In Texas, shrubs may be the among the first victims of global warming. It’s a twist that might have pleased Molly Ivins.

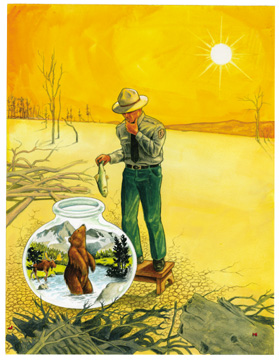

The shrubs in question are the squat, bushy piñon trees that populate the scrub forests of Big Bend National Park, and if the escalating, permanent Southwest heat wave that climatologists are predicting comes to pass (or, in reality, fails to pass off), the piñons – like many other native plants and animals spread across the still-wild parts of this country – may see their current habitat transformed into something that they cannot survive. What can a concerned West Texas park ranger do to postpone a massive forest die-off? Get out the chainsaw, maybe.

The shrubs in question are the squat, bushy piñon trees that populate the scrub forests of Big Bend National Park, and if the escalating, permanent Southwest heat wave that climatologists are predicting comes to pass (or, in reality, fails to pass off), the piñons – like many other native plants and animals spread across the still-wild parts of this country – may see their current habitat transformed into something that they cannot survive. What can a concerned West Texas park ranger do to postpone a massive forest die-off? Get out the chainsaw, maybe.

“We can’t water them. So how can you reduce the stress on trees in a forest? One way is to reduce the number of trees competing for a limited amount of water available,” said Craig Allen, a U.S. Geological Survey forest ecologist who has studied Southwest piñon forest die-backs. At the Padre Island National Seashore near Corpus Christi, the problem is likely to be rising seas, gradually creeping up the 50-foot-tall sand dunes that now protect inland wildlife. “We would lose habitat. Animals would have less room to roam,” said Mark Biel, a National Park Service resource management specialist at Padre Island. “We have white-tailed deer, coyotes, gray fox, numerous shore birds, grassland bird species, white-tailed hawk, peregrine falcons” – and some of those could be threatened.

So has the government prepared a pre-emptive convoy of earthmovers to haul in more mountains of sand? “No, it’s something we pretty much let take its course,” Biel said. In deep East Texas, the question is whether the bald cypresses of the Big Thicket can survive long-term climate change – and if they can’t survive in those deep swamps, how do you move a bunch of huge trees and the complex, rare ecosystem surrounding them? In the California mountains, giant sequoia saplings aren’t reacting well to the warming of the Sierra Nevada range. Do the park rangers there install sprinkler systems around gargantuan trees? And what about the craggy island paradise off the California coast, where in the last three years, an unusual number of one bird species’ chicks have died? Rising sea temperatures have rearranged ocean currents, sweeping away from the Farallon Islands refuge the waves of tiny sea organisms known as krill, that the adult birds feed to their young. It’s the worst result that biologists have seen in 35 years of studying the species, known as the Cassin’s auklet. But to try to save the dying chicks, said one of the biologists, would be unnatural – and unscientific.

With global warming, Texas shrub-huggers and swamp rangers, California bird biologists, and a host of other conservators of this country’s indigenous plants and wildlife are having to rethink the don’t-mess-with-Mother-Nature stance that has been the basis of their work for more than 40 years. As the Earth itself begins to change, it’s turning the concept of natural preservation on its head. In the age of global warming, public-land managers across the country are coming to realize they face a stark choice: They can let national parks and other wild lands lose their most cherished flora and fauna – the critters that, in many cases, are central to the park or national forest’s identity and mission. Or they can become gardeners and zookeepers on a massive scale.

Thus far, they’ve done almost nothing – and recent reports suggest that many of them don’t even understand the looming problems. But in other places, scientists and environmentalists are beginning the awesome task of figuring out the science behind what might be needed and how to accomplish it. In one case, an environmental group is already buying land to use as refuges for warming-displaced species. In another, the science of species survival is being studied on the site of a project originally sponsored but long since shed by a Fort Worth billionaire. Since the 1960s, the idea that natural preservation consists mostly of letting nature take its course – absent manmade environmental disturbance – has been doctrine in the vast landscape of public parks bureaucrats, biologists, environmentalists, rangers, and others involved in preserving America’s natural environment. When naturalists have intervened to save species, as in the 40-year struggle to save the bald eagle, their efforts have been driven by the goal of returning life to its wild state, so that a damaged ecosystem can tilt back into balance.

With global warming, however, this hands-off approach is rapidly becoming quaint and out-of-date. As the planet grows hotter and the consensus mounts that the temperature is not going back down, there may be less meaning in the idea of preserving “naturalness.” After all, in the not-too-distant future, the state of nature in many cases may be something nobody’s ever seen. And in fact, public-lands managers have been under orders for seven years to begin to deal with this problem. In January 2001, just as Bill Clinton was handing the White House keys to George W. Bush, the Department of the Interior issued a broad order to the federal agencies that manage one-third of the nation’s surface land as well as numerous marine sanctuaries. The order was at once simple and fiendishly complex: The agencies should “consider and analyze potential climate change effects in their management plans and activities.”

It was a reasonable directive. Already, millions of acres of forests in Glacier National Park have fallen to a beetle infestation apparently linked to climate change. The seagrass meadows, mangroves, oyster reefs, and other wetlands life of the Mission Aransas Reserve in southeast Texas are under threat of rising seas, which could introduce saltwater pests such as shipworms and barnacles into freshwater ecosystems, where they unsettle the natural balance. Higher seas also could undermine the cleansing and flushing action performed by wetlands, possibly increasing pollution and damaging or driving out even more native species. At the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, coral reef bleaching – a phenomenon that, if prolonged, will undermine the area’s marine ecosystem – may be connected to warmer sea temperatures. On the 2.6 million acres of U.S. land managed by the Bureau of Land Management in northwestern Arizona, a recently intensified cycle of drought, wildfire, and flooding has caused desert scrub and cactus to be replaced by grasslands.

So far, however, public-land managers have responded by doing almost nothing, according to a new report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the agency that evaluates federal programs. By and large, the GAO says, officials who manage U.S. public lands have simply ignored the 2001 directive. However, the GAO report, released last summer, also notes that land managers were provided no guidance of any kind on how to deal with climate change – nor did they attempt to deal with the problem on their own. Since 2001, of course, these federal departments have been ultimately directed by George W. Bush, who has famously not concerned himself with climate change. But the GAO report and interviews with National Park Service scientists and managers around the country strongly suggest that government stewards of wildlife and public land simply don’t understand the problems they face in an era of climate change.

“Resource managers we interviewed … said that they are not aware of any guidance or requirements to address the effect of climate change, and that they have not received direction regarding how to incorporate climate change into their planning activities,” the GAO report said. And in fact, the Department of the Interior itself seems unclear on the very concept of addressing the effects, rather than the causes, of climate change. In its official response to the GAO report, an associate deputy secretary answered the criticism that the agency has “made climate change a low priority” by, essentially, changing the subject. In its response letter, the park service official bragged on the agency’s development of “renewable energy resources; improving energy efficiency and the use of alternative energies at our facilities across the nation.” No word about any successes in protecting parks, forests, and rangeland from global warming’s effects.

“Resource managers we interviewed … said that they are not aware of any guidance or requirements to address the effect of climate change, and that they have not received direction regarding how to incorporate climate change into their planning activities,” the GAO report said. And in fact, the Department of the Interior itself seems unclear on the very concept of addressing the effects, rather than the causes, of climate change. In its official response to the GAO report, an associate deputy secretary answered the criticism that the agency has “made climate change a low priority” by, essentially, changing the subject. In its response letter, the park service official bragged on the agency’s development of “renewable energy resources; improving energy efficiency and the use of alternative energies at our facilities across the nation.” No word about any successes in protecting parks, forests, and rangeland from global warming’s effects.

This is no minor failure. An emerging scientific consensus says that unless the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, state fish and game departments, and private environmental organizations re-direct their missions to deal with climate change, they’ll oversee the advance of nationwide environmental catastrophe. The character of public wild lands will be drastically and permanently altered. The managers of America’s natural resources deserved the GAO’s scathing critique. But there are roadblocks beyond bureaucratic intransigence that keep naturalists from effectively grappling with global warming’s effects. Though researchers have identified some species and ecosystems already threatened, science is mostly ignorant of climate change’s impacts. Until recently, there was little experimental research in the field.

For instance, there is no scientific answer yet to questions as basic as how much heat or dryness it takes to kill a tree or whether foggy coastal and less-foggy inland California will become warmer or cooler due to global warming.

Beyond the lack of scientific data is a fundamental philosophical problem: To preserve public wildlife during a time of significant climate change, managers will have to do things that run counter to the current ethic of “natural preservation.”

“Conservation and land management agencies like the park service are confronted with a collapse of the paradigm they’ve operated under, which is [that] the future will be more or less like the past, and nature needs to be managed only on the margins, where we correct for the minor injustices humans inflict on the natural environment,” said David Graber, chief scientist for the Pacific West region of the National Park Service, whose office is at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park. “We’re facing a period of dramatic uncertainty. What ‘managing nature’ would mean is a dramatic unknown. We don’t know what our goals would have to be. We’re literally talking about things that have only been talked about for months, rather than years.” Global warming undermines almost all the rules that environmental stewards have lived by.

With a warming planet, invasive species are no longer merely exotic pests that hitch passage from other continents. They’re native grasses, shrubs, beetles, bacteria, and viruses that are simply moving to higher ground, so to speak – spreading to new “native” habitat opened for them courtesy of higher average temperatures or rising seas. The millions of acres of forests in the northern U.S. that have been recently killed by pine beetles, which now thrive in the region’s recently warmer winters, are another apparent testament to this emerging phenomenon. “The west side of the park used to have much colder winters, which slowed the beetles. But winters for the past 15 or so years have not been as cold,” said Judy Visty, natural resource management specialist at Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. “Pine beetles are wreaking havoc.”

Fire and drought are two other heightened, intertwined threats. In the Western U.S., they have become something more significant than mere components of a historic cycle of life. Scientists now predict that escalating droughts, tree die-offs, and fires could cause Western forests to contribute more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than they extract. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration precipitation models, western Texas may be as much as 10 percent drier by the year 2100 than it is now. A 2002-2004 drought has already wreaked shrub Armageddon on 2.5 million acres in the Four Corners area of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, though it largely spared piñon scrub forests farther east in places like Big Bend National Park – for the time being. “We know that that amount of climate stress was enough to push many species over their level of tolerance,” said Allen, the USGS forest ecologist.

Research into California’s giant sequoia indicates that with warmer average temperatures, these monarchs of the forest may slow and then stop producing seedlings. And “if the fog or the ocean currents were to change, [the coastal redwood] would be in real trouble,” said Ken Lavin, interpretive specialist at Muir Woods National Monument just north of San Francisco. Other global warming-induced changes not yet as noticeable as forest die-offs are still troubling. Mountain lakes are disappearing along with the glaciers at Montana’s Glacier National Park. The pika, a cool-weather-loving mountain rodent, is vanishing from the Sierra Nevada. Rising seawater threatens to salinize the freshwater ecosystems of the Everglades and submerge beach habitat along the Northern California coast. And an increasingly hot and dry climate is projected to kill 90 percent of the namesake plants at Joshua Tree National Monument.

For most people, these events are the canaries in the ecological coal mine, portending the far-off day when climate change may have life-and-death implications for humanity. For conservationists, however, these embattled plants and animals and others like them are the coal mine. “It may be that soon one-third of the species I’m seeing outside my window might not be able to find habitat here. Maybe half of them will be new species that find the new climate here amenable,” Graber said. “Am I going to fight the new species? Am I going to welcome them?” The questions are agonizing for naturalists, professionals whose reason for existence, for nearly a half-century, has been preserving native species and fighting invasive ones. They and the entire environmental movement are left with unnatural choices: They can intervene aggressively to maintain habitat threatened by planetary warming – installing sprinkler systems around California’s giant sequoias, to name one suggestion floated by scientists. In the process they would become something akin to farmers and pet fanciers.

They can create huge migration paths northward for heat-threatened plants and animals. They could transport to Illinois or Wisconsin the seeds from bald cypress growing in East Texas swamps, nudging along an inevitable northward habitat shift. They could mobilize fleets of bulldozers to fight seawater intrusion on coastal prairies in southern Louisiana and Texas. Or they can decide to continue to use the traditional hands-off approach – and thereby allow millennia-old ecosystems to die off and be replaced in ways that would never have happened naturally, if not for global warming. Graber and others believe that, whatever the answer turns out to be, conservationists need to be thinking hard about such unthinkable questions – and doing it now.

Preserving wild spaces and wild things as close as possible to the ecosystems that existed before civilization arrived hasn’t always been the accepted mission of naturalists. New York’s Central Park and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, for example, are horticultural fabrications, with scant relationship to the natural world that came before – and yet locals seem to like them just fine. In fact, a different idea, that of trimming nature into a pleasing aesthetic spectacle, drove park management well into the 20th century. Then, in 1962, the Secretary of the Interior set up a special advisory board on wildlife management, led by ecologist A. Starker Leopold, to consider what America’s parks should be. The board came up with a revolutionary idea, summarized in a pamphlet known universally in the nature bureaucracy as the Leopold Report. It is best known for five evocative words summarizing what became the American consensus: Each nature preserve should be “a vignette of primitive America.” “It instituted in the park service a kind of respect for nature that was apart from gardening,” Graber said. “Before the Leopold Report, I called it cowboy biology. We made it up as we went along. If Yellowstone wanted more buffalo, they got it.”

Preserving wild spaces and wild things as close as possible to the ecosystems that existed before civilization arrived hasn’t always been the accepted mission of naturalists. New York’s Central Park and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, for example, are horticultural fabrications, with scant relationship to the natural world that came before – and yet locals seem to like them just fine. In fact, a different idea, that of trimming nature into a pleasing aesthetic spectacle, drove park management well into the 20th century. Then, in 1962, the Secretary of the Interior set up a special advisory board on wildlife management, led by ecologist A. Starker Leopold, to consider what America’s parks should be. The board came up with a revolutionary idea, summarized in a pamphlet known universally in the nature bureaucracy as the Leopold Report. It is best known for five evocative words summarizing what became the American consensus: Each nature preserve should be “a vignette of primitive America.” “It instituted in the park service a kind of respect for nature that was apart from gardening,” Graber said. “Before the Leopold Report, I called it cowboy biology. We made it up as we went along. If Yellowstone wanted more buffalo, they got it.”

Under the new regime, it became necessary to prove that such a bison introduction would be “natural.” Any meddling that occurs in protected areas now must be in the service of a perceived previous natural order. Notwithstanding some controversies – such as “natural” wolves versus “introduced” ranchers in the Yellowstone area – this approach has achieved monumental success. Nearly a century after U.S. Rep. William Kent introduced the legislation that created the National Park Service, the 295-acre ravine he donated to create Muir Woods National Monument remains much as it was a millennium ago, filled with redwoods, ferns, and ladybugs. “We don’t move anything unless it falls on someone,” said Lavin, the Muir Woods interpretive specialist.

Another impressive legacy of the new ethos lies 20 or so miles to the west of Muir Woods. At the turn of the century, egg hunters and pelt gatherers had reduced the wildlife-rich Farallon Islands to a relatively barren state. However, since they became protected as a national wildlife and wilderness refuge in 1969, the islands have become the largest seabird colony outside Alaska and Hawaii. Northern fur seals, which once populated the Farallons by the tens of thousands, were hunted to extinction there following the Gold Rush. They, too, have returned in force. A single pup was born on the islands in 1996. Last year, there were 100 pups. The starving Cassin’s auklets, however, suggest that this let-it-be strategy may be a luxury the wildlife can no longer afford. But strategies that could actually save species from climate-change disaster are hard to come by.

Decades of research show that warming trends in the central Sierra Nevada, about 250 miles southeast of San Francisco, are taking their toll on saplings of the giant sequoia. So do officials in Sequoia National Park build greenhouses? Or do they prepare a new habitat farther north, removing other species to make space for sequoia saplings? Should such moves even be contemplated, given the still-fledgling nature of predictive climatology? And what of the rest of the trees in the West, the ones doomed to die from drought, fire, and beetle infestation? Scientists studying forest die-backs say one response might be to thin the forests, so that individual trees are hardier and more beetle-resistant. In Texas, a version of this is already taking place, albeit on private land. The state government has paid ranchers atop the Edwards Aquifer under Uvalde, Medina, Bexar, Comal, and Hays counties to chainsaw cedar and mesquite trees on their land. By eliminating these thirsty root systems, ranchers “increase water yield” from the aquifer, said Rob Jackson, a Duke University professor of environmental sciences.

Nor is it just humans and trees that could benefit from increased water supplies, Jackson said. The Edwards Plateau is host to many of the state’s endangered species, such as the blind salamander, the golden-cheeked warbler, and the black-capped vireo – a pinkie-sized songbird. While this Texas chainsaw tree massacre might seem like serious environmental meddling, the reality – as with most of this ecological debate – is more complex. The timber harvest can actually be seen as an effort to restore the ecosystem that existed in the Hill Country before 1850, when overgrazing and farming turned prairies into cedar- and mesquite-covered scrub land. Other ideas generating ambivalent response from natural preservationists and federal land managers include intensive breeding and genetic engineering to create insect-resistant tree species, combined with the aggressive use of herbicides and pesticides on the invading beetles.

Wildlife managers have long believed that local plant species should be kept genetically pure. But climate change may ultimately call for a sophisticated type of wildlife gardening, in which heat-loving Southern plant species are brought north and encouraged to crossbreed with cold-loving cousins. The massive die-off of piñon trees in the Southwest is being called a “global warming type event.” Again, selective logging such as the Texas-funded culling program in the Edwards Plateau might be one answer, some scientists say: If fewer trees share scarce water, they just might survive in the new climate. But for plant species that simply can’t survive in their old habitat, some scientists are floating the idea of a forced march north.

Animals whose habitat dwindles as the climate changes might just scurry elsewhere, explained Nathan Stephenson, a research ecologist at the Western Ecological Science Center at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. But trees cannot get up and walk away. “The National Park Service has to decide: Are we going to assist species migration?” he said. Another bit of environmental meddling with Texas habitat would do just that. It involves helping Texas and Louisiana’s vast bald cypress swamps transport themselves northward as the local climate becomes too hot for survival – by simply driving some seedlings north. “The bald cypress tree’s seeds are dispersed in the water. They disperse in the direction the water is flowing. I don’t anticipate they could move very well northward” – unless humans intervene, said U.S. Geological Survey plant ecologist Beth Middleton. She has spent years studying the health of bald cypress in swamps at the extreme edge of their range.

After a career spent puttering about alone in swamps measuring leaf piles, Middleton came across a monumental inference: With global warming, the cypress swamps of Texas might not be long for this earth. Middleton’s years of research show that bald cypresses actually do best in places like Arkansas and Kentucky and not nearly as well in the hotter southern portion of their range, including Texas. As Texas gets hotter, she believes, bald cypress in Texas and the swamps they live in might get scarcer. She’s been working with the federal government’s natural preservation bureaucracy in hopes of getting money for bald cypress research here. “The species of trees can’t necessarily get there on their own. And if you helped them, there’s the question of ‘Would they survive there?’ This is just talking right now. It’s very difficult to get funding for projects like that,” Middleton said.

Helping plants and animals migrate north isn’t just a matter of mailing seeds or leasing fleets of nursery trucks. Many species under threat aren’t easy to dig up and put in a pot. Soil microorganisms, fungi, butterflies, and other small creatures critical to the functioning of ecosystems may also find their traditional homes unlivable. Assisting species migration would mean setting aside broad swaths of wild land to provide an uninterrupted pathway north for entire habitats.

“I’ve had a number of conversations with land managers, identifying all the land in California that could conceivably be used as [refuges] and what would be the appropriate species to go where. The magnitude of the problem is mind-boggling,” said Graber, the park service scientist. “There is a vocal minority of people in the conservation community who believe that things should unfold on their own. The theory being, we don’t know what we’re doing, and we’re bound to screw things up. “What we’re talking about is an order of intrusion greater than anything we’ve done in the past.”

Already the nonprofit Nature Conservancy is considering buying land and ecological easements to create north-south habitat-migration superhighways. “We need to take into account this vulnerability to large vegetation shifts,” said Patrick Gonzalez, a forest ecologist who works with the Conservancy as a “climate change scientist.” Doing this on any sort of meaningful scale, however, would require making the preservation of American grasses, trees, and rodents an expensive national priority. And it would mean treating habitat-choking urban sprawl as even more of an environmental calamity than is currently recognized. Putting America on this sort of ecological wartime footing – to prepare for an environmental future that nobody can fully predict – will likely prove a hard sell in Washington. Almost as difficult will be convincing the environmental community to abandon a hard-won national consensus about what it means to preserve the natural world.

The bureaucracies that manage public land already have to answer to myriad bickering constituencies. Some of global warming’s greatest impacts will appear without warning, as complex changes in ocean temperatures, currents, and growing seasons cause cascading effects. Combating these effects might mean quickly deciding, say, to fortify Padre Island’s beaches and sand dunes with bargeloads of sand, to keep rising sea levels and worsening storms from wiping out nesting beaches used by endangered Kemp’s ridley turtles. Saving species in such a quickly changing environment may not allow for policy meetings, comment periods, revised management plans, and alternate implementation strategies. It might just mean deciding at a moment’s notice to mash up buckets of krill stew and spoon-feed auklet chicks – now and forevermore.

But moving with speed means acting from some scientific basis. And in the realm of predicting specific effects of climate change on particular groups of plants or animals, the science is scarce. Although there are reams of conclusive science on the “whether” of global warming, there’s very little precise information on when and where and what will happen next. Before park officials begin loading ferns onto flatbeds or launch the mother of all tree-thinning operations in the Colorado Rockies, they need scientific backing to be sure what they’re doing has some hope of success. Despite the vast swath of death wrought across the West by drought, heat, and bark beetles, science still doesn’t know exactly what it takes for nature to kill a tree. At Muir Woods, for example, there’s no record whatsoever of a mature redwood dying a “natural,” non-human-induced death. “I think one of the big challenges of planning is the amount of uncertainty. We don’t even know if it’s going to get warmer and drier or warmer and wetter, and if you don’t even know that, it starts to get really hard,” said Stephenson, the USGS forest ecologist.

Brad Wilcox, professor of ecosystems science and management at Texas A&M University, said global climate change does not equal global drought. “People are predicting what they call more extreme events” – more Katrina-level storms, for instance. “When we do get rainfall, it might get more prolonged or more intense.” It’s hard to talk about making an ecosystem resilient if you don’t know what it takes to kill it in the first place. Science is just now getting down to the brass tacks of cooking and parching trees to death on purpose – in a recently re-purposed 500-ton welded stainless-steel-and-glass habitat (and now, habitat oven) once owned by Fort Worth billionaire Ed Bass. The oven used to be known as Biosphere II, an artificial enclosed ecosystem originally intended for research on what it would take to reproduce an Earth ecosystem in space. The University of Arizona recently agreed to lease this giant terrarium near Phoenix from its current owner, a land developer. The university will rededicate Biosphere II for research on how organisms react to climate change.

Finally, scientists will be able to write an accurate recipe for baked tree. “Wow, that [must] sound like a really dopey experiment,” said University of Arizona natural resources professor Dave Breshears, a faculty member of the Institute for the Study of Planet Earth. “But we don’t really have the right kind of quantitative information. We’ve got a drought, and we’ve got bark beetle infestations … and warmer temperatures. And it’s hard to unravel the effects of those.” Understandably, many scientists still believe that a decision to abandon the old approach to natural preservation is a mistake. Eric Higgs, director of the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, fears land managers may wreak havoc if they begin meddling with, rather than preserving, wild habitat.

“How is it we find respectful ways of intervening, of removing invasive species, or planting or translocating species? How do we do that in our deeply respectful way?” Higgs wondered aloud. “We want future generations to say, ‘They didn’t get it all right, but they got some of it right.’ Leopold certainly made many mistakes, but he was an individual who kind of had it right. I’d like to think that contemporary restorationists would blaze that kind of trail.” With that in mind, National Park Service trailblazers across America are meeting to figure out how to incorporate climate change into a scheduled revision of overall park policy. The park service has created a Task Force on Climate Change to figure out what, if anything, to do about threatened park resources.

The agency has sidestepped some of what’s at stake, however. When asked what the park service is doing to preserve wild lands in the face of global warming, the agency’s climate change coordinator boasted of a program called Climate Friendly Parks, which seeks to reduce parks’ carbon footprint by doing things like installing low-flow toilets. Addressing the threat to ecosystems by reducing parks’ resource consumption is like treating a cancer patient by telling her to cut back on food additives. Scientists are well aware of this apparent lack of direction in the agency’s response to climate change.

“There’s kind of a chaotic feeling right now. Everyone understands the situation is really problematic. We need to start. We can’t wait to act until things start dying,” Graber said. “But we don’t know what to do.” Leigh Welling, the park service climate change coordinator, puts it a different way. “It’s a scary thought,” said Welling, “Managers … are saying, ‘Oh jeez, how do I do my job?'”

A version of this story first appeared in High Country News. Illustrations by John Kastner