Over the past few years, Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey K. McClendon has been on a wild ride. His company has been one of the largest and certainly the most visible player in the Barnett Shale gas drilling boom here in North Texas and in other shale developments around the country. The Oklahoma native, born, one might say, with oil and gas in his veins, was positioning himself as an environmental activist, using national and regional ad campaigns to promote clean fuel, denigrate dirtier fuels like coal, support the development of the next generation of non-gasoline-burning cars, getting involved in parks, and talking about weaning the United States from its dependence on foreign oil. Gas prices were at record highs, and McClendon personally made Forbes magazine’s list of the richest Americans (his $3 billion ranked him at No. 134 last year).

In many of the places where he’s been active, McClendon has brought the party. He’s given lavishly – to the American Red Cross after Hurricane Katrina, to a couple of colleges. In Fort Worth, Chesapeake has set up scholarships, mounted a breathtakingly expensive ad campaign in support of the Barnett Shale, and purchased one of the most visible buildings in Fort Worth, the former Pier 1 building beside the Trinity River. In West Virginia, where shale was also coming into play, the company announced plans to build an eastern regional headquarters. In California, he gave half a million dollars to a campaign to pass a ballot initiative to provide substantial state funding for alternative-energy vehicles. And he’s rewarded himself as well, not surprisingly – a vacation home here, a pro basketball team there.

But in many ways, McClendon’s spending has brought him no joy – or at least not the love of the populace. In place after place, his projects have caused consternation and fierce local opposition, from big cities to the “gay dunes” on the shore of Lake Michigan. Despite his “green” initiatives, environmental groups have little good to say about him. And when things turn ugly, or the profit possibilities disappear, McClendon takes his bat and ball and goes home, turning out the lights on the party – or on the basketball arena, in Seattle’s case, or the Shale.TV studios here.

Now, as gas prices drop, the profit possibilities are starting to dim for Chesapeake in North Texas and in many ways for McClendon’s fortunes in the gas industry in general. Chesapeake’s stock price, which had re ached about $74 per share in July, dropped steadily through the summer to about $16. McClendon had invested massively in Chesapeake stock, much of it bought on credit, and two weeks ago, his lenders rang the alarm bell. He was forced to sell virtually all of his shares at bargain prices – which may have cost him as much as $2 billion of that $3 billion net worth.

ached about $74 per share in July, dropped steadily through the summer to about $16. McClendon had invested massively in Chesapeake stock, much of it bought on credit, and two weeks ago, his lenders rang the alarm bell. He was forced to sell virtually all of his shares at bargain prices – which may have cost him as much as $2 billion of that $3 billion net worth.

Publicly, McClendon blamed the forced sell-off on the worldwide economic meltdown, but oil and gas industry analysts saw it differently. “They didn’t learn from history,” said Fadel Gheit, managing director of oil and gas research for Oppenheimer & Co., in an interview with an Oklahoma City TV station. “It was a business model based on unrealistic price expectations. Parties don’t last forever.”

So what happens to the Barnett Shale bash here, where the champagne’s been flowing for about three years now? Chesapeake, XTO, and Devon Energy have all said in recent weeks they will ramp down drilling and leasing. Chesapeake spokeswoman Julie Wilson said that $25,000 an acre bonus payments for drilling rights are “a thing of the past.” New bonus figures look to be about $5,000 an acre, if the companies want to drill at all. The company pulled the plug on its online TV talk show, for which it had hired several prominent journalists and begun building a studio.

The glittering all-night gas gala here may turn into punch and cookies in the church basement.

Aubrey McClendon is no rough-talking, cigar-chomping, up-by-his-own bootstraps wildcatter. He is more of an Oklahoma preppy, if that is possible – button-down shirts and nice suits. His college degree is in history, not engineering or geology. He wears his hair a bit longer than most CEOs.

“He is a very delightful and very intelligent guy,” said Bob Willett, associate publisher of Natural Gas & Electricity magazine, based in Houston. “He is easy to talk to, with no pomposity. There is nothing snooty about him. He’s not one of those drilling guys who spent time on the drill bit.

“And he does speak his mind,” Willett said. “I like him because he is honest, but some don’t like that very much.”

The suave exterior is no accident – McClendon was born in Oklahoma City in 1959 to a very rich family. He’s the great-nephew of Robert S. Kerr, former governor of Oklahoma and founder of energy company Kerr-McGee. In fact, Aubrey’s middle name is Kerr.

Kerr-McGee is no longer owned by the Kerr family, but the energy company has had its share of environmental problems, going back decades, to the nuclear fuel plant allegations that formed the basis of the film Silkwood in 1983. Last year, Kerr-McGee spent $18 million on pollution controls at its facilities in Colorado and Utah in a settlement with the U.S. government under the Clean Air Act.

Having plenty of money to start with, McClendon went to college and married more. He met his wife, Katie, when both were at Duke University. Her family had founded Whirlpool Corporation, the home appliance giant, in Michigan. After graduation in 1981, he brought Katie back to Oklahoma and jumped into the oil and gas world.

With childhood buddy Tom Ward, McClendon started out as a landman, scouring Oklahoma for lease agreements, then turning them over to big drillers. It took less than a decade for the pair to decide they’d rather be further up the gas industry food chain.

Chesapeake Energy was formed in 1989 with an initial investment of $50,000. But the company fared poorly. Chesapeake borrowed heavily, and gas prices cratered in the 1990s. By 1998, the stock price was in the $2 range, not much higher than the price the partners got when they took the company public five years earlier.

The turn of the new century brought changed fortunes for Chesapeake, starting in the West. McClendon found a market that other natural gas producers had largely ignored. California and other states had deregulated electric utilities, and new companies were looking for fuel. McClendon convinced Calpine, one of the new California utilities, to produce its electricity using natural gas instead of shipped-in coal. Chesapeake’s sales went up, and so did the price of natural gas, due to the new market demands.

Around this time, the Barnett Shale mother lode began to produce. Geologists had known about the formation since the 1980s, but drillers couldn’t get at it until new horizontal drilling and “fraccing” techniques were developed. Even then, it was expensive, and gas prices had to rise quite a bit to make it economically feasible. McClendon bet that gas prices would go up, and they did (prices hit $13 per thousand cubic feet in July of this year). Chesapeake borrowed heavily, bought lots of property in North Texas, and started leasing as much of the shale as they could.

Not that the shale was McClendon’s only project – or his only controversy.

About 10 years ago, McClendon was jet skiing in Lake Michigan off Saugatuck, a pristine resort town with about 1,200 full-time residents and many more tourists in the summer. McClendon noticed sand dunes on either side of the mouth of the Kalamazoo River where it enters the lake.

He later learned that the land was for sale. Saugatuck residents and Michigan preservationists had long wanted to buy the 412 acres as a preserve. In 2006, they offered the owners $38 million; McClendon offered $39 million and became the new owner.

McClendon wasn’t planning any nature preserve. He wanted to develop the dunes with million-dollar homes, a marina, an equestrian center, and retail. He needed zoning changes to make it happen, and he and his partner have threatened to sue if they don’t get them. Many locals feel that McClendon’s development would change the town substantially, bringing major growth to a town that is happy with its current size.

David Swan, president of the Saugatuck Dunes Coastal Alliance, which is fighting to preserve the dunes, said McClendon got some people mad from the beginning. “We are a very warm and welcoming small town, and after they bought the property, we sent a map of the area and asked Aubrey and Katie if they wanted to come over for dinner,” Swan said. “His attorney responded that they couldn’t do that. He couldn’t even respond on his own. Had his attorney do it.”

Things began to heat up between McClendon and local residents. “Any time we would talk about zoning changes, or compromises on how they might develop the property, he and his lawyers would threaten lawsuits,” Swan said.

Earlier this year, in an article about him in Fortune magazine, McClendon really pissed people off. He called those who wanted to preserve the dunes “completely dysfunctional.”

“It angered me greatly that he would say that,” said Michigan State Sen. Patricia Birkholz. “He obviously has no respect for the people in this area who have been working so hard through the years to preserve this property. And he didn’t understand that the longtime owners of the property have never had fences around the dunes, so it was almost like a public park.”

The property includes about a mile of Lake Michigan shoreline, and state law makes lakeside beaches public for a few yards inland. So McClendon has found himself the owner of the one of the most popular gay sunbathing spots in the Midwest. And often the frolickers don’t wear clothes.

In fact, Saugatuck is known as the “Key West of the Midwest” a popular vacation spot for gays from cities like Chicago and Detroit. The city also has a sizable permanent population of gay men and women. After McClendon bought the property, word circulated that he was anti-gay: In 2004, he had given $625,000 to Americans United to Preserve Marriage, a conservative anti-gay marriage group run by evangelical conservative Gary Bauer in Washington, D.C.

“There was a lot of talk in the gay community about how this guy was coming in and trying to take away the property that the gays had used throughout the years,” Birkholz said. “But McClendon has never addressed those issues. I don’t think he realized that gays are an important part of the social fabric here.”

The previous owners had put a guard shack on the boundary of the southern part of the dunes and charged people $5 to $10 to enter. The fees are still being charged with McClendon as owner.

“He doesn’t want gays to be able to marry,” said Birkholz. “But he will take their money if they want to socialize on his property.”

McClendon didn’t have to go all the way to Michigan to get green-space lovers mad at him; he managed to do that in Oklahoma, around the same time that the Saugatuck fight was shaping up.

In his home state, the debate was over what had been dedicated parkland being sold off by the state – just like Texas officials wanted to do in the Big Bend area with the Christmas Mountains. Created in the early 1940s when the Red River was dammed for flood control, Lake Texoma, with marinas, lodges, and public golf courses, had been the most poular park in Oklahoma.

But in the 1990s, Oklahoma let the park fall into disrepair. Changes in federal law allowed states to sell off parkland to private developers, and Oklahoma figured that private owners would make the investments needed to spruce up the property and bring in economic development. In November 2006, the state sold roughly 1,500 acres for $14 million to the Pointe Vista development group, including partner Aubrey McClendon.

Plans aren’t complete, but McClendon and his partners have said they expect to invest up to $1 billion in the private Pointe Vista development, to include a four-star hotel, hundreds of expensive homes, and a Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course. The site borders land owned by the Chickasaw tribe, and there is talk of building a casino.

“McClendon and his partners have used their influence with state political leaders to get a sweet deal,” said Boyd Steele, who lives in Kingston, Okla., next door to the former park property. “He likes to go on TV and portray himself as Mr. Clean Energy and Mr. Green. But I think that privatizing park land and then making it so expensive that the general public cannot use it is hardly being eco-friendly.”

Stephen Willis, another Kingston resident and president of Friends of Lake Texoma State Park, said they have been unable to even get a meeting with McClendon. “We would expect to get some answers from him on such a big and controversial project. But it just seems to be a dog and pony show. And given all the money [McClendon has] lost recently, you wonder just how they are going to do this project.”

“You would think as a business leader in this state, McClendon would want to use his wealth and leadership to restore this park for the public,” Steele said. “But he obviously doesn’t have the mind-set to do that, but only to make more money. And now he doesn’t have that money. So his next step, I suppose, will be to ask the taxpayers to bail him out.”

McClendon has indeed gotten on the green bandwagon in recent years. He joined with Texas oilman T. Boone Pickens to push for renewable energy as a way to get America away from dependence on foreign oil. But while the two are promoting wind energy and solar power and hybrid cars, they are really pushing for use of natural gas in vehicles and generating plants.

He said in a recent interview that he views his role in environmental issues “as a nice intersection between my moral thoughts about the problem and my economic thoughts about the problem.”

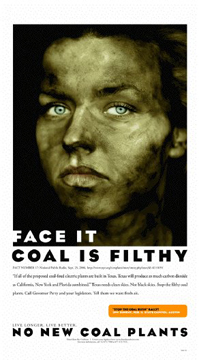

Last year, McClendon financed the Clean Skies Coalition, which ran ads featuring models with smudged faces above the slogan “Face it, Coal is Filthy.” That upset many in coal-mining areas, especially West Virginia. Longtime West Virginia Congressman Nick Rahall called the ads “despicable.” After that, McClendon pulled the ads and made up with Rahall, giving him $3,000 in campaign contributions.

Chesapeake and McClendon have also riled many others in West Virginia. Chesapeake had acquired another energy company in that state in 2005, and with it a lawsuit claiming the company had cheated West Virginia citizens in oil and gas lease deals. When the plaintiffs won in court, Chesapeake was on the hook for $405 million. In response to that, McClendon announced last year that Chesapeake would cancel its plans to build an eastern regional headquarters in Charleston.

“It is one thing to read that West Virginia is the number-one judicial hellhole in America,” he told Mountaineer State viewers in a TV interview. “It is something else to be on the receiving end of what it means to be stuck in that kind of location … So I think we will reconsider our whole approach to where we are going to locate our headquarters building and our people.”

In Texas, McClendon used his “coalition” to lobby hard against TXU’s rush to get 11 coal-fired plants approved by the state. In the end, after TXU was taken over by a private equity group, eight of the 11 plants were canceled.

You might think that joining the fight against “filthy coal” would earn McClendon praise from environmental groups. Not so in California, where Pickens and McClendon are pushing for a statewide measure that would use billions of tax dollars to subsidize the move from gasoline to natural gas in automobiles.

If passed in this year’s November election, Proposition 10 would take $5 billion from the state’s general fund to pay rebates to buyers of alternative-energy cars. But many environmental groups, including the California Sierra Club, oppose the initiative because the rebates favor compressed natural gas (CNG) vehicles over hybrids or fuel cell engines. McClendon has donated $500,000 to the campaign working to pass Prop 10.

“This is a scam, and Aubrey McClendon is a part of it,” said Jim Metropulos, a senior advocate for California Sierra Club. “This one is very self-serving, and he is just looking at this as an investment. And they want the public to subsidize the big payoff they might get.”

Metropulos pointed out that rebates for CNG cars would be $10,000, and trucks would get $50,000. Hybrids and other alternative energy cars would get just $2,000. Metropulos also said that CNG carbon emissions are only 10 percent less than gasoline-powered cars, and the state already has a plan in place to reduce carbon emissions from vehicles by 25 percent by the year 2020.

“It is all about a business deal for them,” said Richard Holober, executive director of the Consumer Federation of California, which also opposes Prop 10. “Pickens has an interest in running the fuel stations that CNG cars will need, and McClendon has the natural gas they want consumers to buy. The environmental benefits of this plan are very small, but the possible economic benefits for them could be very big.

“This state has a budget shortfall right now, and if this passes, education and social programs will have to be cut, because this money will come out of the state’s general fund.” Holober said. “When there is money to be made, you wear whatever camouflage suit you need to cover up the truth. These days, McClendon and Pickens are wearing the green suits.”

McClendon’s focus on the bottom line doesn’t mean he’s stingy in other ways. In fact, he gives away lots of money. He donated $1 million to the American Red Cross after Hurricane Katrina. He has given more than $16 million to his alma mater, Duke University, and more than $12 million to the University of Oklahoma. When the Duke lacrosse team faced accusations of rape (later dismissed), McClendon spent $500,000 to buy newspaper ads praising the players and defending them against the allegations.

He spreads around plenty of money in the political arena as well, though it’s hard to tell what the contributions say about his political beliefs. Since 1990, according to the Federal Elections Commission, he donated $873,850 to federal politicians and political action committees.

McClendon has said that more use of natural gas will combat global warming, yet he is an ardent backer of Oklahoma U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe, who calls global warming a hoax. He backs the only openly gay Oklahoma politician, Jim Roth, for a seat on the state board that oversees the oil and gas business, yet he supports a ban on gay marriage.

In 2004, he contributed $250,000 to the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, which ran a questionable campaign against presidential candidate John Kerry. In this presidential election season, however, he has given the maximum amount each ($2,300) to Barack Obama, John McCain, Hillary Clinton, Rudy Giuliani, Bill Richardson, Mitt Romney, and Tommy Thompson. It’s called hedging your bets, not unusual for corporate CEOs.

Getting a read on McClendon’s personality is as difficult as figuring out his politics. He wields lots of power in Oklahoma, and finding acquaintances who will talk about him on the record is tough. “He’s always been driven by his ego,” said an Oklahoma lobbyist who worked for McClendon for more than a decade and didn’t want his name used. “He doesn’t settle for compromises on any issues, be they political or economic. But I could see changes in him as his company got more successful. There was a certain arrogance, especially as he got more into politics.”

The lobbyist said the Swift Boat and anti-gay marriage contributions were a part of that. “Aubrey wanted to get more known nationally, and in 2004, the conservative power folks were telling him what to do,” the lobbyist said. “He really didn’t think the public would take notice, and I don’t think he cared much either. He wanted the country to use more natural gas, and he contributed to any politician who would help him do that.”

Last April, McClendon made another donation, but not voluntarily. The National Basketball Association fined him $250,000 for comments he made about moving the Seattle Supersonics to Oklahoma City.

Until Hurricane Katrina hit, McClendon had not been known as a major basketball fan. But after that storm, the New Orleans Hornets made Oklahoma City their temporary home, while New Orleans recovered. McClendon and two partners, Oklahoma City businessmen Clay Bennett and Tom Ward – both billionaires, both friends of McClendon’s since grade school – tried unsuccessfully to buy the Hornets. But the idea of owning a big-time pro sports franchise had stoked their egos. They went shopping for a team and reached an agreement with the Seattle SuperSonics owner to purchase that team in 2006.

From the beginning, the new ownership group assured Seattle fans that the team would stay there. And like most team owners, they wanted tax money to refurbish Key Arena, to the tune of $300 million. Negotiations with local and state officials continued into this year.

But while the other Oklahoma City-based owners were publicly saying the team would stay put, McClendon let the truth out. In an interview last April with The Journal Record, an Oklahoma City business publication, McClendon said, “We didn’t buy the team to keep it in Seattle, we hoped to come here. We know it’s a little more difficult financially here in Oklahoma City, but we think it’s great for the community and if we could break even we’d be thrilled.

“To the great amazement and surprise of everyone in Seattle,” he said, “some rednecks from Oklahoma, which we’ve been called, made off with the team.” To the amazement of Seattle political leaders, McClendon made that statement while negotiations were still going on.

“It was almost like this billionaire boys’ club from Oklahoma City came into Seattle and used brute force to get what they wanted,” said Steve Pyeatt, founder of Save Our Sonics and former member of the King County Council. “They just repeatedly lied about their intentions. Ironically, though, it was McClendon who told the truth.”

Pyeatt said that McClendon’s political contributions were a factor in negotiations on public arena funding. Seattle has the second-largest gay community in the U.S. and tends to lean more Democrat than Republican.

“When it came out that [McClendon] had given so much money to the Swift Boat and the anti-gay marriage group, it made a lot of people roll their eyes,” Pyeatt said.

“The way I look at it, [McClendon and his partners] wanted a Rolls-Royce and we were offering a Porsche,” Pyeatt said. “So they said the hell with all of you and took the team away. It didn’t matter to them that this team had been here for 41 years.”

The former SuperSonics were renamed the Oklahoma City Thunder. The team begins play at the Ford Center later this month. And, no surprise: McClendon and his partners are negotiating to have the Oklahoma City arena upgraded at taxpayers’ expense.

When companies like Chesapeake began buying up Barnett Shale leases three or four years ago, they started in the hinterlands. Rural acreage came fairly cheap, starting out at $400 an acre in bonus money. But as the drillers moved into urban areas, neighborhood associations began banding together to get higher prices and, in some cases, more environmental and safety restrictions. Over time the lease prices shot up; some deals were worth $27,000 an acre.

Things seemed to be going quite well for Chesapeake. In July, its stock was selling at its highest point ever, and natural gas prices were at a peak as well. Over the last several years, the CEO added Chesapeake stock to his portfolio at an amazing rate. From September 2002 thorough April 2008, McClendon bought more than 11 million shares at a cost of approximately $319 million. Then from April to June of this year, he added another 2.45 million shares.

But those were mostly bought on borrowed money. When the stock was trading in the $70 range in July, the lenders didn’t see a problem. McClendon had sold the investment community on the notion that natural gas was a big play, with the shales providing the huge growth. The country was going to use more and more natural gas, McClendon said, and Chesapeake was going to produce it.

In the natural gas business, however, what went up eventually came down. Analysts figure that, in today’s market, a “sweet spot” (highly productive) well can be profitable even when natural gas is selling as low as $5 per thousand cubic feet, but there are not many of those around. The less-productive wells can make money only when gas prices are at $7 to $9. With natural gas prices around $6.50 now, companies are taking a huge risk to sink any more wells.

The drillers have only themselves to blame: Gas prices are low because companies like Chesapeake have put so much product into the market, without any real increase in natural gas usage. In short, McClendon bet the farm with his own stock purchases, but the nation did not suddenly start driving around cars that use compressed natural gas (CNG).

The Wall Street meltdown, therefore, was only part of the problem when the lenders woke up two weeks ago. They immediately applied the financial thumbscrews, forcing McClendon to sell off most of his stock at prices far below what he had paid for much of it. His 31 million shares, worth about $2 billion last July, were then worth about $570 million. He sold all but about $50 million worth to pay off the loans.

McClendon wouldn’t talk to the Weekly for this story. When his margin call sale was announced, he issued a statement placing the blame on the Wall Street woes. He was “very disappointed to have been required to sell substantially all of my shares of Chesapeake” because of the “worldwide financial crisis.” The sale, he said, didn’t reflect his view of Chesapeake’s future performance potential. “My confidence in Chesapeake remains undiminished, and I look forward to rebuilding my ownership position in the company in the months and years ahead,” he said.

The Oklahoma lobbyist said it should be interesting “to see how he pulls Chesapeake and himself out of this. After you lose all that money in such a short time, well, the average CEO might never be able to get up again. But I wouldn’t count him out. His ego won’t let him lose.”

McClendon’s ego aside, Chesapeake is being forced to pull back. Seems that his personal stock-purchase loans weren’t the only ones causing worries. The company itself also has a debt problem, according to some experts.

Chesapeake has announced it will stop buying property and doing most new leasing deals. It is selling off assets (about $12 billion in the next year) to put itself on more solid footing. Chesapeake has already sold off $6 billion in property and lease deals in several other shale areas of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas.

The company held a two-day conference for financial analysts last week at its Oklahoma City campus, and McClendon was quite upbeat. “It is going to be an exciting couple of months as we bring to fruition these various deals we have been working on,” he said. “Apparently there is a great deal of skepticism in the marketplace about our ability to do it, and that is a big motivator, and has been for me for the past 19 years.

“So, I think there will be lots of newsworthy events on the positive side out of the company over the next couple of months, so I just ask you to stay tuned,” he said.

Financial analysts think it is too early to tell how the market will treat energy companies like Chesapeake. “One big winter storm and the gas prices will shoot up,” said John Baen, a real estate professor at the University of North Texas, and an expert in oil and gas leases and pipelines. “But a company like Chesapeake has a lot of questions. They have to get through some short-term debt problems, and they need to sell off a lot of assets to get the cash flow right. But they have been through these cycles before, so I would expect them to get through their current problems.”

John Olson also sees Chesapeake’s debt as a problem right now. Olson, co-manager of Houston Energy Partners, an investment company specializing in oil and gas companies, said Chesapeake has a 60 percent ratio of debt to capital. By contrast, XTO Energy’s ratio is 47 percent, and Devon Energy’s is just 14 percent. “The amount of debt they have is too high,” Olson said. “The near term is going to be tough, but the long-term outlook is much better. The problem is they have to cross a pretty big desert before they get to the water.”

And what happens in North Texas while Chesapeake negotiates that desert? Beyond the precipitous drop in bonus money and the slowdown in drilling, a lot of local folks are worried about the effects on well and pipeline safety, for instance, when companies start cutting corners – especially when they don’t have a lot of faith in the CEO’s “green suit.”

Virtually everyone interviewed for this story – from California Sierra Club officials to the Michigan save-the-dunes crowd, to fans of the Lake Texoma parkland – have said the same thing: McClendon uses the “green” banner for his own purposes, especially in national advertising campaigns, but abandons it on the local level.

“You cannot just do that on the national stage and avoid the local issues,” said Cathy Hirt, founder of the Fort Worth-based CREDO (Coalition for a Reformed Drilling Ordinance). “If Aubrey McClendon wanted to be the leader in green technology for drilling in this country, his company would be doing those things without being forced to.” Instead, she said, “they seem to fight everything – from how close they can drill to homes to polluted water injection wells to using diesel trucks to haul equipment and pollute the air. It’s almost as if they are using environmental issues as an advertising gimmick and then ignoring them as they drill here.”  Tolli Thomas, president of the Southwest Fort Worth Alliance (a coalition of neighborhood associations), saw Chesapeake’s attitude toward environmental issues when her group assessed leasing contracts for homeowners. “Chesapeake was just less willing to discuss issues in the lease that affected the neighborhood and community the most,” she said. The neighborhood association signed a deal with Vantage Energy last month.

Tolli Thomas, president of the Southwest Fort Worth Alliance (a coalition of neighborhood associations), saw Chesapeake’s attitude toward environmental issues when her group assessed leasing contracts for homeowners. “Chesapeake was just less willing to discuss issues in the lease that affected the neighborhood and community the most,” she said. The neighborhood association signed a deal with Vantage Energy last month.

“We wanted air quality monitors on their equipment and compressor stations no closer than 1,000 feet from any home,” Thomas said. “We also wanted the gas to be odorized when it was practical to do so and limits on truck traffic. Vantage was willing to do those things, but Chesapeake was not.”

Greg Hughes, a neighborhood activist in the TCU area, said the financial health of a company like Chesapeake has to be put in context as the city re-examines its drilling ordinances. “In five years, we may have new owners of the infrastructure and the wells. All of this might be passed down to weaker companies, and we may be dealing with a range of reliability and problems,” he said. “Deferring maintenance may be a way for them to better their bottom lines.

“When all these energy companies came to Fort Worth,” Hughes said, “no one really understood the full cycle of natural gas. No one mentioned pipelines, but now we are seeing that as a big issue. They say it will be good environmentally for the country to use more natural gas, but we see a big environmental downside on the production end. They say how great it is that our buses use [CNG], but they don’t even use their natural gas for the trucks they use.”

Corsicana attorney Glenn Sodd, who has negotiated oil and gas leases, thinks pipeline safety and maintenance could become a very ugly issue. “Doing them right is more expensive than doing them wrong,” he said. “When you cut corners in rural areas, there is less of a safety issue. But in crowded neighborhoods, the danger from leaks and explosions can go up dramatically.” And it’s an issue the city hasn’t dealt with adequately, he said.

Pipelines are regulated by federal and state laws, but Gary Hogan, a vocal member of Fort Worth’s Gas Drilling Task Force, said local political leaders need to challenge some of those regulations before serious accidents happen. “Two years ago, the drilling companies never mentioned pipelines or the eminent domain laws they used to acquire property,” Hogan said. “I think Chesapeake in some ways did not step up to the plate as other companies did in addressing pipeline and environmental issues.”

“Maybe this downturn is a good thing for Fort Worth,” he said. “The Barnett Shale leasing has been a runaway train for a very long time. Maybe now we can take a step back, take a deep breath, and look at the issues better and with more study.”

In Oklahoma and California and Michigan, West Virginia and Texas, local citizens say they’ve had worrisome experiences with McClendon. When he didn’t get what he wanted from them, they said, he frequently canceled the party.

So who knows what the Barnett Shale fandango will look like in these parts in a year or two. Could be champagne, could be cheap beer. Could be a folded tent. Aubrey McClendon says to stay tuned.