John Frum and Ray Liberio have been playing music, together and apart, since Liberio showed up at a Haltom City house party to offer his talents as a 16-year-old bass player to Frum’s high school band. Not long after that, they began recording their music as well. But it wasn’t until they hit their 30s, after years of playing in well-known and not-so-well-known bands in North Texas, not until Frum had moved away to Seattle and ended up with some Microsoft cash, that their thinking made a logical leap. Frum moved, finally, from “let’s start a band” to “let’s start a record label.”

He wanted to save his music – and that of other bands he’d known and played with – for their fans and friends, if not for posterity, and to spread the word of it as far as they could. So three years ago – the next step from making records at home and selling CDs out of the car trunk – he created Indian Casino Records as a “back pocket” music label. The first release: a CD by Liberio’s band The Me-Thinks, also utilizing Liberio’s talents as a graphic designer. And if the label is located in Seattle, no problem: Their old Haltom City crew is still the nucleus of what they do. Just think of it as the Southwest-Northwest Passage, musically speaking.

Independent labels have always played a role in establishing new directions in music – from Atlantic Records, which created rhythm & blues as a musical genre in the ’50s, to Seattle-based Sub Pop Records, which lit the fuse that set off the “grunge” explosion in the ’90s. But the importance of indie labels is on the rise these days, in an environment where you can make a record in your living room and where technological changes have eroded major labels’ dominance of the music industry.

Indian Casino and its work are also a sign of the times in other ways: There are no strict delineations of genres, either by the label or the musicians involved, who are continually forming side projects to mingle influences and musos in new ways. Nor is geography a defining element. For those involved, travel is an assumed part of their lives: Making an album by Texas musicians, on a label based in Washington state, to sell all over the world via downloads and internet sites, doesn’t seem all that strange to them. Whether it’s cowpunk from Fort Worth-based Barrel Delux, Frum playing garage psychedelia with a Seattle friend, or a customer in Japan downloading a side-project album from a member of Cowtown’s Theater Fire, it’s all one world, baby.

Frum, a software programmer, and Liberio, a graphic designer, are the classic boys who never grew up. Both spent their wonder years in and around Fort Worth, and most of those years involved music.

Frum was born in West Virginia and lived in Ohio before moving to Fort Worth when he was 13. A year before that, his stepdad had adopted him, and the kid had a chance at a last name other than the one – Himelrick – on his birth certificate. As fate would have it, his stepdad’s surname was the same as the one attributed to a mythical World War II G.I. worshipped by cargo cultists on the South Pacific island of Tanna. As Frum likes to say, “I was adopted into mythology.”

As a child, Frum would thumb through his mother’s record collection and ask her to spin his favorites. As a teenager, his obsession with music was fed by hearing the punk rock songs his buddy Vinny Pimentel taped off Dallas station KNON 89.3 FM. Eventually, he persuaded his stepfather to buy him a set of pawnshop drums and started jamming in friends’ bedrooms and garages. When Frum’s band, Jon Doe, was looking for a bass player, Liberio came calling.

Liberio was born in Rochester, N.Y., and moved to the Eagle Mountain Lake area when he was eight. He’d shown an interest in music as early as age three, when he put tooth marks in every key on his mother’s piano. In Texas, he learned guitar from a slightly older kid named Michael Bandy and was mentored by his neighbors Brian and Eric Gallagher, who had a band called Naked Picnic as well as their own practice space, complete with a makeshift stage and a refrigerator full of beer.

Haltom had hangouts like the “Freak Palace” – really the garage of an aspiring drummer whose corporate executive mother frequently traveled, leaving her son and his cohort with a place to jam. The places reminded Liberio of the Gallagher brothers’ warehouse, and he signed on with Jon Doe. The teenage musos received some early validation when KNON played a song from a demo tape they’d recorded, with borrowed money, at a studio in Dallas.

When the wheels inevitably came off Jon Doe, Frum and Liberio played in a succession of bands, together and separately. With a couple of exceptions – Frum played in an early lineup of Dallas punk crew Hagfish, while Liberio was the original bassist with misogynistic rap-rockers Pimpadelic – their bandmates were drawn from a revolving cast of Haltom City friends. At each step along the way, they documented their efforts with homemade or studio recordings. Over the years, Frum and Liberio both became proficient on guitar, bass, and drums, as well as singing and songwriting. Their late-’90s outfit, Hasslehorse, was among the first bands to play at the late, lamented Wreck Room, and “On the Mend,” a song from the band’s self-released 1997 CD The Chicken Factory, even got some airplay on KEGL 97.1 FM “The Eagle.”

When the wheels inevitably came off Jon Doe, Frum and Liberio played in a succession of bands, together and separately. With a couple of exceptions – Frum played in an early lineup of Dallas punk crew Hagfish, while Liberio was the original bassist with misogynistic rap-rockers Pimpadelic – their bandmates were drawn from a revolving cast of Haltom City friends. At each step along the way, they documented their efforts with homemade or studio recordings. Over the years, Frum and Liberio both became proficient on guitar, bass, and drums, as well as singing and songwriting. Their late-’90s outfit, Hasslehorse, was among the first bands to play at the late, lamented Wreck Room, and “On the Mend,” a song from the band’s self-released 1997 CD The Chicken Factory, even got some airplay on KEGL 97.1 FM “The Eagle.”

Besides playing music, the teenage Frum also developed a talent for writing computer programs. In 1997, when he was 25, he got tired of his exciting day job of building displays for Camel cigarettes and started taking computer courses at the then-Tarrant County Junior College. Liberio was working for a company that built flight simulators and got Frum an interview there. That started him on his software career, and in 2000 Frum moved to Seattle to work for Microsoft.

Liberio had graduated from the Art Institute of Dallas and stayed in North Texas, working as a graphic designer for Thomson Reuters, an international finance, news, and technology conglomerate. On the side, he became well known for designing concert posters for Cowtown bands and venues.

Before Frum made his move to the Northwest, he and Liberio had been meeting up once a week with a couple of other musicians to write and record songs. After Frum’s departure, that group evolved into The Me-Thinks, who created an elaborate mythology around their party-hearty lifestyle and the Haltom City warehouse where they practiced. And those were some of the seeds Frum took with him to his new gig.

In Seattle, Frum set up a basement studio, dubbed the Snakepit. He put it to good use on Liberio’s annual visits to the Northwest, when they’d drink a little of Frum’s homebrew and make a little music. They co-wrote one song called “Murder and Sushi” after witnessing a slaying outside a Japanese restaurant, but that and some other early tracks were lost in various computer crashes. (For one visit, they obtained a Breathalyzer to monitor their level of inebriation during the recording sessions.)

Frum also played with Seattle area musicians and kept up his friendships with other musicians back in Texas. In 2005, he grew tired of the corporate culture at Microsoft (which, over time, had left him wracked with anxiety and insomnia) and left the software giant to work freelance. He took some stock options with him, and with money in hand, decided a record label would give him a way to stay in touch with the rambunctious crew he’d been playing with since high school and help them to get their music heard.

Liberio’s art background made him the logical choice to create the label’s look and feel. Artwork from Pussyhouse Propaganda, Liberio and co-conspirator Calvin Abucejo’s “art crimes” company, adorns most of the Indian Casino catalog. (The duo garnered “best graphic/web designer” honors in Fort Worth Weekly’s “Best of 2008” issue.)

But there are Seattle connections too. What better name for a Frum-Liberio duo, for instance, than The Pungent Sound? That’s the name they picked for their Snakepit collaborations, which they finally resolved to complete last summer. Late last year, Indian Casino released November of the Beast, seven tracks worth of The Pungent Sound’s hallucinatory garage rock with Frum on guitar, backing vocals and “electronic noises” and Liberio on lead vocals, bass, and drums.

“Running a small label is trial and mostly error,” said Frum, on the phone from Seattle. While he’s an avowed slacker, his 20 years of performing and recording have given him some insights to share with aspiring musicians – starting with “know what you want.”

“I’m happy to write songs and record them in my basement,” he said. “The Me-Thinks are content to play a show every few months. Eyes, Wings and Many Other Things [another Indian Casino group] would like world domination. … If you want to make it, make sure everyone in the band is putting effort behind not just the music, but [the business] end of things. Some bands think that if they get on a little label, the hard work is done. Wrong! That’s when the real work starts.”

In the last three years, Indian Casino has released records for The Me-Thinks and their “brother band” Barrel Delux, not to mention Frum’s own work and music by Eyes, Wings and Many Other Things, a side project of Theater Fire member and former Frum co-worker Sean French. All the label’s releases are available on the company’s web site (indiancasinorecords.com), on Amazon and CD Baby, and via digital download through iTunes and Rhapsody.

“I’ve actually sold a few discs to people in Spain and Japan,” said Frum. Their releases include The Me-Thinks Present The Make Mine A Double EP, a full-length CD’s worth of tunes quixotically spread over two discs. Another of their albums is Coat Hanger Antenna, an EP of twisted Americana from Barrel Delux. Frum, with Seattle multi-instrumentalist Jimmy Andrews, recorded Plantation To Your Youth under the name Transient Songs. Tonsils, Toes and Everyone Knows is by Sean French’s group.

While Barrel Delux recorded two-thirds of its EP with producer Bart Rose at Fort Worth Sound, most of the Indian Casino catalog was recorded in home studios. Either way, Frum believes that mastering – the process of transferring the mixed recording to a storage medium from which copies will be made – is crucial.

“Mastering is not mixing,” he said. “Different speakers, software, and often different environments are used. Ideally you are tweaking the equalization. Often, people apply a lot of compression to make the mix louder, but doing that to extremes fatigues the [listener’s] ears. If you’re recording, it is way more important to get a good recording than to get a loud one … if you want that loud, in-your-face sound, the mastering engineer will oblige.”

The label boss is an old-school music aficionado who believes that the tactile experience of handling a shiny silver disc (or a black vinyl record) brings the listener “closer to the music.” However, he realizes that the way listeners interact with music has changed drastically since he was a teenager. “We’re at a real transformative time with the advent of [online download sites],” he said. “Convenience has trumped everything.” Downloads of Plantation To Your Youth, Indian Casino’s most successful release to date, have far outpaced CD sales, for example. Still, he sees value in doing small runs – 100 or 200 discs – if for no other reason than to send them to reviewers, because “that is still the way reviewers expect to digest new releases.”

The Me-Thinks’ double EP was lauded by the Australian I-94 Bar webzine. “Charge your glass often enough and this band could be your life,” the reviewer wrote. The album contains the hometown anthem “God Bless Haltom City,” which holds the distinction of being Indian Casino’s top-selling single download. Another track, “Burnout Timeline,” is a nostalgic look back at the salad days of the Loco Gringos (a hard-rockin’ ’80s Dallas band whose combination of inebriated good humor and self-effacing shtick was a formative influence on The Me-Thinks) and the Dog Star (a ’90s Berry Street dive whose “Haltom City Nights” showcased the future Me-Thinks in their early incarnations as Hasslehorse, Whizbang, and Guy 2000). “That disc almost bankrupted the label before we got started,” said Frum. “It was idiotic of me to drop three grand on the notion of a double EP, but it was just too funny to not do it.”

Plantation is Frum’s rumination on the passing of a devil-may-care extended adolescence. The music is lushly melodic pop-rock, floating on a dense cloud of ringing guitars. To promote the CD, Frum hired a publicist. “When you hire publicity,” Frum said, “you aren’t just hiring someone to send out the discs, you are paying for their contacts. [And] I don’t just mean magazines and web sites, because often people freelance for different sites and publications.” Even though Transient Songs’ release was reviewed mostly by music blogs originating in the Pacific Northwest, that helped to boost the album.

Plantation is Frum’s rumination on the passing of a devil-may-care extended adolescence. The music is lushly melodic pop-rock, floating on a dense cloud of ringing guitars. To promote the CD, Frum hired a publicist. “When you hire publicity,” Frum said, “you aren’t just hiring someone to send out the discs, you are paying for their contacts. [And] I don’t just mean magazines and web sites, because often people freelance for different sites and publications.” Even though Transient Songs’ release was reviewed mostly by music blogs originating in the Pacific Northwest, that helped to boost the album.

While Frum acknowledges the need for bands to have an online presence, such as a web site or MySpace page, he also sees the influence that reviews in magazines, online blogs, and music sites have on sales, even when those outlets “vary greatly in popularity and journalistic prowess.” His experience publicizing Transient Songs was revealing. “I found out lots of people don’t like reviewing EPs and lots of people don’t want to review you if you’re not touring,” he said. A writer from the Village Voice “liked the release and pitched it to them, but I’m not touring, so no big review.”

For bands that can’t afford the expense of a publicist, Frum recommends calling or e-mailing magazines, blogs, and web sites to find out where to submit releases. “Read reviews of bands you think your style is similar to, and see who reviewed them.” To track the success of a campaign, web-savvy musos can set up search engine alerts with their band’s name, so they’re notified each time an engine indexes a new page where that name appears. College radio stations are listed online, but, he cautions, “be savvy – send [your CD] to the right DJs and shows.” It’s difficult to get distributors to take independent label product (let alone getting them to sell it or pay for it); Frum sees more utility in finding a local shop that will sell on consignment.

Pungent Sound is well named. On November of the Beast, Frum’s multi-tracked, fuzz-drenched, feedback-oozing guitars create layers of sonic murk, from beneath which Liberio’s voice – itself a powerful instrument that can roar, rasp, and sneer with the best of them – declaims lyrics that alternate mystical mumbo-jumbo with dissolute desperation. “Abra-Melin” boasts some of the catchiest heavy rifferama this side of the Queens of the Stone Age, while “Good Morning Duchesse” describes a run-in Frum and Liberio had with Duchesse de Bourgogne Belgian ale. (“Sitting on the stoop just getting stupid / Waiting for my liver to explode.”) The title track’s stately minor key melody, organ washes (which tyro keyboardist Liberio overdubbed one chord at a time, so he wouldn’t have to change hand positions) and white-hot fuzz guitars conjure the shade of late ’60s heavy psychedelic outfits like Houston’s Fever Tree.

The disc was mastered by Seattle-based Soundgarden/Melvins producer Chris Hanszek, who’s done the honors on all of Indian Casino’s releases to date. The duo favors medium tempos that some listeners might find evocative of Seattle’s grunge heyday, but Liberio shrugged off any attempt to find a “Seattle-Haltom City connection” in their sound. “There’s lots of Butthole Surfers [influence] on that EP,” he said. Seeing the Austin-based Surfers unleashing their particularly unhinged brand of LSD-fueled dementia on late ’80s Deep Ellum audiences made a profound and lasting impression on the young Liberio. “The ‘Seattle connection’ is that that’s where John lives and that’s where we recorded. But we could have done it anywhere.”

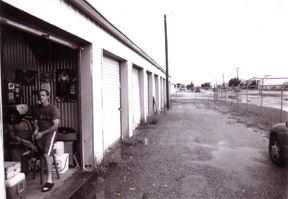

Barrel Delux is probably the most mainstream-sounding Indian Casino act. Their country-rock sound draws on the “cowpunk” or “y’allternative” threads from the ’80s indie rock tapestry. Coat Hanger Antenna’s cover artwork includes interior and exterior photographs of Warehouse 58, the rehearsal space that The Me-Thinks and Barrel Delux shared for over a decade. Both bands reluctantly abandoned Number 58 after all of their equipment was stolen in an April 2007 burglary. (The warehouse was subsequently destroyed by fire in October 2008.) The band’s lineup includes a couple of former Hasslehorse musicians – Frum’s high school buddy Vinny Pimentel on guitar and vocals, and bassist Ratsamy Pathammavong – as well as Liberio’s Eagle Mountain guitar tutor, Michael Bandy.

Bandy, who fronted the bands DragWorms and Tractor Trailer in the ’80s and ’90s, made an earlier foray into documenting the Haltom City crew’s music, releasing the HellDamnCrap compilation in 2002. The CD included tracks by The Me-Thinks, the Ruby Doos, the Wimps (featuring Liberio’s Eagle Mountain Lake inspiration, Brian Gallagher), and Apartment Threading (a Frum nom de disque) alongside better-known bands like Eleven Hundred Springs and Vena Cava (the future Theater Fire). However, HellDamnCrap’s release predated the existence of the online outlets that are Indian Casino’s bread and butter, and thus its notoriety remains purely local.

In contrast to the rest of the Indian Casino catalog, Eyes, Wings and Many Other Things’ CD features a lazy, somnolent lo-fi sound and an opium dream-like vibe, with vocals that alternately sound like a Native American shaman and a voice from the bottom of a well. Frum said that the disc wasn’t picked up by all of his online outlets because it included a cover of “China Gates,” the theme from a 1957 Samuel Fuller war flick, sung on the soundtrack by bit-part player Nat “King” Cole and later recorded by avant-jazz spaceman Sun Ra – even though the band had paperwork proving they’d paid licensing fees for the song.

The label plans to release a CD by Seattle power poppers Dapper Jones later this year. Other than that, Frum said, “I would love to put out some vinyl, but it’s costly.” Indeed, the next item on Indian Casino’s release schedule is a split 7-inch vinyl single by The Me-Thinks and Weatherford-based rockers One Fingered Fist, with whom they share a drummer and an enthusiasm for loud and fast rock. The Me-Thinks are picking up the tab for this one. “We’ve been saving up our gig money for a year,” Liberio said, “so we can put this record out and pay John back for the double EP.”

For Indian Casino’s impresario, it’s more important to document his and his friends’ musical efforts than it is to turn a profit, which explains the origin of the label’s curious name.

“There are a lot of casinos on reservations out here in Washington,” said Frum. “The people going there know they are just going to lose their shirts, but they go for the entertainment. Going into this [venture], I knew I would never make a dollar of profit, but doing it for fun seemed appropriate. Still, I wouldn’t mind having that breakout song or band come from the label, so I could afford to put out and push more music.”

Perhaps Indian Casino is also Frum’s homage to his namesake. Back on Tanna, Feb. 15 is John Frum Day. An article in the February 2006 issue of Smithsonian magazine quotes a village elder: “John promised he’ll bring planeloads and shiploads of cargo to us from America if we pray to him. Radios, TVs, trucks, boats, watches, iceboxes, medicine, Coca-Cola, and many other wonderful things.”

Including, maybe, Texas music via a Seattle company.