Four white lines beckoned from a tabletop in an Austin hotel room, and Roy Stamps bent over with a rolled-up dollar bill and snorted two. The rest he offered to a buddy, who declined. “I don’t need any help staying up late,” the friend said, chuckling.

“I do,” Stamps said, finishing off the methamphetamine. “It’s going to be a long weekend. I got to be up.”

In the previous few years he’d undergone open-heart surgery, a couple of other surgeries, and six months of chemotherapy for colon cancer. Forty pounds had vanished from an already lanky physique. Yet here he was at 68, hosting a four-day music gathering, running sound for the artists, hanging out at after-hours guitar pulls, and generally being the affable and enthusiastic ringleader everyone expected – even if he needed a little unnatural boost to keep going.

In 17 months he’d be dead. But, on this June night in 2007, like so many other nights through the years, Stamps was right where he wanted to be – roaring, happy, high, surrounded by friends, and playing a pivotal role in bringing music to the people. As a Fort Worth-Dallas concert promoter, he’d organized shows featuring Johnny Cash, Chuck Berry, Waylon Jennings, George Jones, Rick Nelson, Jefferson Airplane, and many others. But the former PR man took the greatest pride in his longtime friendship with Willie Nelson and in his role in promoting the singer’s inaugural July 4 picnic at Dripping Springs in 1973, which history dubs the “Country Woodstock.”

Concert planning, like so much of the music biz, is riddled with potential land mines, and Stamps stumbled over more than a few. Mistakes, bad luck, and being a soft touch meant he rarely made much money. “There were never any big home runs hit,” his son Trey said. “I called Dad a chump one time, and he got pissed off – I nearly got my ass kicked. He was wealthy with friends, though; there was never any doubt about that.”

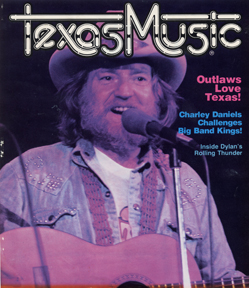

He’d been in the thick of the biggest music phenomenon Texas has ever seen – the 1970s Outlaw explosion with Willie, Waylon, and the boys – but had little to show for it beyond memories and faded mementos. Back then, musicians regularly flopped on his couch when he and his wife Sylvia and their children lived in Dallas. The wandering minstrels hit him up for advice, shelter, pills, and the occasional loan. And they counted on him to boost ticket sales with advertising wizardry and to promote them in the original Texas Music magazine he published.

You’ll find little by Googling “Roy Stamps” and “Texas Music,” however, and that’s a shame because he had a knack for hopping on runaway trains and providing needed guidance, even as the crazies around him continued pouring on the coal.

Stamps wouldn’t say it, but being overlooked in Texas Music history was more painful than any missed paydays. He wanted to be the guy who made things happen; he just lacked the golden touch. Disappointments, financial problems, a prison stint, and health issues finally waylaid him, but he was smiling to the end. Cancer killed him on Nov. 20.

“Nobody knows better than I do that Roy had warts, but he was a remarkable human being, and I was blessed to have been his wife,” Sylvia Stamps said.

Tense best describes my introduction to Roy Stamps six years ago – unusual since happy-go-lucky was more his style. But he was upset about being called a thief in a Fort Worth Weekly story on author Jay Milner (“Maddog in Winter,” Aug. 8, 2002). Milner had described how Nelson and other musicians held a benefit concert in Dallas and raised $60,000 to help establish the original Texas Music magazine in 1976. Milner was editor, and Dallas-based PR man Stamps was publisher. The glossy mag was well written but folded in the first year.

Milner accused Stamps of siphoning off money to buy nose candy. I printed his claim but withheld Stamps’ name since I wasn’t able to track him down for comment. Once the paper hit the streets, my phone rang. “This is Roy Stamps, and I’m the guy Milner was talking about, but I didn’t steal any money from the magazine – I lost my ass on that deal,” he said. “It nearly bankrupted me. I’m sure as hell glad you didn’t print my name.”

There was no denying the drug accusation. Stamps and Milner agreed that almost everybody associated with the magazine was high as a kite. Hell, they were hobnobbing with rapscallions like Nelson, Jennings, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Steven Fromholz. But Stamps insisted no thievery occurred. The magazine was short on cash from the get-go, a business plan had never been written, and Milner hadn’t invested a dime, while Stamps had sunk about $18,000 into the project and lost it all, he said.

An article in the Feb. 1, 1977 issue of D Magazine, under the headline “Discord at Texas Music,” described the magazine as showing “great promise” but blamed its downfall on distribution problems.

Years later, Stamps agreed that poor distribution killed the rag. He blamed the newsstands. “They don’t pay you until about the fourth or fifth issue comes out,” he said, “because they’re betting that you are going to fail.”

The 1977 article described how “cash got tight, and slowly payments – to writers, artists, and then to members of the staff – stopped.” There was “no love lost” between Milner and Stamps, the story said.

A quarter-century later, Stamps wanted Milner’s phone number – he wanted to call his old acquaintance and set the record straight. I talked to both men afterward. They had remained civil during their conversation, but neither would budge from their views of the magazine fiasco. They never spoke again.

The following year, I wrote about Willie Nelson’s 70th birthday (“Poet, Picker, Prophet,” May 1, 2003). Again the phone rang.

“I’ve read a lot of stories about Will over the years, but that was one of the best ever.” It was Stamps, and this time there was no tension. Sincerity, charm, and enthusiasm were his calling cards, but above all he was a storyteller. During a long conversation, he described a damn-near unbelievable life: As a teenager in Gainesville, he’d promoted an Elvis Presley concert – and lost money. In Fort Worth he’d worked alongside comedian George Carlin and newsman Bob Schieffer as a radio disk jockey in the 1950s.

While attending Texas Christian University, he’d chauffeured black soul singers Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson during a tour through the segregated South. In 1960 he helped Texas millionaire Lamar Hunt promote the American Football League’s inaugural season. He was one of the first newsmen on the scene at Parkland Hospital after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, he co-promoted Nelson’s first July 4 picnic, and so on.

Right, I thought, and he was an astronaut and he owns the bar. But then he said something that pricked up my ears.

During an interview for the “Maddog” article, Milner had described the first time he saw Nelson perform. During a set at The Western Place in Dallas in 1973, the still largely unknown singer asked the crowd if he could play some freshly written material, then performed all the songs that would be released the following year as Phases and Stages – one of Nelson’s early masterpieces and my favorite album. I mentioned this to Stamps, who said matter-of-factly, “I was the sound man at The Western Place and recorded Willie’s set that night on a reel-to-reel. It was a great night. Willie wanted to send Atlantic Records a demo of his new songs and asked me to record his set. Waylon showed up and played a few songs, but he was pretty wasted.”

It all sounded hard to believe. “I can burn you a CD if you like,” he said.

I was thunderstruck. And intrigued. Maybe this guy was legit. To my surprise, the CD arrived days later and was as fascinating and exciting as I’d imagined. Stamps sent other recordings, including one of a live Ray Charles performance at the same bar. Later, he mailed me the entire discography of reclusive songwriter Mickey Newbury, whom he greatly admired. Stamps said he was organizing an annual concert in Austin to honor the man and his music.

Our phone conversations grew more frequent, and he eventually invited me to his house in the little burg of Venus, a half-hour drive southeast of Fort Worth. Stamps was in his mid-60s then, tall, thin, and a real character – slightly warped and completely thrilled to spend an evening smoking grass, sitting on his couch, spinning obscure albums on an old turntable, and sharing memories of musicians and their shows.

Drugs, particularly crank, can spur illusions of grandeur and intertwine fantasy and reality. But Stamps’ tales rang true most of the time. Sometimes I would run one of his stories past third parties for confirmation, and they’d back his claims. Other times, Stamps might dig up a rare recording, photo, concert flier, or something else to show he wasn’t full of shit.

Before long, we were involved in a business deal that, like much of Stamps’ concert promotion efforts, bore no financial reward but spurred some great times and lasting friendships. “I want you to help me write a book about Willie,” he said one day. That was music to my Willie-loving ears.

The plan was for Stamps to record his memories of the early Outlaw years, roughly 1970 to ’75, on cassette tapes, and ask others, including longtime friend Connie Nelson (Willie’s wife in those years), to do the same. I would transcribe the recordings, fact-check, and string chapters together. Included with each book would be a copy of the rare Phases and Stages demo. When Willie and Connie’s daughter Paula got married a few years ago, Stamps attended the wedding and asked his old buddy’s permission to release the recording.

“It’s yours – do whatever you want with it,” Nelson had replied.

Meanwhile, a literary agent had given us an enthusiastic thumbs-up.

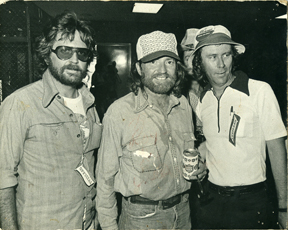

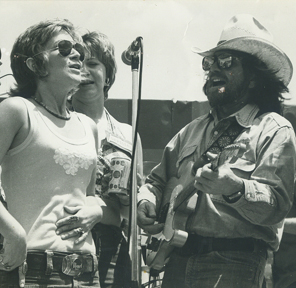

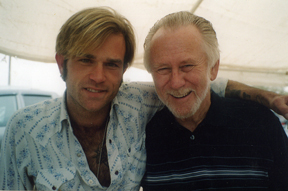

So Stamps began dictating into a recorder and quickly filled three hours’ worth of cassettes. The stories were wild and fun; many quotes used here came from those tapes, as well as from his journals and from our conversations over the last few years. (The old, previously unpublished photos accompanying this story came from Roy’s collection. For instance, the Phases and Stages demo was recorded on the night of Nelson’s 40th birthday – April 30, 1973. The bar locked its doors at 1 a.m., but the party continued inside. “Quite a roar going on, a good guitar pull, lots of weed being smoked,” Stamps said.

“About 3 in the morning somebody started beating on the back door. Willie answered it, and it was a police officer. He walked in, and the smoke was so thick you could cut it with a knife. [Pedal steel guitarist] Jimmy Day was sitting there at a table rolling joints as fast as he could. Willie looked at Jimmy and said, ‘You want to hold up on that a minute?’ Jimmy looked around and saw the officer in blue, and he turned a little blue himself.

“Willie put his arm around the officer, and they went outside. The next thing you knew, Willie came back in and said, ‘We’ve got 15 minutes to get out of here.’ So we loaded everybody up … and headed over to my house in Richardson, and the roar continued all that night and up to about noon the next day when people just started falling down on the floor. That was when we had legalized [preDELETEion] speed – black mollies, greenies, the great speckled bird, LA turnarounds. We had them in candy dishes sitting around. We stayed up a lot back then.”

Stamps always said a good PR man excels at wining and dining, and he was particularly adept at the former – although “wining” is misleading since Stamps preferred tasty weed and potent speed over alcohol.

When Nelson went to record his breakthrough album Red Headed Stranger in 1975 at a Garland studio on short notice and with little studio time, he phoned Stamps.

“Bring anything you got that will keep us awake for awhile,” Stamps recalled Nelson saying. “I grabbed a half-bottle of black mollies and headed on out there. I think they recorded for three or four straight days around the clock. Willie sent me to the airport to pick up a friend of his, who I better not mention here. I picked him up at Love Field, and the guitar case he was carrying was filled with marijuana, and that’s what helped them finish the album.”

During this time, the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra called Stamps and asked if he could convince Nelson to sit in with them for a half-dozen songs at a concert. Stamps relayed the message, and Nelson agreed. After the show, somebody handed Nelson a check for $8,000 – big money back then.

“Willie looked at me and said, ‘I didn’t know I was getting paid. I thought this was a freebie,’ ” Stamps recalled. “I said, ‘I didn’t know you were getting paid either or I would have asked for a commission.’ Willie just laughed. I didn’t get my commission either.”

Local music history may have forgotten Stamps, but his erstwhile partner in promotions back then is still remembered. Gene “Gino” McCoslin gets mentioned in articles, books, and conversations about the Outlaw era, such as author Joe Nick Patoski’s recent release, Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. Veteran actor Rip Torn (as Dino McLeish) parodied McCoslin in the 1984 movie Songwriter. History glorifies larger-than-life characters such as the notoriously wired, eccentric, and sticky-fingered McCoslin, while overlooking sincere guys like Stamps.

“Roy was a good promoter, but he had a lot to overcome,” Connie Nelson said with a laugh. “Roy had to finagle his way past Gino to get things back on track. I remember Roy always being the levelheaded and fun one. He always put a smile on his face and went on through.” Sylvia Stamps liked McCoslin but wanted to strangle him half the time.

“Gino was the flamboyant P.T. Barnum hey-look-at-me guy, and Roy was the one sitting in the office until 2 in the morning writing copy for the programs and doing layouts and paying the bills,” she said of her husband. “Roy took care of business.”

Roy Stamps described McCoslin as a troubled genius – creative, funny, handsome, and charismatic, but also conniving, paranoid, criminally minded, seldom without a pistol, and cranked to the nth degree.

Musicians accused McCoslin of dipping into gate receipts, boosting ticket sales by advertising gigs with artists who hadn’t been booked, selling more tickets than there were seats, and various other scams.

Friends say snippets of dialogue in Songwriter are vintage McCoslin, such as a scene where “Dino” is bitching about promoters not being appreciated, or when an artist asks after a show how they fared, and a promoter says something to the effect of, “I did OK, but you were robbed.” McCoslin would later crack up, spend time at the Rusk state mental hospital, and then commit suicide in 1994. “Today we would know Gino as bipolar,” Stamps said. “Back then we just thought he was crazy.”

The craziness was alluring.

“Those boys were a hoot,” said Sue Ann Zerre, who worked as a receptionist for Stamps and McCoslin at their ad agency, appropriately named Joint Ventures. “Roy started out as a very straight guy with a tremendous amount of potential, but when he and Gino got together, Roy wanted to be a gangster. … Roy was the straight guy on every level, and Gino was the wild man.”

At the ad agency, McCoslin hid pills in ceilings and under desks. Zerre even remembers a guy arriving one day with a bag of stolen bank money covered in red dye – a dye-pack had exploded. An unsuccessful attempt to bleach out the dye resulted in the money being thrown away.

“Everybody loved Roy and everybody put up with Gino,” Zerre said. “Roy was a kind person, and he let a lot of things slide because Gino was funny and kept everybody laughing. Gino would beat his chest and take credit for the great shows they did, but he was the one who was always chasing everybody around with guns.”

Stamps lived vicariously through McCoslin but didn’t have the mental makeup to become a gangster himself. He cared too much about making others happy, particularly Nelson, whom he viewed as a brother. “I remember when Roy gave Willie money to pay his electric bill,” Zerre said. “I remember when Willie would crash at Roy and Sylvia’s house and sleep on the couch. I covered him up more than once. Nobody was famous back then. Roy helped a lot of people out.”

Bunking at the Stamps home usually involved late nights spent listening to music, discussing gigs, and plotting schemes to make everybody rich and famous. One idea they came up with but later abandoned was to print “Willie Nelson” on hundreds of ping-pong balls and scatter them on a Nashville golf course. Another idea, which they pulled off, was to have a party on July 4 and bring together rednecks and hippies for a beer- and marijuana-soaked, chicken-fried love-in.

Nelson envisioned a medium-sized party in a rock quarry outside Austin. The enthusiastic promoters thought big and printed up 5,000 tickets. Nobody expected 50,000 fans to overrun the place. Stamps’ teenage son Trey accompanied his father to the event and recalled stopping for breakfast at a small restaurant in Dripping Springs. Early concert arrivals were swarming, and the lone cook was snowed under. True to his nature, Stamps offered assistance without being asked – or paid.

“Dad helped him cook pancakes,” Trey Stamps said.

The concert was equal parts fun and disaster. The hippies and rednecks got along, but food and restroom facilities were a joke, and the small roads leading in and out were congested for miles. Hiring the Bandidos biker group to run security – and paying them in beer – was a mistake. At midnight the power was out, the drunken crowd restless, the bikers aggressive.

Promoters envisioned a debacle reminiscent of Altamont Speedway a few years earlier. But the stage crew rigged up a small sound system using backstage buses for power, and Tom T. Hall walked on stage with his guitar and sang “Me and Jesus,” and everyone mellowed.

In the end, as usual, McCoslin pocketed money and scrammed, leaving his partner to sort out the mess. “The artists loved Roy,” Zerre said. “If a show bellied up, the artists always got paid.” Roy always took up for the artist.”

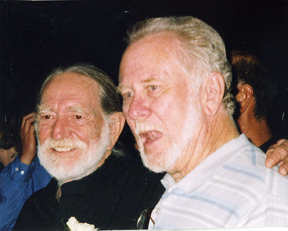

That devotion wouldn’t be forgotten. Once Nelson hit the big time, he hired tough managers to handle business. Small-time promoters and flim-flam men like McCoslin were mostly shoved aside. But Nelson never forgot Stamps. Even when he was getting $25,000 per concert, Nelson would come back to North Texas and cut his price to $5,000 for a Stamps-promoted show.

“Willie would give Roy a couple of concerts a year to help him out financially,” Zerre said.

The Weekly called Nelson’s publicist to request an interview, but she said he doesn’t discuss for public record his friends who have died. There have been too many, she said, and “it hurts him too much.”

Connie Nelson described Stamps’ relationship with the singer this way: “He was one of Willie’s closest friends back in the Fort Worth-Dallas days,” she said. “Roy probably thought of himself more as a promoter, but Willie always looked at him more as a friend, and that’s why he let him promote a lot of the shows.”

After Hollywood and international fame beckoned, Nelson spent less time with old Texas cohorts. The diminished communication hurt Stamps, but his loyalty never wavered. “As Willie got bigger and bigger, it wasn’t that he drifted away from Roy, but to get any piece of Willie’s time, even for his kids, was tough,” Connie said. “But he always considered Roy one of his closest friends.”

Trey Stamps ran into Nelson in the late 1970s and asked why his dad hadn’t been added to the crew. “He said Dad wasn’t tough enough, he was too nice to be a part of Willie’s management team,” Trey said. “He wasn’t an enforcer. You’ve got to be a real prick to do that. Dad was loyal and nice to a fault, and that was his downfall.”

Stamps’ love affair with music began as a teenager growing up in Gainesville. Enamored of “race music” – the term rock-and-roll had yet to be coined – Stamps soaked up records by Big Joe Turner, The Midnighters, and other black artists. Local record stores didn’t stock the music, so Stamps drove to Denton to “blow my weekly allowance” on 78-rpm records.

By high school, he’d compiled an impressive collection. He bought a Silvertone hi-fi turntable and began deejaying at sock hops. His Sunday school teacher owned radio station KGAF and gave Stamps a one-hour show spinning his own records. Stamps earned no salary but kept 20 percent of any advertising he sold.

“That really started my trip into radio, music, advertising, and promotion,” he said. In 1954, Stamps was infatuated with a new artist and convinced his boss to put up $300 and let him promote a show at a Gainesville baseball field featuring this singer named Elvis Presley. But Presley wasn’t yet a star, and the concert lost $108. “Elvis said he would come back and play again for free, but that never happened,” Stamps said. After high school, Stamps enrolled at TCU, majoring in advertising with “a minor in party,” he said.

In 1956, he sent tapes of his Gainesville radio shows to Fort Worth-based KNOK and was hired sight unseen. “It was the only black station in town, only they didn’t call it ‘black’ back then,” he said. On his first day at work, the station manager met Stamps and started hedging. “I didn’t know you were white,” he stammered. “The young white kid persisted, asking why he’d been hired in the first place.

“In so many words, he said I had a great knowledge of music and ran my old program so that it flowed well,” Stamps said. “I started to laugh and he looked at me a little funny. Then this big smile came across his face.

“Hell, it’s not TV, I guess you can work here if you’re not afraid of us,” the station manager finally said.

Stamps earned $2 an hour and worked from sunup to sundown on Saturdays and Sundays. One afternoon, a little-known soul singer stopped by to pitch a new record. He introduced himself as Sam Cooke. “He was a little taken aback that I was white, but we got past that,” Stamps said. Cooke was also carrying a reel-to-reel tape with an unreleased song called “You Send Me” and asked Stamps if he wanted to hear it.

“After the first 10 seconds, I stopped the tape and asked if I could play it on the air,” Stamps said. “He didn’t have any objections, so I did just that. The phone lines lit up, and before the afternoon was over I must have played it four or five times while I interviewed Sam on the air. He left and took the tape with him. The next day the morning disk jockey called me and wanted to know what the hell I played on Sunday, that he was getting all sorts of requests for this record he didn’t have. Got my butt ate out pretty good for that. I learned later I was the first person ever to play ‘You Send Me’ on the air.”

Cooke and singer Jackie Wilson later hired Stamps to drive them around in a white convertible Cadillac on a two-week tour. “They thought it would be so cool to have a white guy doing that,” he said. “So off we went. I soon found out things I had really never realized – here were two men with the number-one and -three songs on the charts, and they couldn’t eat in the same café that I could. We had to eat in the black cafés, stay in rundown black motels, go to black nightclubs. They took me everywhere, and I never had a problem.”

By then, “race music” was being recorded by white artists and played on Top 40 stations such as KXOL, Fort Worth’s top station.

Stamps increased his salary by switching stations, but his new program was more news-oriented. After graduating from TCU, he married, started a family, bought some suits, and took a job at an ad agency writing copy and producing TV commercials. In 1960, Texas oil millionaire Lamar Hunt hired him to help promote the first American Football League game between the Dallas Texans and Denver Broncos at Farrington Field in Fort Worth. Afterward, he was promoted to a job in the Texans’ PR department.

Two years later the team moved to Kansas City. Stamps stayed behind and started selling ads for KXOL. Selling meant wining and dining, and The Cellar in Fort Worth was a favorite wining spot.

When President John Kennedy visited Fort Worth in 1963, KXOL enlisted staffers with on-air experience to work overtime and do mobile reports. Stamps jumped at the offer, partied until 2 a.m. at The Cellar with several Secret Service men on Nov. 21, slept a few hours at Hotel Texas, covered JFK’s Fort Worth speech the next day, then hustled over to Dallas for the parade. His news crew was among the first on the scene at Parkland after the assassination, and Stamps saw the mortally wounded president being lifted out of the car. His deDELETEion of the wound is often quoted among conspiracy theorists.

Stamps was proud of his role in reporting one of the century’s biggest news stories, but even that didn’t match the thrill he got by hanging out with musicians and helping them get a break.

Stamps first saw Nelson perform at The Cellar in the mid-1960s, and by the late 1960s they were buddies. Of course, Stamps befriended lots of itinerant pickers. He loved music, pure and simple, and was always quick to offer musicians a place to crash and party, which was a strain on his family life. He and his first wife divorced, and in 1968 he married his secretary, Sylvia, and became stepdad to her two children.

“It could get pretty chaotic,” Sylvia said. “Roy’s love of music and musicians was real evident early on, so I kind of knew what I was getting into – but not exactly. Not long after we got married, Willie came back to Texas. The frequency of musicians in the house picked up quite a bit.” After she became pregnant with their son Cayce, she stepped away from the scene. “I always loved it, but there were times when it was an interruption, and that’s putting it mildly,” she said. For Sylvia, “It didn’t hold the glamour it once did, and so Roy did a lot of hanging out with guys away from the house. But Roy just loved the industry so much, all facets of it. To take that away from him would have taken away a big part of who he was – and I’m not sure I could have even if I’d tried.”

The children were confounded by their father’s absence and antics, but they enjoyed visits by musicians and the accompanying craziness. “I grew up in a house where Willie was hanging out in the living room at a time when he was starving and nobody knew who he was,” stepdaughter Kitina Reid said. “Willie had a tendency to come in during the middle of the night, and Mom and Roy would wake me up no matter what, because they knew I adored him.”

Stamps, as usual, played deejay, sitting in his living room, digging through albums, playing a cut here, a cut there. “I remember playing ‘Whiter Shade of Pale’ for Willie one night,” Stamps said. “He was lying on the living room floor on his back, staring at the ceiling, not saying a word. After the song was finished, he said, ‘Play that again.’ So I picked up the needle, played the song again. Willie said, ‘Play it again.’ This went on and on; I must have played the song five times.” Stamps’ eyes sparkled as he reached the story’s climax: “Finally, Willie said, ‘I’ve figured out what that song is about! It’s a tarot card reading!’ I laughed my ass off about that. But, you know, he might be right.”

His ad agency focused on non-music clients such as Dairy Queen and Braniff Airlines but veered toward the uncertain world of concert promotions once McCoslin entered the picture. Musicians are professional night owls, and Stamps and McCoslin were usually game for all-nighters. “I grew up in a home where sex, drugs, and country music were everything,” Reid said. Speed was the drug of choice, and the string of late nights meant business suffered. The failure of Texas Music magazine in 1976 and the collapse of the ad agency threw Stamps into a tailspin. “Up until the point it folded, he had his own office and agency, and everything was going great,” Reid said. “I know Roy was a different human being after it crashed.

No confidence, or at the very least, damaged confidence.” Broke and scrambling, Stamps was convicted for writing hot checks but served no jail time. He eventually joined a brother-in-law in a construction business and clawed his way back toward financial security. Through it all, he never lost his yen for music. Eventually the desire returned to be in the thick of things. In 1986, he organized an old time rock-and-roll show featuring Chuck Berry, Chubby Checker, Sam the Sham, and others, backed by a 16-piece band.

But Stamps’ taste for speed hadn’t waned either; he’d begun cooking meth for personal consumption and to sell to friends. In 1989, police charged him with possessing dangerous drugs with intent to sell. He faced a long prison sentence.

The family was devastated. Trey Stamps recalled trying to raise money for a lawyer. Nelson had long since stopped using or condoning coke and speed. He told his crew, “You’re wired, you’re fired.” But when Trey cornered him after a Dallas concert, Nelson contributed generously to the defense fund. “I was scared out of my mind, thinking Dad was going to jail forever,” Trey said.

Other musicians kicked in as well. They raised enough for a lawyer, but Stamps ended up serving three years in prison.

Youngest son Cayce accompanied Sylvia on visits at the Huntsville prison unit, and he still remembers his workaholic father’s embarrassment. “He was a provider. Whether he was doing concerts or construction or through illegal means, he was always trying to provide for his family,” Cayce said. “Seeing him in that condition was tough on him. You could see it in his eyes, you could see he was ashamed.”

After his release, Stamps distanced himself from the music business, but not from music. He designed swimming pools by day, played his records at night, and went out infrequently.

Actor and musician Waylon Payne, who portrayed Jerry Lee Lewis in the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line, befriended Roy and Sylvia Stamps in the 1990s and often stayed with them when he was in the area. Payne’s mother, Grammy Award-winning singer Sammi Smith, was a close friend of the Stampses until her death in 2005.

“Roy worked real hard and sacrificed a lot and was just one step away from being able to have all the credit he always deserved,” Payne said. “It would be right there and he’d miss it, and he’d just brush himself off and keep going. And Sylvia was always right there by his side saying, ‘Yes you can.’ They loved each other a lot.”

Stamps needed a new calling and discovered it after singer-songwriter Mickey Newbury, an old friend, developed health problems. Newbury is a member of the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, celebrated for his arrangement of “An American Trilogy,” made famous by Elvis Presley.

In 1999, with Newbury battling lung disease, fans, friends, and musicians showed their love for him at a gathering in Florida. Newbury made a rare concert appearance, and another gathering was held the next year in Oregon. By 2001, Newbury was too ill to perform. The gathering was cancelled, and the singer died in 2002. The next year, Stamps led the effort to hold a post-mortem gathering in Austin. A small but avid group attended, and Stamps had a mission – make it an annual event and spread the gospel of Newbury. “It relit a fire that hadn’t been there in a while,” Cayce said.

“As soon as Roy started the Newbury gathering, all you heard was about Newbury,” Reid said. “I was like, ‘He’s not Jesus, he’s really not Jesus.’ But it obviously helped Roy get back to where he was before Texas Music magazine crashed.”

Newbury’s family and friends appreciated Stamps’ devotion and grew to love him, regardless of his checkered past. “Roy was the wheel, the heart, and we won’t ever be able to replace him,” Newbury’s mother, Mamie, said shortly after Stamps died. “I loved him like a son. He was smart, he knew the business, he loved Mickey, and he loved everybody that came. Besides that, he was a fighter. He’s been sick a long time, but nobody knew it except the people close to him. He didn’t want anybody to worry about him.”

This past summer, Stamps once again organized the gathering, despite his physical deterioration. By fall, the end was obviously near. Zerre came up with an idea for a “living wake” for Stamps since, after all, “Roy wouldn’t want to miss the party,” she said. The celebration of his life was held in October at his Venus home. Stamps was frail but arose between naps to entertain visitors with stories. Sometime after midnight, with only a few stragglers left, Stamps sat down on the couch next to his turntable and played an album by John Anderson, a country artist he helped promote back in the 1980s.

Next, he played Lee Ann Womack’s new CD that includes the Payne-penned ‘Solitary Thinkin’. The songs reignited his memory bank, and he went on a final tear, reeling off stories in his animated, clipped way of speaking. Wild nights, impromptu jam sessions in his living room, undersold and oversold concerts, drug experimentation – Stamps put a final exclamation point on a story-filled life, paying homage to the musicians he had supported, promoted, and genuinely loved.

“He was a fan of songs and songwriters,” Payne said. “He loved that life and found a way to honor it.”

That same month, Nelson called to invite Stamps to a show at Billy Bob’s Texas, but Stamps was too ill to attend. In November, as he was lying in a Mansfield hospital bed, near death, family members played him a phone message left by Nelson.

“At the end, Willie called him and left him a voice mail and told him how much he was praying for him and loved him,” Reid said. Stamps didn’t respond, at least verbally.

“He cried, but it was a happy cry,” she said. “He was smiling.”