan to put fencing around the water features. Laurie Olin called the idea “completely stupid. People could fall in the Trinity River and drown, but we don’t put a fence around it.”

Lawrence Halprin’s designs have become famous around the world – but they’ve also drawn controversy in many places besides Fort Worth. His works include the FDR Memorial in Washington, Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco, promenades in old sections of Jerusalem, and water parks in many countries.

In Fort Worth, Stevenson and others wanted to celebrate the city’s heritage on the bluff where the first fort was built. Halprin’s design included concrete walls that created “rooms” through which visitors could meander, with water features sometimes at eye level, sometimes underfoot, and sometimes flowing over the walls. He also focused on creating access to the river, a concept the city has embraced in recent years. Stairs and a trail descend from the plaza to the river.

The plaza didn’t provide the usual greenspace of a park. But Halprin wrote in 1972 that there was a “second kind of life in the city” that “seeks quiet and seclusion and privacy This kind of private life has needs for open spaces of a different kind. … It needs enclosure and quiet, removal from crowds, and a quality of calm and relaxation.”

Still, Heritage never satisfied some people’s views of what a park should be. It includes no “wide open spaces,” aside from the views of the Trinity River. Access from Bluff Street has been hindered by increasing automobile traffic. And when the city stopped doing aggressive maintenance, the park deteriorated substantially, and visitors declined as well.

The Carter & Burgess study suggested that Halprin’s design itself presents conflicting messages to park patrons.

“Because of liability issues, many of the public parks in the city that contain fountains, including Heritage Park Plaza, now have warning signs as you enter them declaring to the park user that parts of this park are ‘subject to conditions that might be unsafe at certain times and under certain conditions’ and that you enter at your own risk,” the report said. “Halprin’s design was intent on getting people to interact with the various water features by touching them, splashing in them, and creating a landscape of interaction with the user, not restricting them from interaction out of concern of liability issues. The result is a mixed message to the park user. Ironically, what the park user is being warned of as they enter the Plaza is exactly what Halprin wanted to happen as a main function of the design.”

Other cities have had problems with Halprin parks, which the Carter & Burgess report noted. Aging infrastructure and the reluctance of some city parks departments to spend money on maintenance or restoration have caused some to be demolished. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts demolished a sculpture garden as part of an expansion. Skyline Park in Denver was demolished save for one fountain. Many others have been tweaked.

“Several major cities in the U.S. have been mired in a quandary about what to do with Halprin-designed parks,” the study stated. “Many are of the same age and condition as Heritage. They are all stepchildren of City Parks Departments that have lacked sufficient funds to run and maintain these landscapes. Many are considered outdated and non-functional for their location. All have struggled with the issue of the homeless and safety with the lack of security.”

But another part of the study gives a different view: “Halprin’s design of the plaza is a prime example of his ability to craft a public space and provide a unique experience in landscape art,” it said. “His designs typically include complex water fountains that demonstrate the power and beauty of water in its various forms, utilizing different kinds of movements as at passes through the landscape.”

Halprin has done some redesigns, but probably will not work on this one in Fort Worth. He is now 92 and does not travel, according to Olin. But he does have an opinion on the controversy of his parks.

“A number of my projects have been subject to redesign,” he wrote in a 2005 article published on the American Society of Landscape Architects web site. “Usually, without my involvement in the redesign and rebuilding, the character and quality are changed forever. Some of this is actually being attempted as I write this essay. Usually, this process is not polite. In most cases I feel there is a great loss to the communities for which they were built.”

Some of the Heritage Park redesign decisions will be based on the city’s experience with the Water Gardens. “This [Heritage] is the same kind of challenge we faced with the Water Gardens,” Costa said, speaking of the redesign of the park after the drownings there. “The city worked at great lengths to achieve two goals simultaneously. First we addressed the safety issues. But at the same time we respected the integrity of the park as a masterpiece of landscape architecture.”

Some of the Heritage Park redesign decisions will be based on the city’s experience with the Water Gardens. “This [Heritage] is the same kind of challenge we faced with the Water Gardens,” Costa said, speaking of the redesign of the park after the drownings there. “The city worked at great lengths to achieve two goals simultaneously. First we addressed the safety issues. But at the same time we respected the integrity of the park as a masterpiece of landscape architecture.”

“It is important for us to understand how the original design theme might be adapted to current circumstances,” Costa said. “We need to generate new ideas and explore a wider range of options and build a consensus.”

Costa said that Olin, who will be brought in to consult, is best known for his redesign of current parks, from updating the grounds around the Washington Monument for security reasons after the 9-11 attacks to updating Bryant Park in New York.

Reached at his office, Olin said he has “never set foot in Heritage Park” but will spend the coming months doing research. His location in Philadelphia could benefit Fort Worth. He is a visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and Halprin’s archives are stored at the school.

“I will do research on what [Halprin] was trying to do, and I plan on talking with him,” Olin said. “He is an important figure in landscape architecture, and we need to preserve some of his design. We need to meet with people in Fort Worth and determine what works and what doesn’t.”

“And we need to get the city’s commitment to providing maintenance,” Olin said. “That can be fatal for these types of parks, and we can see that was a problem here in the last 10 years or so.”

Charles Birnbaum, the founder and president of the Cultural Landscape Foundation, first visited Heritage Park about eight years ago. “Every time I go back it gets more and more depressing,” he said. “It’s been 33 years since the bicentennial, and many cities across the country commemorated the event with parks. Halprin’s park in Fort Worth was one of the best designs from this period, and the city allowed this to happen. It is very sad.”

Another factor that could influence the city’s decisions on Heritage Plaza is its possible listing on National Register for Historic Places. Historic Fort Worth Inc. has pushed for the plaza’s inclusion on the register. Generally, sites must be 50 years old to make that list, but there are exceptions. The Texas Historical Commission ruled in December that Heritage Plaza qualifies because it is “at the national level of significance” and “widely recognized as a work of exceptional significance in modernist landscape design.” The designation will be formally applied for later this year, with the state historic commission making the decision.

Another factor that could influence the city’s decisions on Heritage Plaza is its possible listing on National Register for Historic Places. Historic Fort Worth Inc. has pushed for the plaza’s inclusion on the register. Generally, sites must be 50 years old to make that list, but there are exceptions. The Texas Historical Commission ruled in December that Heritage Plaza qualifies because it is “at the national level of significance” and “widely recognized as a work of exceptional significance in modernist landscape design.” The designation will be formally applied for later this year, with the state historic commission making the decision.

In ruling that Heritage Plaza qualifies for the register, the commission wrote that the park “retains a high degree of its physical integrity despite deferred maintenance and its recent closure to the public.”

“The park is still very solid, and it is still a pretty impressive site with national significance,” said Greg Smith, national register coordinator for the Texas Historical Commission. Smith said a listing on the register could affect some design changes, as there are national guidelines that work to “preserve historic integrity.” The city “could address some of the safety issues, but we would feel fencing off the water features would seriously affect the integrity of the original design,” he said.

But neither the Texas Historical Commission and federal agencies have any authority over design changes – or even the park’s continued existence – even if it gets the historic designation. “We can give an opinion, we can provide advice, but if the city’s decision was to bulldoze it, then the only thing we would do is take them off the list,” said Rachel Leibowitz, a historian with the Texas Historical Commission. “We are in an advisory capacity and assist in helping to make the best decision possible.”

Ruth Carter Stevenson sees the restoration of Heritage Park as “vital for this city.”

“Parks need to be maintained for the public, and there is a cost to that,” she said. “At some point, the city decided that the cost to keep this park open to the public was too much. That is just the wrong way of thinking. It is not the way city government should be working for the people of this city.

“They have closed a city park that was done by a man who is known as one of the most acclaimed landscape architects in the country, and the city has never explained why they closed it,” she said. “This has all been handled so poorly by the city. It’s as if the people in city hall don’t care about the people in Fort Worth.”

Costa, the assistant city manager, acknowledged that the park closing should have been done more in a more public manner. “It makes sense ordinarily to be forthcoming, to give better decision-making ability to the public,” he said.