Thought reactors were anachronisms? So did some concerned Glen Rose folks.

By BETTY BRINK

Editor’s note: The writer is a former member of a Comanche Peak opposition group, from which she resigned in the late 1980s.

For almost two decades, folks opposed to splitting atoms to turn on a light bulb have been comforted by nuclear power’s fall from favor as an electric-generating fuel. In 1993, one of the last reactors to come on line in this country was Comanche Peak Unit 2, located about 45 miles southwest of Fort Worth in Somervell County. Its twin, Unit 1, went into operation in 1990. With no new reactor orders from utilities since then, commercial nukes seemed to be headed for extinction as surely as the dinosaurs that roamed the county millions of years ago.

For almost two decades, folks opposed to splitting atoms to turn on a light bulb have been comforted by nuclear power’s fall from favor as an electric-generating fuel. In 1993, one of the last reactors to come on line in this country was Comanche Peak Unit 2, located about 45 miles southwest of Fort Worth in Somervell County. Its twin, Unit 1, went into operation in 1990. With no new reactor orders from utilities since then, commercial nukes seemed to be headed for extinction as surely as the dinosaurs that roamed the county millions of years ago.

“Were we ever wrong,” said Debbie Harper, with a wry laugh.

She lives in Glen Rose, five miles south of the plant, and is one of the few locals less than enthralled with the neighborhood nuke whose massive concrete domes seem so jarringly out of place among the scrub cedars, limestone mesas, and hardscrabble farmland. But now, if the new owner of the old plant has its way, those weathered gray domes will be joined by two of even greater capacity. In September, Luminant Generation formally applied to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission for a license to add two new reactors to the site, more than doubling the plant’s electrical output as well as its growing stockpile of highly radioactive nuclear waste.

“I knew there was a nuclear plant nearby when we moved here 10 years ago,” said Harper, an outspoken advocate of renewable energy sources, which she promotes on her political blog, The Somervell County Salon. “But I thought it would soon be decommissioned and that nuclear, as a power source, was pretty much dead. It’s just too expensive, unsafe, and unnecessary.”

That’s why Harper was caught off guard last June, along with most anti-nuke activists around the state, when Luminant announced plans to expand Comanche Peak at an estimated cost of $20.4 billion. There is, however, a caveat to the utility’s grand plan: The Mitsubishi-designed reactors it has ordered have not been approved by the NRC for use in this country and have not been tested under real-world conditions anywhere, a fact that makes Harper even more nervous.

“What?” she asked. “Are they going to test them on us?”

The NRC assured local residents at a meeting earlier this month in Glen Rose that the reactors wouldn’t be approved without a thorough safety analysis. Mitch Lucas, Luminant’s vice-president of nuclear affairs, said the company is satisfied the reactors are “completely safe.”

Still, the proof of the pudding will arrive only when the plant actually comes on line, longtime nuclear power opponent Lon Burnam pointed out. “If that happens, the people of Somervell County will be the guinea pigs for this new generation of reactors,” he said. “That’s why we have to stop this before it gets off the ground.”

Burnam, a six-term state representative from Fort Worth, will be the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit being planned by a coalition of public interest groups. He is no stranger to such fights. Burnam was a Fort Worth intervener more than 20 years ago in the licensing hearings for the first Comanche Peak reactors, working closely with Juanita Ellis, the tenacious Dallas housewife who became a legend for uncovering such momentous design and construction flaws that then-owner Texas Utilities was ordered by the NRC to redesign and rebuild major portions of the plant, even though it was almost 90 percent finished. Even more humiliating, the utility’s CEO was forced to make a public apology for the company’s massive construction failures. By the time electricity finally began to flow from both units, Comanche Peak had taken 19 years to build and cost $11 billion. It was 10 years overdue and $9 billion over budget, but it was undoubtedly a safer plant.

The battle this time, however, is shaping up differently.

For one thing, environmentalists, many of them veterans of the first battle of Comanche Peak, will have evidence of actual, rather than just theoretical, health effects in the area around the plant: Cancer rates in Hood County, Somervell’s nearest downwind neighbor, have increased significantly since the plant came on line. And other issues will be in play that weren’t germane last time around – like water. In a drought-damaged area of Texas with predictions of more drought to come, the plant’s voracious thirst for water is high on the list of objections.

“We can live without a lot of things,” Harper said. “But we can’t live without water.”

The Comanche Peak plant was built along the banks of Squaw Creek, once a meandering and sometimes shallow tributary of the Brazos River. Squaw Creek was dammed almost 20 years ago to provide a reservoir of cooling water for the plant and as a discharge site for its low-level radioactive wastewater. Those waters leave the plant at temperatures of around 113 degrees, eventually winding up in the Brazos, the longest river in Texas and one of the most magnificent, flowing 840 miles from its origins near Clovis, N. M. to the Gulf of Mexico, interrupted by only four dams along the way.

One of the Brazos’ four dams created Lake Granbury, which supplies water to about 250,000 people in Granbury and about 15 other towns and cities in North Texas. But Lake Granbury is also connected by two pipelines to the Squaw Creek reservoir, because the body of water that keeps Comanche Peak’s reactors from melting down can’t be subject to the vagaries of Texas rainfall patterns. By federal law, the Squaw Creek lake must be maintained at a consistent level.

One pipeline brings water from Granbury to the plant’s reservoir when the levels there drop below a certain limit; the other is used to pump excess water from the Squaw Creek reservoir back to Lake Granbury, 15 miles to the north. Even when drought lowers the water levels in the Brazos and Lake Granbury, the Brazos River Authority must meet its federally mandated charge to keep the Squaw Creek reservoir full.

Luminant’s environmental impact documents show that each of the two existing reactors uses a million gallons of water every minute for the circulating water system that provides cooling. The new, higher- capacity ones will need 1.2 million gallons of coolant water per minute. In order to meet such a huge demand, Luminant will draw 103,717 acre feet per year from Lake Granbury. (An acre foot is the volume of water that would cover one acre to a depth of one foot.) That would be about three-fourths of Lake Granbury’s total storage capacity of 136,823 acre feet, according to the Brazos River Authority.

The water needs of Lake Granbury’s other customers pale beside that of the plant – 2 billion gallons per year in 2006, according to the river authority, versus 33 billion to be used by the expanded plant, drawn from both Squaw Creek and Granbury. And in 2006, a particularly dry year, Lake Granbury couldn’t meet the existing demand. “Many customers had to rely on their wells” that year, according to the river authority’s 2008 planning report.

A river authority spokeswoman said in an e-mail that the agency expects to be able to meet the water needs of the expanded plant and other customers. In July, the agency stated that it would meet increased demand by diverting water from Possum Kingdom Lake to Granbury.

Nor does the plant simply circulate the water through its reservoir and then send it back to Lake Granbury. Luminant’s Lucas estimated that 60 percent of the water from the expanded plant will evaporate into the atmosphere rather than going back to the river.

“That’s an incredible admission,” Harper said. “The next logical question … is, if it evaporates into the sky, will it hover over this area and rain back on Somervell County? No. It is going elsewhere, and it will be lost to the area’s dwindling water sources.”

There are other problems with the plant’s water source and the wildlife it supports. Glen Rose resident Jack Cathey, a conservationist who monitors the wildlife around the plant, told the January gathering that the frogs, fish, and soft-shell turtles of Squaw Creek are disappearing. He said he had measured the temperature of the discharge water, and “it is 104 degrees Fahrenheit as it flows down Squaw Creek on its way to the Brazos.” (Besides being pumped back to Granbury, some of the reservoir’s overflow water is also released to the creek below it, which flows into the Brazos.) His findings should be viewed as an “early warning sign that something is wrong,” he said.

Lucas responded that the two new reactors, which will use a different type of cooling system, will reduce the temperature of the water discharged into the Squaw Creek reservoir to 93 degrees. But the problem may not be the temperatures alone. One of the radioactive byproducts of nuclear fission is tritium, which is being found in increasing amounts in the soils and waters surrounding the plant, according to NRC documents. Tritium is a known carcinogen and is often found in water, from which it goes directly into the soft tissues and organs of living beings exposed to it.

Karen Hadden of Austin, executive director of SEED Coalition (Sustainable Energy and Economic Development) who spoke at the January meeting, said the plant’s need for so much water is unacceptable in an area short on the wet stuff. “Water is going to be a key in this battle,” said the former science teacher. “With water being drawn down from gas drilling and the years of usage for the two reactors here now, this is going to be one of the major issues.”

For artist Suzanne Gentling, who lives five miles south of Glen Rose, water is already the issue. Like most county residents, she depends on a well for water, she said, drawing from the Trinity aquifer, which “is almost gone.”

Gentling said she bought her place in 1990, and the deep well worked fine until 2003, when she had to go deeper. The water table in the area has “dropped 110 feet in 10 years,” she said. “We are already in a water crisis.”

Gentling, who grew up in Fort Worth with her artist brothers, Scott and the late Stuart Gentling, marched to protest construction of a nuclear power plant in Mississippi in the 1970s. She is against the Comanche Peak expansion for other reasons as well – the radioactive waste disposal problem, the exorbitant costs, the failure to consider alternatives. But the possibility of the aquifers drying up or being polluted by radiation is enough to have her marching again, she said.

There will be plenty of places for activists to march in the coming years, if the NRC’s current crop of proposed nuke plants is an indication of things to come. With global warming now accepted as a threat to the planet by many of even the most die-hard naysayers, nuclear power, touted as “clean” by its proponents because it produces no greenhouse gases to speak of, is enjoying something of a renaissance.

As of the first week in January, there were 17 license applications for new or expanded plants pending before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which has created an Office of New Reactors to handle the workload. Two applications besides Luminant’s are in Texas: The South Texas nuke plant in Matagorda County, a few years older than Comanche Peak, wants to add two new reactors, and Exelon, one of the largest utilities in the country, wants to build a new twin-reactor plant in Victoria.

Luminant’s license application calls for two 1,700-megawatt reactors designed by Japan’s Mitsubishi Corp. The utility has already increased the generating capacity of the original 1,150 megawatt reactors by 4.5 percent. If the new reactors are built, the combined capacity of the four units would be 5,900 megawatts, enough electricity to run approximately 3.5 million homes, according to the Edison Electric Institute.

Stephen Monarque, project manager for the Office of New Reactors, said Luminant is the only utility asking for permission to use an unapproved reactor design. Monarque told Fort Worth Weekly that NRC rules don’t prevent the company from proposing new reactor designs, “but they do so at their own risk. … They cannot build anything there until this design is approved,” which will take at least three years, he said, “with no guaranteed outcome.”

That uncertainty doesn’t seem to worry Lucas. In spite of Monarque’s caution, the Luminant VP told the Weekly at the meeting in Glen Rose, “We are confident that [the Mitsubishi design] will be approved by the NRC. … It is a pressurized water reactor, like the Westinghouse ones there now, but it has features to make it more reliable and more efficient. I am very sure it will pass the NRC test – otherwise we wouldn’t be doing this.”

Applying for a plant license three years before the reactor design is likely to be approved is a “more efficient way to go,” he said. Is there a plan B, if the NRC gives Mitsubishi a thumbs-down? Lucas didn’t respond.

Even if Luminant gains NRC approval for the design, the new reactors won’t be generating electricity anytime soon. Beyond the three-year reactor vetting period, construction could take 10 years or more, meaning the new units would likely be coming on line about a decade before the current reactors’ 40-year licensing periods end. The new reactors would be licensed for another 40 years.

That scenario of nuclear ad infinitum in Somervell County is one that Burnamsuspected years ago. .

“We always feared that when Comanche Peak got about halfway through its licensing stage, the utility would try to get the license extended one way or another for another 40 years,” he said. And that very likely means another 40 years of radioactive waste stored there. “Comanche Peak will be a permanent nuke waste dump, just as we [the anti-nuke groups] predicted back in the ’70s,” he said.

Burnam expects to be the lead plaintiff in the planned lawsuit because he lives on Fort Worth’s Near South Side and is within the 50-mile radius zone that the NRC deems vulnerable in case of a nuclear accident. “I didn’t want to start this battle all over again, but it looks like that’s what we are going to have to do,” he said.

At the January meeting, Burnam told the agency that as a legislator he represents more than 150,000 people who are also within the vulnerable zone: his constituents in Fort Worth House District 90.

“This is not just about the residents of Glen Rose,” he said.

Older, grayer, and maybe wiser, but with no lessening of their youthful anti-nuclear sentiments, Burnam and Hadden held an impromptu reunion with other anti-nuke activists from around the state at the Glen Rose meeting. Among them was Mavis Belisle of Dallas and Amarillo, who has monitored the operation of the Pantex nuclear weapons arsenal in the Panhandle for the past 15 years.

While most of the environmental issues discussed that day centered on the waste and water, Burnam raised the issue of cancer. He said that research over the years since the plant opened shows a “vast increase in cancer deaths in the area.”

From 1990 through 2004, the most recent year for which mortality data is available, the Texas Cancer Registry shows that Hood County, which is north of and generally downwind of the plant, has recorded an average cancer mortality rate (deaths per each 100,000 residents) of 219.8 during that period compared to the state rate of 192.7. Rates of both fatal and nonfatal cancers also showed divergence between Hood and the state in general. The rate for Hood, where Granbury is located, was 509.7 per 100,000 residents, compared to 449.2 for the state.

Somervell mortality and incidence rates, on the other hand, were lower than the state’s, coming in at 187.8 and 423 to the state’s 192.7 and 449.2 respectively.

Hood, made up mostly of rural retirement communities and whose major income source is tourism, posted cancer rates even higher than the heavily industrialized and polluted Tarrant County, which had a mortality rate of 215 during those years.

“There was only one major industry introduced into these two counties during this period, and it was Comanche Peak,” Burnam said. He called on the NRC and Luminant to provide a “rational, intelligent environmental impact statement” that will show clearly how many deaths can be expected from the increases in background radiation from an expanded plant, as well as what can be expected in case of a radioactivity accident.

Other speakers asked Glen Rose residents to consider the cost to people in surrounding counties and to the environment during the entire nuclear fuel cycle, from uranium miners in New Mexico (who have some of the highest cancer rates in the nation) to the workers in the fuel processing and assembly plants, to the dangers of transportation and disposal of the waste.

“We who benefit from the electricity are responsible for the full chain of events in this cycle, from the beginning to the end,” Jan Sanders of Dallas said.

Ironically, Harper pointed out, the residents of Somervell and Glen Rose do not get their electricity from the plant. The area is served by co-ops that buy from Texas-New Mexico Power.

Paul Harper, Debbie’s husband and one of the few local dissenters who spoke, talked about nuclear waste. “We take our garbage to the local dump or have it picked up and hauled off somewhere else, yet we keep this radioactive waste here. … And now we want to increase the storage of [this] waste in our county. I don’t think it’s wise to keep increasing this waste without figuring out what to do with it,” he said. “This company needs to figure out a solution to this before our next meeting.”

Voices like his were outnumbered by a “bring ’em on” chorus from most of the folks who were there who live in the county and have seen Somervell go from one of the poorest counties in the state to one of the richest since becoming host to Comanche Peak.

When construction of the nuke plant began in 1976 along the small, meandering Squaw Creek, the county’s economy was based solely on a dwindling agricultural base. But all that changed dramatically that year, when Glen Rose suddenly became a boomtown of well-paid construction workers and nuclear engineers. By the mid-1980s, according to the Texas Handbook Online, the county had nearly $2 billion worth of taxable property and $141 million in annual wages, a whopping 11,000 percent increase since 1975. Annual wages have dropped, as the plant employs only about 100 workers, but the property tax largess is still significant.

“We want this expansion,” Somervell County Judge Walter Maynard said, noting that most of the dissenters were from out of the county. The plant has been a “good neighbor,” he said. Somervell and Hood County commissioners even passed resolutions supporting the expansion – with the help of Jan Caldwell, community relations manager for the nuclear plant, who acknowledged to a Dallas Morning News reporter that she had “helped write some of the resolutions.”

Expanding Comanche Peak is part of Luminant’s push for more “green technology” according to Lucas, who proudly pointed out that Luminant is the largest purchaser of wind power in the state. He touts nuclear as another answer to global warming because it produces minimal amounts of greenhouse gases and reduces the company’s reliance on coal.

Lucas dismisses the waste issue as one that will be “solved by the government,” in spite of the fact that the government has not solved it in 50 years. The utility VP believes the answer lies in reprocessing the waste, creating an endless supply of fuel for more and more nuke plants. It’s an idea that drives anti-nuke activists nuts and one that was rejected by the federal government years ago as too costly and dangerous, because the reprocessed fuel, rich in plutonium, could be used to make nuclear bombs.

Even the area’s congressman, Democrat Chet Edwards, a strong proponent of nuclear energy, is troubled by the waste problem. Harper reported on her blog that Edwards told a public gathering of Glen Rose residents at a local café in 2007 that he believes there should be “a small number of nuclear waste repositories rather than each nuclear site storing its own waste” because of the danger of a terrorist attack.

With no place to go, the high-level waste has been stored at Comanche Peak for 19 years in fuel pools that were designed to hold the stuff in seven-year cycles. At the end of each cycle, according to the plant’s original plans, the fuel would be removed and trucked to a high-level repository for permanent storage, and a new cycle would begin.

But there is still no such place. Yucca Mountain in Nevada is the federal government’s choice for a permanent repository for its millions of tons of highly radioactive wastes now stored at nuke plants and other nuclear facilities around the country. But the site has come under fire from Nevadans who don’t want the nation’s most dangerous waste in their backyard and from Native American tribes in the area who view the mountain as sacred. Geologists have raised serious questions about the area’s seismic stability over the millions of years it will take for the waste to decay. The Department of Energy, which will run the facility if it ever opens, has applied for an operating license from the NRC, but as yet one has not been issued. Last year the U.S. Senate, led by Democratic majority leader Harry Reid of Nevada, an outspoken opponent of the project, cut the energy department’s budget for site evaluations and exploration at Yucca Mountain by $495 million, forcing the contractor, Bechtel, to lay off workers and put the project on standby. At the time Reid told the Associated Press he wouldn’t be happy “until the Yucca Mountain budget is cut to zero.” In August, the DOE announced its “latest revised estimate” is that it will cost $96.2 billion to build the repository, transfer the waste to it, and monitor the site just for the next 150 years.

For those new to this nuclear drama, there is a cautionary tale.

It was 1973, and Texas Utilities announced with great fanfare – and confidence – that their first nuke plant, with its twin reactors, would be open by 1980 at a cost of $779 million.

They couldn’t have been more wrong. The utility and its contractor, Brown & Root of Houston, had no clue just how much damage a then-unknown bookkeeper from one of Dallas’ oldest blue-collar neighborhoods would be able to do to their plans.

By the time the plant’s second reactor finally came on line, it was 1993. The total construction had taken 19 years, and the cost had ballooned to $11 billion. By then, the plant had been completely redesigned, large segments of the containment buildings had been torn out and rebuilt, Brown & Root had been replaced by Bechtel Corporation as construction manager, and a citizen watchdog group had won an unprecedented contract to put its own safety inspectors inside to oversee the plant’s first five years of operation.

And Dallas housewife and part-time bookkeeper Juanita Ellis had become a household name for forcing one of the most powerful utilities in the nation to almost totally rebuild a nearly finished nuclear power plant because of a litany of safety violations and shoddy workmanship that she – and the whistleblowers who flocked to her side – uncovered. A later internal NRC investigation found that its local inspectors had either missed the glaring deficiencies or looked the other way.

Ellis was an unlikely tilter at nukes. When Texas Utilities first announced its intent to go nuclear, she was 38, worked part-time at her husband Jerry’s nursery in Dallas’ Oak Cliff neighborhood, and kept books for her church. The couple had no children.

She had never been involved with the Dallas-Fort Worth area’s small but vocal group of anti-nuclear activists, whose focus before Comanche Peak had been the nation’s nuclear weapons arsenal. But Ellis had read about the dangers of a nuclear power plant accident in one of her husband’s gardening magazines, published locally. The author was a Continental Airlines pilot named Bob Pomeroy. Shortly after, she read that her utility company, Dallas Power & Light, would be a partner in the construction of a nuclear power plant. She contacted Pomeroy and, along with four other Dallasites, one of whom was well-known in local government circles as an outspoken socialist, they formed Citizens Associated for Sound Energy, as a vehicle to oppose the plant.

When the six went before the Dallas City Council (which at that time had jurisdiction over Dallas Power & Light) to voice their objections, all hell broke loose. Unknown to the small band of dissidents, the meeting was monitored by the Texas Department of Public Safety. (It was the 1970s, the Cold War was still hot, and those who opposed nuclear power generation in any form were suspect.)

Pomeroy, who spoke for the group, was labeled a “subversive” by the DPS, put under surveillance, and a file kept on his activities. An anonymous letter was sent to the pilot’s company outlining his “anti-nuclear” activities and suggesting that he might fly a plane into the reactors once they were built. Pomeroy was so unnerved by the slimy tactics that he dropped out and moved to Arkansas. (Years later Pomeroy won a lawsuit against the DPS, forcing the agency to apologize and purge his file, which said among other laughable things that he had been seen “with a known Socialist.”)

Ellis wasn’t scared off. She just got mad. She took on the leadership of the group, and by 1979 CASE was a full intervenor in the NRC licensing proceedings. Two public interest groups in Fort Worth, Citizens for Fair Utility Regulation (CFUR) and ACORN, joined the fight.

Legal proceedings were one route taken by opponents. The other was civil disobedience. In 1979 and 1980, a group called the Comanche Peak Life Force, made up of activists from Fort Worth, Dallas, Denton, and Austin, including Belisle, scaled the fence at the construction site in nonviolent protests. Trials were held at the old limestone courthouse in Glen Rose, with the first ending in a hung jury and the second in convictions for more than 50 protesters. Some were put on probation; most were simply fined.

Hearings on the plant’s license were held before the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board, whose judges traveled to Fort Worth and Glen Rose to hear testimony. They turned into the longest and at times the nastiest proceedings in the agency’s history. They were also costly to the interveners, who relied on donations to stay in the game. By 1982, CASE was the only one left standing.

Ellis persevered through numerous hearings, along with a number of whistleblowers, most of whom had been fired by Brown & Root or one of its subcontractors after they persisted in reporting construction problems that could endanger the safe operation of the plant. They produced so much damning evidence of safety violations, cover-ups, and illegal firings that by 1986, when the construction was almost done, an ASLB judge ordered the utility back to the drawing board for what would be an almost complete redesign and rebuilding of key structures. Those deficiencies started on day one, according to testimony from workers and engineers and NRC documents, with Brown & Root’s overexcavation of the foundation for the reactor buildings and the company’s subsequent quick fix, which was to throw rock and rubble back into the hole and pour grout around them.

Other irregularities quickly followed: Whole sections of reinforcing steel were left out of the first containment building; the concrete dome of the same building fell off in large chunks because the concrete had been poured in the rain; concrete foundations under the containment buildings and the fuel pool building were poured and left to cure in freezing temperatures, which made the concrete brittle and prone to cracks. Welders testified that the welds on the liners in the fuel pool itself, designed to hold the circulating cooling water that surrounds the highly radioactive spent fuel rods, were defective because they were made under unclean conditions on a surface that was supposed to be “mirror-clean.” And insulation material, used on wiring and as barriers inside the containment and fuel pool buildings to mitigate the spread of a fire, were found to either melt or catch fire under extreme temperatures.

Excessive numbers of vendor welds were found to be defective in prefabricated materials used in other critical safety areas. Pipe-hanger supports, which ensure the stability of hundreds of miles of piping carrying radioactive water under extremely high temperatures as well as coolant water needed in case of an accident, were found to be defective and prone to failure. All had to be replaced. Widespread use of “unqualified mechanical and welding inspectors” was documented. One whistleblower testified that he had been “ordered by every foreman I worked for to make illegal welds when necessary” to get the job done on time. One female welding inspector who worked for Brown & Root said she rejected almost all the welds she inspected, and for that she was soon shuffled off to a small building on site “to sit alone and do nothing but useless paperwork.”

Following her testimony (she was 28 and pregnant at the time), the inspector was badly beaten in the backyard of her mobile home late one summer evening by two unknown men; she suffered multiple bruises, cuts, and broken ribs. She told a reporter later, “I never had any enemies before I agreed to testify” for CASE.

But by 1988, Ellis was exhausted. She had fought the good fight, and while she had not stopped the plant, she believed she had made it safer. TU Electric was by then more than desperate to get its license. In an unprecedented agreement that shocked her longtime supporters and colleagues around the state, Ellis agreed to drop her fight in return for a $10 million settlement from TU and a contract that gave CASE inspectors access to the plant for five years and Ellis a seat on its oversight board. The company’s CEO was forced to publicly admit that the utility had made major and dangerous construction errors that would not have been found had it not been for Ellis and her crews.

Half the $10 million went to CASE and its attorneys and the other $5 million to about a dozen whistleblowers, many of whom had lost their jobs and had been blacklisted in the industry. Ellis said following the settlement that she did it for the whistleblowers, to honor their courage and sacrifice. Those who knew her at the time never doubted her word. Throughout the long hearing process, Ellis continually worried about the workers and their families.

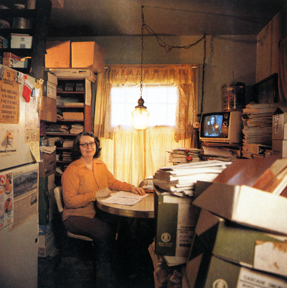

Burnam said that the new fight could use another Juanita Ellis. But it is unlikely it will be the original. Today she still lives with her husband Jerry in the small, 1950s-era frame house in Oak Cliff that once was filled with so many boxes of documents that one reporter dubbed it a “filing cabinet with a bathroom.” Numerous calls left on her answering machine with requests for comment on Luminant’s proposal to add more reactors at Comanche Peak were not returned.

Given the magnitude of the construction deficiencies eventually uncovered, who knows what tragedy might have occurred if Juanita Ellis hadn’t picked up that gardening book back in 1973.