After years of debate and controversy, Congress and the Bush administration still haven’t produced new immigration policies. And so for those looking north, the official face of the United States is Homeland Security. And the wall. Those looking south often see Mexico through a haze of anti-immigration rhetoric about a “broken border.” They don’t realize that the border in Texas isn’t broken, it just bends and sways, like the river – and the adaptable people who define it. The killing of a Redford teenager a decade ago by U.S. Marines slowed the pace of militarization of the border, but 9/11-inspired fears, a generous dose of racism, and a redefined national police force known as the Border Patrol have brought the machinery of low-intensity conflict back with a vengeance.

After years of debate and controversy, Congress and the Bush administration still haven’t produced new immigration policies. And so for those looking north, the official face of the United States is Homeland Security. And the wall. Those looking south often see Mexico through a haze of anti-immigration rhetoric about a “broken border.” They don’t realize that the border in Texas isn’t broken, it just bends and sways, like the river – and the adaptable people who define it. The killing of a Redford teenager a decade ago by U.S. Marines slowed the pace of militarization of the border, but 9/11-inspired fears, a generous dose of racism, and a redefined national police force known as the Border Patrol have brought the machinery of low-intensity conflict back with a vengeance.

Now, Homeland Security is securing land for more than 150 miles of wall along Texas’ part of the border. Even though Congress specifically vetoed plans to make it part of a wide security corridor, the wall still will effectively redefine the U.S. border, leaving farms, wildlife refuges, and parts of towns in a no-man’s land south of the wall, disrupting lives, livelihoods, and ways of life going back well beyond the American Revolution. Arrogant tactics have produced official opposition from cities, environmental groups, and many others along the route, not to mention lawsuits that actually have a chance of affecting the project. So for several weeks, I followed the wall and visited with those who call the river home. They are very, very worried.

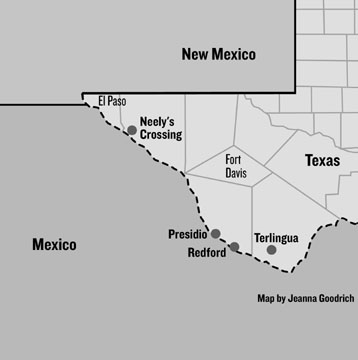

The place is called Neely’s Crossing, but it is really nowhere, 40 miles downstream from El Paso. A quiet river, an earthen berm, sun, and wind. My guide for the day steps over a barbed wire fence and heads to water. Here the view of the Rio Grande is clear, but above and below us it slinks away behind stands of voracious salt cedar and mesquite and stout lines of elegant river cane. In the adjacent wetlands and salty flats, a lone set of cattle tracks leads into deep brush and to El Rio. Two years ago, this spot was scene to a brief but dramatic standoff involving what appeared to be a Mexican Army outfit assisting a marijuana shipment across the river. The crew rode in machine-gun-equipped humvees, observed from this side by an assortment of seriously outgunned U.S. Border Patrol agents, Hudspeth County deputies, and Texas state troopers. While no shots were fired, a stranded humvee was set on fire in the river by the retreating smugglers.

That event made Neely’s Crossing someplace as far as the feds were concerned. In response, a 4.6-mile-long fence up to 18 feet high and capable of withstanding the assault of a 10,000-pound vehicle moving at 40mph is going up. Border wall ambitions, launched by the U.S. Secure Fence Act of 2006, have set Homeland Security bosses into a frenzy of land seizures and lawsuits as they try to wall across Texas. Besides the few secluded miles of fencing here, there will be 6.2 miles of wall sandwiching the Presidio port of entry and another 120 miles from the east side of Big Bend National Park into the Rio Grande Valley.

Following the river for an hour along Ranch Road 192, we have crossed paths with only one other traveler, a local farmer. Bill Guerra Addington is taking me to see the farm his family leases farther downstream, part of which they will lose if the proposed wall takes root. But he has something else in mind first. As we approach Indian Hot Springs, a sacred site now in private hands, near what was once the home of the region’s most renowned curandera, a dog rushes the car in a blizzard of barking. I can just make out a black hat and a gesture above the rise beside us as we pass the first house we’ve seen.

“Go ahead and stop here,” Bill says. As I kill the engine, the dog turns and pads away, and we’re soon standing before three rock-pile graves crested with dark wooden crosses. The remains of Buffalo Soldiers reside here, black Union troops utilized in the war on the native Apache more than a century ago. Other graves lie lower on the hill.

Carefully, a mounted cowboy crosses the arroyo to look us over. I relax only after I see he didn’t bother to fill his rifle case before packing over. He recognizes Bill – naturally. Addington has had a hand in every fight worth fighting in these lesser-known reaches of Texas. First there was the defeat of the proposed Sierra Blanca nuke dump that cost him his marriage, then the fight against heavy-metal-laced New York City sludge, during which an arsonist burned down the family lumberyard. Now we have the wall. Like families across these western reaches of serpentine greenery – a section of El Rio known locally as The Forgotten River, stretching from here southeast to Lake Amistad on the other side of the Big Bend – the vaquero straddles two worlds. He has homes on both banks. He runs cattle on both sides. His wife is a Mexican national. When I ask his name, he stumbles. Do I want his gringo name or what he goes by? “Whichever you prefer,” I say. “The name you use.”

The man with hands shaped and swollen by work, a leather cowboy hat, and black pearl-snap shirt introduces himself as Eddie Roberto Raymundo. We’re to call him Mundo. If the wall comes here, he says, he’ll slip over to Mexico, where there is more freedom. “I just don’t go along with putting this fence up,” he says. “When you’re living on the Rio Grande and they’re just right next door to you, what’s the problem of going over to his home to eat or him coming to your house to eat?” Then, with quintessential Mexican hospitality, he invites us to his house. He brags on the “no chemical” Mexican chicken being pulled from the pit. Not like what you get in U.S. supermarkets, he says. As we talk about walls and fences and neighbors, Mundo, who can’t read or write, sums up in a phrase the sentiment of the dozens of river residents I will meet this week.

“Nothing’s really perfect,” he says, “but our freedom should be perfect. Your freedom should be a perfect thing.”

With the sun submitting to the hills, we retrace our way to town. Knowing we have tripped untold numbers of buried ground sensors, we’re expecting a green-and-white “Migra” escort as soon as we’re on blacktop, and we’re not disappointed. After the flashing lights in the rearview comes the routine interrogation: Where have we been? What were we doing? It helps to have a local resident and celebrity activist in the car. We’re on our way even as backup arrives. Back in Sierra Blanca, we pull up alongside Bill’s neighbor, a sheriff’s deputy in orthopedic shoes, dark shorts, and undershirt. He nearly spits when we mention the wall. “It won’t do a thing,” he says. “It’s a joke.” Even if a fence were the solution, what good is an obscure 4.6-mile-long barrier floating on 2,000 border miles?

Bill argues that the ecological solution – removing the dense salt cedars that suck millions of gallons from the river while increasing its salinity – could also be the security solution. Their removal would offer law enforcement extended sight lines, making the area easy to patrol. The river, an icon of the American West, faces other challenges. A decade ago, researchers found 26 toxic chemicals in its lower reaches and pegged the area downstream from El Paso as particularly tainted and no longer swimmable. State regulators determined that drinking the water or eating the fish could lead to health problems “over the course of a human lifetime.” Of course, river residents for untold lifetimes have made this river their supermarket – and more. Mud and reeds are used for building materials. Firewood is gathered in the winter. Healing and ceremonial herbs are still sought out in these parts. However, with the fences on the way, a new attitude about how close is too close for U.S. citizens is on display at the river, and immigration sweeps have been stepped up.

Bill argues that the ecological solution – removing the dense salt cedars that suck millions of gallons from the river while increasing its salinity – could also be the security solution. Their removal would offer law enforcement extended sight lines, making the area easy to patrol. The river, an icon of the American West, faces other challenges. A decade ago, researchers found 26 toxic chemicals in its lower reaches and pegged the area downstream from El Paso as particularly tainted and no longer swimmable. State regulators determined that drinking the water or eating the fish could lead to health problems “over the course of a human lifetime.” Of course, river residents for untold lifetimes have made this river their supermarket – and more. Mud and reeds are used for building materials. Firewood is gathered in the winter. Healing and ceremonial herbs are still sought out in these parts. However, with the fences on the way, a new attitude about how close is too close for U.S. citizens is on display at the river, and immigration sweeps have been stepped up.

The Forgotten River is discovered again when it connects with the channeled Rio Conchos at the “junction,” or La Junta de los Rios. If it weren’t for the healthier Conchos flowing from Mexico, the Grand River would never make it to the grapefruit fields of the Rio Grande Valley. Likewise, if it weren’t for Ojinaga, the larger, economically humming Mexican town I’m about to enter, Presidio, on the U.S. side, would be a much poorer place. You can see the relationship best at night, when Presidio (population 4,200) practically expires and the burning lights of 20,000-population Ojinaga shine clear as tangled starlight. The fields here have been farmed for thousands of years – it is thought to be the oldest continuously cultivated spot in North America. These days, however, many of the Presidio fields are going fallow. Presidio County Commissioner Carlos Armendariz drives me through his 700-plus acres along the river. Homeland

Security hopes to place 3.1-mile stretches of fencing along the levee above and below the Presidio port of entry. With it will go a chunk of the Armendariz farm. Both the city council and the county commissioners here have passed resolutions opposing the wall. Everyone I speak with believes it is an insult to their friends, families, and neighbors across the bridge. Still, it’s not one of the issues being debated in any of the contested local elections. “What can we do about it?” asks Armendariz, who is facing a challenge for his post. He reminds me that Congress gave Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff startling powers under the Real ID Act, including legal support to override such inconveniences as the Endangered Species Act and virtually any other federal law that stands to slow the progress of the fence. “It’s like you put a hundred-dollar bill in my pocket,” Armendariz says. “You may say, ‘Give it back,’ but you put it there, and I’m going to spend it.”

Not so many years ago Carlos and his brother Louis grew 200 acres of melons and 200 acres of onions in this alluvial soil. Their payroll fluctuated from $5 million to $7 million each year. As many as 400 farmhands would cross the river directly into the fields (some with temporary worker permits, some without), work for the day, and maybe head to the grocery or gas station before returning home. Getting paid by the crate or sack, the workers earned well above the federally mandated minimum wage, Carlos says. Over time, increased scrutiny of their paperwork began to reduce the number of laborers willing to cross. Pretty soon, the brothers found themselves without a workforce. “They went on to California and New York. Why? Because immigration was enforcing this law here but not out there,” Carlos insists.

Now the brothers plant alfalfa, a crop they can cultivate and harvest on their own with some aging farm equipment. Vast sections of their land have been taken over by brush. “Fences don’t make friends,” his brother Louis says. “Good relations, respect, is the best wall that anybody can have.” Good relations between residents and the many federal agencies here have been hard to maintain through the years. There are many reasons, but none as obvious as what happened in Redford in 1997. You can blame the bullet, or the shooter, or the victim, but most folks here will tell you that bureaucratic ignorance was to blame for the U.S. Marines in night-vision goggles and bush suits. They came to hunt drug runners in this sleepy river town. Instead, they shot and killed a beloved high school student.

Herding goats near the family home on an unremarkable night, Esequiel Hernandez had no reason to believe he was being observed by anything more dangerous than a curious coyote or a rabbit when he shot into the brush with his granddad’s .22 rifle. But the 18-year-old’s bullet was answered by a hidden patrol that had been tracking the boy for more than 20 minutes. The killing was a national scandal. Troops were pulled out. Grand jury investigations were launched. And local Redford residents went to testify in Washington, D.C. For a while at least, as the federal attorneys finished working out their $2 million settlement with the Hernandez family, things did quiet down. Lately, however, surveillance has increased dramatically, locals say – just as it did before the shooting.

Up a dusty drive and past chicken coops and fenced gardens, I find Father Mel, the area’s former circuit-riding priest. On most Sundays, until he retired a few years ago, Father Mel La Follette would put 200 miles on his truck, serving congregations up and down both sides of the river. As part of the Redford Citizens Committee for Justice, he was with the delegation that spoke with then-drug czar Barry McCaffrey and a raft of congressional types. In his home, Father Mel has satellite radio news playing and C-SPAN muted on the tube. Like most of those still living in Redford, he has become more politically engaged since the shooting. “I don’t know how long they had Marines hiding before they shot somebody, but there was a definite change in tone, and then they shot, they shot our boy,” he says. Given the briefings the Marines received, the shooting was almost inevitable, he believes. “They come in with all their weapons and have been told that everybody here is a drug dealer and it’s a hostile population and nobody can be up to any good. … They also were told people often use a herd of goats to shield their illegal activities,” La Follette says.

With Homeland Security and the Border Patrol now preparing to secure what amounts to a new border along a proposed fence line a hundred yards from the actual international boundary at the river’s center, police actions have increased. The arrest of one Redford man on charges of making a terroristic threat – because he tried to shout a Border Patrol agent off his land – doesn’t sit well with locals. A series of immigration sweeps around the Terlingua ghost town on the edge of Big Bend National Park, about 50 miles downriver, chafes, too.

The raids remind residents of the period of conflict that began in 2002 when the Border Patrol shut down a string of “unofficial” crossings up and down this region, and immigration raids included dark helicopters overhead and unpleasant scenes below.When it comes to all things border, residents of the interior and the people they elect are “so totally out of touch, they might as well be from Mars,” Father Mel says. “Even some of the people who live farther up in Texas don’t know what they’re talking about.”

The raids remind residents of the period of conflict that began in 2002 when the Border Patrol shut down a string of “unofficial” crossings up and down this region, and immigration raids included dark helicopters overhead and unpleasant scenes below.When it comes to all things border, residents of the interior and the people they elect are “so totally out of touch, they might as well be from Mars,” Father Mel says. “Even some of the people who live farther up in Texas don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Across the street at the post office, Rosendo Evaro, a lifelong Redford resident, chats with me in the afternoon sun. “I tell you, in my whole life, in 75 years, there was only one congressman that came over here, him and his wife, shaking hands with every family, to every house, and that was Congressman [Richard] White. At least he got an idea if we had pigs or chickens or what, right? But in Washington? Shit, they don’t know nothing. They say that all Presidio County is nothing but bootleggers.” He laughs, but it is obvious he is troubled by the pain that implemented ignorance has caused. “Since they are big shots, everybody believes them. But … this is the most peaceful place on earth.”

Evaro suggests that the Border Patrol operates as the Texas Rangers did decades ago. “Same way Texas Rangers would kill Mexicans 100 years ago so the checks would keep coming, that’s the way the Border Patrol does their job.” It’s not just memories of old injustices against Mexicans that fuel resentment here. Some are also those awakening to earlier, indigenous identities. Roberto Lujan pulls an O’Doul’s from the cooler. The lights from the port of entry, from Ojinaga, blaze on the dark horizon as we lean against the vehicles in the carport. Lujan’s grandfather came from a pueblo not far from here, across the river. He worked the mercury mines of Terlingua before gravitating north to Alpine. When Roberto entered school, the town was still segregated. The only Anglos he met before the schools finally merged in 1969 (a full 15 years after the Supreme Court ruled “separate but equal” was illegal) were the white special-ed students who for whatever reason were shipped south to Hispanic Centennial School. As Lujan’s family has splintered and spread across the country, he is the only one who has returned to the border.

His study of family history has helped him embrace his roots as a Jumano Apache. That in turn has given him a new perspective on the military forts that spawned towns such as Fort Hancock, Fort Davis, and Fort Stockton. He calls them the “extermination camps of indigenous ancestry.” “Now we have Border Patrol posts. They’re very reminiscent of what we had back then. It’s like to keep people on the Rez,” he says. “You literally have to check out of here on Highway 118.” Of course, the same goes for any of the northbound roads from here. The flashing lights of the checkpoints mean you must stop. You must declare your citizenship. Typically, you are also asked where you are coming from and where you are going.

It’s up to the officer where those questions stop. Then you are either on your way, allowing a search of your vehicle, or, if you refuse the search, settling in for a long wait on a search warrant. For veterans like Lujan, it’s insulting. “We’re not criminals. We’re traveling on a highway that was paid for by our tax dollars,” he says. Meanwhile, the Border Patrol is working to hire 4,000 new agents, whose first posting will be the American Southwest, their mission no longer principally drugs and illegal immigration but hunting terrorists. Recruitment brochures call this borderland the “front line on the war on terror.” Unfortunately, there are thousands of river residents who live on that front line. And for many, the worst terrors they’ve seen have come from within.

At the end of my first week on the road, I leave a Border Patrol helicopter circling west of Marathon, passing one white Ford after another marked by the green stripe of La Migra. For a hundred miles it seems, they patrol the endless lines of barbed wire paralleling Highway 90. In Langtry, population 30, residents are skeptical of promised benefits of the wall and fearful of federally threatened seizures of private property. In Del Rio, a woman who works closely with immigrants seeking citizenship laments the changes she has seen across the border. Already it has become increasingly difficult to get papers, much less find a path to citizenship. “Sometimes I feel sad. I think, ‘Oh, my God. This is my country. This is what we’ve become.'” said Diana Abrego of La Clínica de Inmigración. “We know Mexico needs to fix its economics, and the United States has a lot to do with that, but unless they work that out, they can put up all the walls they want and nothing will happen.

“Where there is work, there is a way.”

Even as some counties have begun to strike agreements with Chertoff for walls masquerading as flood control, here – as in most of the state – officials have already seen a decrease in border traffic from a stronger Border Patrol presence. Even without the wall, arrests of river crossers have collapsed in sector after sector across the state, while they have increased in San Diego, the sector with the nation’s first southern border wall. In the Del Rio sector, apprehensions decreased 46 percent in fiscal 2007 and 38 percent the year before that, according to agency statistics. Likewise, the Rio Grande Valley posted a 34 percent decrease last year. The vast majority of drug runners breaching the southern boundary come through official ports of entry.

In fact, the most convincing argument against Homeland Security’s plans for mile after mile of fences is the success of the Border Patrol – and the failure of Homeland Security’s own proposals. Chertoff and Co. swept into the Texas borderlands with a storm of lawsuits, seeking to quickly amass the land it wanted for 700 miles of proposed fencing. The aggressiveness of that effort, and the howls of protest it invoked, inspired U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison and U.S. Rep. Ciro Rodriguez to push through an amendment requiring Homeland to work more amicably with property owners. That created the political landscape that transformed a proposal for double fences more than a football-field’s distance apart, with security roads and stadium lighting, into a single 18-foot structure – the new “discrete” walls being proposed around official ports of entry in towns like Del Rio, Eagle Pass, Laredo, and Roma.

Homeland hopes to fence a total of 370 miles this year. Chertoff recently announced that some fence sections could be replaced by high-tech surveillance measures – a “virtual” wall. However, as he was uttering those words, the U.S. Government Accountability Office was announcing that the $20 million Arizona pilot high-tech project, spearheaded by Boeing, is plagued with problems that will take at least three years to correct. Critics charge Homeland with failing to work with Border Patrol in the first place.

Homeland hopes to fence a total of 370 miles this year. Chertoff recently announced that some fence sections could be replaced by high-tech surveillance measures – a “virtual” wall. However, as he was uttering those words, the U.S. Government Accountability Office was announcing that the $20 million Arizona pilot high-tech project, spearheaded by Boeing, is plagued with problems that will take at least three years to correct. Critics charge Homeland with failing to work with Border Patrol in the first place.

Chertoff has acknowledged that Boeing’s surveillance system works only in “certain types of terrain.” The lingering question, the unanswered question, is the most obvious one of all: Do walls work? A Congressional Research Project report updated last summer found that while fencing did reduce traffic in some areas, “there is also strong indication that the fencing, combined with added enforcement, has re-routed illegal immigrants to other less fortified areas of the border.” Areas like the unforgiving Sonoran Desert in Arizona, where hundreds of determined immigrants die each year. Borderwide, deaths are approaching record highs.

In a nation increasingly hobbled by massive war debt, the Congressional Research Service last year estimated the price of fencing and maintaining the entire southern border for 25 years at $49 billion – labor and land acquisition not included. Even if the larger wall project collapses with the presidential election, as many expect, Eagle Pass Mayor Chad Foster believes his city – the first Texas city sued by Homeland for allegedly denying the agency access – will be walled. “The point is, we don’t feel that Texas needs physical barriers,” Foster says. “The border of Texas is midstream of a very well-defined river. Anytime we move off of that midpoint, we’re ceding land back to Mexico.”

As they exist today – and they change often, usually with little time for public comment – plans for the wall would slice through college campuses, nature preserves, and innumerable family properties. They also run through Eagle Pass’ city park – the site, ironically, of International Friendship Day festivities, where residents of booming Piedras Negras and Eagle Pass convene each year to celebrate their common history. “Our fathers and forefathers fought to secure the Texas border,” Foster says. “Now our own government is giving property back to Mexico. We have an issue with that. With modern technology we can put a smart bomb down a stovepipe, and you’re telling me we cannot secure the Texas border with technology?”

Eagle Pass opposed the wall from the start. Foster supported an early Border Patrol proposal that included eradicating the river cane and building better patrol roads around the port. However, the 10-foot-high “decorative fence” that went along with the package was anathema. A follow-up meeting led him to believe that Customs and Border Protection agencies would agree to delete the fence. Still, two of the five council members voted against it. “They flat out said, ‘We don’t trust them,'” says Foster. After the Hutchison amendment, the city wrote Homeland several times requesting a meeting but received no response. Homeland then sued the city to take 131 acres by eminent domain for a “permanent easement,” putting up $100 for compensation.

Entering the Rio Grande Valley, I soon discover an island of familial memory increasingly encroached upon by high-dollar suburban sprawl to the north and federal eminent-domain threats to the south. Living on the remains of vast tracts granted to their ancestors by the Spanish crown in 1767, the families of Granjeno can trace kinship to one another by counting back a few fathers on this hand, a grandmother or two on the other. Through the years, the original grant of up to 18,000 acres has been whittled down to a mere 75. (“We didn’t know we had rights,” one elderly resident tells me.) So when the federal government came seeking permission to enter property here to stake out a proposed border wall, all but a few refused. With the government tight-lipped, residents had to fish for information. “We never knew what they were going to do, because apparently the Department of Homeland Security is very secretive,” says Reynaldo Anzaldua, a former Customs agent who is fighting to protect his property.

Though the families were here before the signing of the Declaration of Independence and weathered the Mexican War of Independence, the Texas Revolution, and the U.S.-Mexican War, they still find themselves having to prove their right to exist. After Reynaldo was quoted in the Los Angeles Times saying, correctly, that, “We didn’t come to the U.S. The U.S. came to us,” one anonymous e-mailer ridiculously urged him to “Go back where you came from.” If any U.S. community is where it came from, it’s this one. It is the border that keeps shifting. Granjeno resident Gloria Garza drives me over the levee that backs up to her property and onto a second levee overlooking the Rio Grande. Between the two are several hundred yards of empty fields. Were the fence up today, we would be a levee away from what would effectively become the new southern boundary of the United States.

Homeland’s proposed fence stops at a bridge under construction on the west side of Granjeno. To the west, no wall is proposed for land owned by Dallas billionaire and Bush family confidante Ray Hunt, compounding local bitterness. Across the valley, communities are under siege. While Homeland’s environmental impact statement says the agency needs 508 acres for 70 miles of planned fence, nowhere does it state just how many square miles of U.S. territory will be locked on the other side – an abandoned no man’s land. Though they still don’t welcome the wall, folks here tend to feel they have dodged a bullet. The original alignment of double fencing would have sliced their properties in half, or worse. Today, the proposed 60-foot swath will affect them, even steal a couple of houses, but it is an improvement, they say. Flood lighting may be intrusive, but more property would be preserved intact.

Still, Reynaldo worries about more guns coming to this area. A relative of his still hunts from time to time in the wide-open fields to the south, he says. Occasionally there are arguments with Border Patrol agents, when one side or the other will “get feisty.” “You get somebody like Blackwater down here – they’re likely to shoot him,” Reynaldo says. It’s not an unfounded fear. Blackwater USA has been lobbying hard for a contract to train the thousands of new border agents approved by Congress. Regardless of the amount of land taken by the government, one severe impact remains the same – that on the river itself, already one of the world’s most endangered waterways. Increasingly, the “Great River” no longer has the strength to pass beyond the sand dunes announcing the Gulf of Mexico.

Through the years, the far-reaching palm forests that greeted Spanish ships five centuries ago at the river’s mouth have been reduced to 134 paltry acres pampered in private preserves like the one operated by Max Pons. “Sabal palms made great wharf pilings,” he tells me. “They can last for hundreds of years. They don’t deteriorate.” After The Nature Conservancy purchased the site in 1999, Pons was brought on as caretaker. However, in coming months, Homeland Security plans could evict Pons from his personal Eden. Along with him would go the rare palm wilderness and thick scrubland, home to numerous endangered animals like the jaguarundi and ocelot, as well as several farms and homes between the International Water and Boundary Commission’s levee and the river. “We’re trapped,” says Sonia Najera, South Texas program manager for the Conservancy. “We’re trapped between the river and the wall.”

Both the Conservancy property and a 557-acre Audubon Society holding will fall south of what would, in effect, become the United States’ new southern boundary. “We can’t see a way to operate our center if [the wall] goes up,” said state Audubon Executive Director Anne Brown. “I think it’s a lot for people to expect that that we would be able to open it and have staff in this kind of unsecured zone.” Those 1,500 acres would not be the only Texas land behind the wall. For decades, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has channeled $100 million in taxpayer money into a string of some of the most biologically diverse wildlife areas in the nation. As much as 40,000 of the agency’s current 88,000 acres could be lost to the wall, I’m told.

An environmentally based suit to stop wall construction in Arizona’s San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area served only to demonstrate Homeland Security’s powers. A district judge ruled in favor of Defenders of Wildlife and the Sierra Club last October, but a provision tucked inside the Real ID Act allowed Chertoff to waive 19 federal laws – including the Endangered Species Act – to get on with construction. So far, in the dozens of land-grab lawsuits Homeland has brought against Texas residents, cities, and schools, only one person has had the courage to sue the feds in return: El Calaboz landowner Eloisa Tamez has since been joined by a neighbor, won a small victory in federal court, and become a symbol of indigenous and Texan resistance to the wall. Tamez is used to fighting for her rights, including fighting Anglos who told her, as a teen, that she didn’t need a high school education. Today, the associate professor at UT-Brownsville holds a doctorate in health education.

Tamez, of Lipan Apache and Basque descent, worries about the social cost of the wall. “This is an indigenous culture that has been here for generations,” she said. “It seems to me this is going to become a war zone. We are going to be chased away. We’re going to become extinct.” Two weeks ago, the condemnation suit brought against Tamez for denying Homeland Security access to her land hit a snag. U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen in Brownsville agreed with Tamez that “negotiations are a prerequisite to the exercise of the power of eminent domain.” Hanen found that Homeland had presented no evidence that it had ever tried to negotiate with the professor before going to court and denied the agency’s request for an expedited order condemning her land. However, should the sides not reach an agreement, Hanen did not agree that a jury trial was in order. At that point, an appeal may be necessary, said Peter Schey, Tamez’ attorney and executive director for the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law. His motions for a preliminary injunction and class-action certification have yet to be heard.

“If it delays it until [Chertoff’s] out of office and others can look at this wall business more seriously and the advisability of it, then so be it,” Schey said. “I think by next January officials will be looking at this whole wall project through a new lens.” In the last few weeks, Pons says he has encountered two jaguarundis on the Conservancy tract. The palm forests and Tamaulipan brushland offer premier habitat for ocelots, too, though he’s never seen one. Fewer than 50 of the cats are believed to remain in the nation – all in fragmented pockets of Valley wilderness such as this. “You can’t restore a river as long as people have no connection and no relationship to it,” says John Horning, executive director of WildEarth Guardians, a longtime player in the fight to protect the river’s headwaters region. “I actually think where the border wall is going to be – yards, tens, hundreds of yards distant from the river – its primary impact won’t be ecological, but it will be more cultural and social. What happens in that dark zone that no one penetrates, the public won’t care about. “To actually create physical barriers” to the Rio Grande, he said, “is essentially the final nail in the coffin of a river that’s struggling to stay alive.”

This story was adapted from a series that first appeared in the San Antonio Current, written as Greg Harman traveled the river. The series, plus videos and a blog, are at www.murodelodio.com.