Everyone’s calling The Wrestler a comeback vehicle for Mickey Rourke, but he hasn’t really been away. He has worked steadily in this decade, and younger viewers probably know him as the deep-voiced, muscle-bound character actor from Sin City. Ah, but they don’t remember when he first broke into public notoriety in the 1980s, and if they watched Diner, The Pope of Greenwich Village, or 9 1/2 Weeks, they might be stunned at how pretty he was. His smooth, mischievous presence made him catnip to women who liked their men – or at least their male movie stars – dangerous.

Of course, the danger was no act with Rourke, who had a string of offscreen run-ins with the law and then temporarily walked away from Hollywood for a professional boxing career that ruined his face, an act of self-immolation for a sexy movie star if there ever was one.

All this is prelude to The Wrestler, which has resonated in ways unlike other recent Rourke films like Domino or Man on Fire. That’s because this movie is better, but also because its story matches what we know about this actor’s life. The role of a guy who’s lost himself chasing his past youthful glory brings out an anguished, tormented side of Rourke that he hasn’t shown in his supporting performances. This Oscar-nominated performance is a major reason the movie is so powerfully sad.

All this is prelude to The Wrestler, which has resonated in ways unlike other recent Rourke films like Domino or Man on Fire. That’s because this movie is better, but also because its story matches what we know about this actor’s life. The role of a guy who’s lost himself chasing his past youthful glory brings out an anguished, tormented side of Rourke that he hasn’t shown in his supporting performances. This Oscar-nominated performance is a major reason the movie is so powerfully sad.

Rourke plays Robin Radzinski, who prefers to be known by his wrestling name of Randy “The Ram” Robinson. A 1980s star who was famous enough to have his own video game, Randy now lives out of a New Jersey trailer that he has trouble paying the rent on. He still wrestles for small crowds, but the gigs don’t pay him enough money, so he works during the week unloading trucks at a supermarket.

Darren Aronofsky is the director, though you wouldn’t guess that this film is by the same guy who did Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain. All the flashy editing tricks and expressionistic lighting and special effects from those movies are gone, replaced here by unvarnished realism. This is the work of a director showing us that he doesn’t need bells and whistles to tell a good story. The movie uses long tracking shots to simply follow Randy around as he goes through his life’s routines.

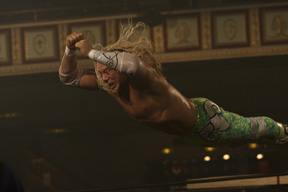

At the beginning, Randy is an impressive sight stripped to the waist and piled up with muscles, but then he gets up and starts walking with an old man’s stooped-over gait, and we notice him wearing a hearing aid. Pro wrestling is a fake sport, but the athleticism required to do the flying leaps and kicks is quite real, as is the wear and tear on wrestlers’ bodies. The film unflinchingly shows what it takes to impress the fans – at one match, Randy is impaled on barbed wire, dropped 15 feet onto a collapsing table, and punctured repeatedly with a staple gun. After seeing this, you won’t be surprised to learn that many pro wrestlers die young.

Every detail of Randy’s world sings: the tacky venues trying to look glamorous, the gap between the wrestlers’ costumed identities and their offstage lives, the sparsely attended “legend” autograph signings. We learn that wrestling is not only grueling but expensive, as we see Randy scraping cash together for steroids, painkillers, and even hair appointments to keep his graying mane its former shade of platinum blond. Real-life wrestlers portray Randy’s fellow combatants, and they bring with them a great sense of camaraderie that adds immeasurably to the movie’s atmosphere.

Randy eventually tries to break free of his emotionally desolate life after suffering a heart attack and being ordered to give up wrestling. He reaches out to an aging stripper (Marisa Tomei, also excellent and Oscar-nominated) and to his angry, estranged daughter Stephanie (Evan Rachel Wood). The script by Robert D. Siegel – a former editor-in-chief of The Onion, interestingly – makes no excuses for Randy and doesn’t turn him into a martyr. Randy’s lot in life is largely of his own making, and an unfathomable piece of stupidity causes him to blow his best chance to reconcile with Stephanie.

Yet you can’t disengage from this self-described “old, broken-down piece of meat” whose hulking appearance jars with his wry, self-deprecating humor. Rourke taps into the character’s theatrical streak in some scenes, like when Randy interacts with a string of customers at the supermarket’s deli. However, the actor also knows when to underplay, as in a scene by the shore with Stephanie, when Randy begs his daughter’s forgiveness. The wrong actor would milk the scene for every drop of pathos, but Rourke exercises restraint, tears flowing from his eyes but his voice staying even, which is what makes the scene so potent. Even more devastating is Randy’s climactic speech to a bloodthirsty crowd, as he risks his life for one final bout with an old nemesis. As he thanks the fans, he reveals the scary emptiness of a performer who’s happy only when he’s being applauded. It’ll make you want to put your head in your hands. The Wrestler ends with Randy’s last flying leap, possibly into his grave, and it leaves you out of breath with the overwhelming force of its tragic story.