In October 2004, when Tarrant County College District officials posed at a ceremonial groundbreaking for their downtown campus along the Trinity River bluff just east of the Tarrant County Courthouse, Chancellor Leonardo de la Garza called the project an architectural masterpiece. He said it would cost $135 million and predicted that students would be cracking open books there by this year.

If those predictions were answers on an exam, de la Garza would be heading for a failing grade. Four years later, the 38-acre project, by far the most ambitious ever undertaken by the college system, is only 15 percent complete. Costs are now estimated at more than three times the original figure. Two buildings – including, strangely for a college, the library – have been erased from plans, and college officials will no longer even predict a finish date. “We have decided not to announce a firm completion date at this time,” Vice Chancellor David Wells said last week.

If those predictions were answers on an exam, de la Garza would be heading for a failing grade. Four years later, the 38-acre project, by far the most ambitious ever undertaken by the college system, is only 15 percent complete. Costs are now estimated at more than three times the original figure. Two buildings – including, strangely for a college, the library – have been erased from plans, and college officials will no longer even predict a finish date. “We have decided not to announce a firm completion date at this time,” Vice Chancellor David Wells said last week.

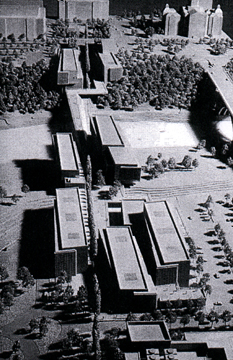

But the project’s troubles go deeper than even those details suggest. The campus that the chancellor described in such glowing terms, with its sunken plaza and underground walkway, its strangely angled buildings rising on both sides of the river, and elaborate bridge spanning the river, has drawn the opposition of downtown business leaders. A key permit from the Army Corps of Engineers – which must be granted if the campus is to be built as planned – has never even been applied for. Near the site where Fort Worth was founded, an enormous hole the size of two buildings has been gouged out of the bluff and filled with concrete . Local historians and state historic preservation officials are up in arms over the fact that the college has ignored the recommendations of historic preservation experts, destroyed buildings before their historic value could be assessed, made the major cut in the bluff – and still has not filed for the required permit. The college is being forced, belatedly, to do an environmental assessment that should have been done before the first shovel of dirt was turned – and that may or may not satisfy the Corps. The project has been plagued with major technical glitches, design changes, and escalating construction costs. And more than $40 million worth of property on both sides of the river has been taken off the city’s tax rolls by the district’s land purchases.

What’s more, some community leaders – including one of the people responsible for the college district’s creation – are questioning the need for such a costly project. “This time I’m out to stop this campus,” said oilman Larry Meeker, who was chairman of the steering committee set up in 1965 to sell the taxpayers on the need for the college. About $200 million of the $350 million that the downtown project is expected to cost should be used instead for scholarships and other educational needs, he said – “What we don’t need is an expensive monument to administrators’ egos.” And just as he roamed Tarrant County gathering signatures on the petition to create the college 43 years ago, he is now telling everyone who will listen that they should join him in opposing the project. “Putting hundreds of millions of dollars into concrete and a giant hole in the ground instead of into kids and teachers is unconscionable,” he said. “It’s the college to nowhere, a boondoggle,” said attorney Robert Gieb, who resisted selling his office building on East Bluff Street until he was threatened with eminent domain. Gieb is angered over the amount of prime downtown property that the college has taken off the tax rolls to build what he calls the “Taj Mahal on the Trinity.” TCC could have taken a couple of downtown blocks and built a functional college campus, he said. “Taxpayers ought to be outraged … It says a lot about the educational thinking of these folks that they have taken out the library to save money but have kept the chancellor’s office on top of the hill.”

Internal documents and e-mails obtained by Fort Worth Weekly under Texas’ open records act confirm many of the critics’ charges. And they also show that even the college district’s normally compliant trustees are getting restless. They have told de la Garza and Wells to start looking for alternatives if costs continue to climb. Despite such misgivings, however, the board handed over $10 million from the district’s $22 million contingency fund last week to keep the project alive.

Ultimately, it may not be up to the trustees to decide the project’s fate. One former Corps official said he believes the continued – though much delayed – construction work, without federal permits, may have put TCC in violation of federal law.

If it set out to do so, TCC couldn’t have picked a construction site in Fort Worth with more emotional and legal strings attached to it. The site sits on the edge of what’s left of one of the city’s most historic neighborhoods, near Cowtown’s original townsite, where soldiers built the fort looking out over the river bottoms. It affects the sight lines to the iconic old courthouse and the historic Paddock Street Viaduct. Because of the planned new bridge over the Trinity River, the cut in the bluff, and the location of more than half of the project on the levee and the low plain north of the river, the project could significantly affect the environment, flood control, and the sacred cow of the Trinity River Vision project.

By federal law, any project that could permanently modify a levee, affect the flow of floodwaters, dump pollutants from dredged material into a navigable waterway, or result in the demolition of historic sites must receive a permit from the Corps. Such projects require the applicant to do an environmental assessment under the National Environmental Policy Act. When historic properties are involved, the National Historic Preservation Act also kicks in, requiring not only an environmental study but historical and archeological investigations by the Corps, working with the state historical commission.

In this instance, the levee itself is considered historic because of its contribution to Fort Worth’s development, said Joseph Murphey, historic architect with the Corps’ Fort Worth office. Altering it, he said, will change its historical context. And dropping piers deep into the levee for the bridge and building foundations could permanently damage its integrity. But in spite of the laws that have been on the books for more than 40 years that govern such projects, TCC has not applied for such a permit.

In areas under its authority – such as the north bank of the river – the Corps has the legal power to stop a project that has not received the necessary permits. However, college officials have argued – successfully up to this point – that because the only work being conducted thus far is on the south side of the river and out of the Corps’ control, no permit is required for that part of the project, and the agency is powerless to shut down construction.

The Texas Historical Commission, on the other hand, has recommended for three years that the project be stopped until it has gone through the rigors of the federal permitting process. But while the state agency does have jurisdiction, it has no enforcement power. “We act only in an advisory capacity,” said executive director Larry Oaks. THC did have limited jurisdiction over the historic bluff on the south side of the river under the Antiquities Code of Texas, he said. But by the time the agency became aware of the project, he said, “the bluff was already gone. … There is no way to rectify that damage. It would be prohibitive. … All we can do is hope to find a compromise” to keep more damage from occurring.

The Texas Historical Commission, on the other hand, has recommended for three years that the project be stopped until it has gone through the rigors of the federal permitting process. But while the state agency does have jurisdiction, it has no enforcement power. “We act only in an advisory capacity,” said executive director Larry Oaks. THC did have limited jurisdiction over the historic bluff on the south side of the river under the Antiquities Code of Texas, he said. But by the time the agency became aware of the project, he said, “the bluff was already gone. … There is no way to rectify that damage. It would be prohibitive. … All we can do is hope to find a compromise” to keep more damage from occurring.

The Corps is in a Catch-22 of its own making, said Kip Wright, a former historical architect with the Corps. Technically, he said, the college isn’t in violation of a permit, because there is no permit to violate. “Whether this fiasco is a result of ignorance or a deliberate attempt to circumvent the law in order to get the project under way,” Wright said, “TCC is in violation of federal law.” Murphey said that when the Corps became aware of the scope of the TCC project in 2005, it initiated a historical assessment on its own, in consultation with THC. The Corps then required the district to do the environmental assessment, which has delayed work on the north part of the campus. “We are doing the [review] process as it was meant to be implemented” by law, he said.

While that process goes on, work on the southern half of the site – the downtown side – has continued, albeit slowly.

If TCC’s environmental assessment isn’t acceptable to the Corps, then a full-blown environmental impact statement will be required, meaning months’ more delay. Finally, there’s a 30-day public comment period before the decision is made to grant or deny the permit. Normally a permit is granted or denied by the Corps’ local office, but because of the scope of the potential effects, that decision must come from the Corps’ major general in Washington, D.C. – and a federal historic preservation council also gets a chance to comment. It is the first time in the local office’s history that a decision on a project here has been bucked up to Washington, Murphey said.

Although the Corps itself, faced with TCC’s inaction, finally initiated the required reviews, Murphey said the district still needs to formally apply for the permit before it can do any construction on the levee or in the floodplain. Documents obtained by the Weekly make it clear that district officials have known since at least 2005 that it was required to do so. On Jan. 24, Wells said the district will file the application in about 45 days – more than a year after construction actually began.

What the college administrators, as well as its architect and construction managers, didn’t understand, according to the e-mails, was the law. In one e-mail, project manager Greg Ritenour asked the Corps for clarification on the law: “Are we required to provide an Environmental Assessment or is it a suggestion?” (emphasis by Ritenour.) He was told that it is the law and “compliance is required.”

The Corps was also asked if the environmental assessment already done for the Trinity River Vision project could be used by the college. The answer was a firm “no.” In permit terms, the two projects have no connection, Murphey said – though TCC’s architectural firms, BingThom of Vancouver, B.C., and Gideon Toal of Fort Worth, both have been intimately involved in the controversial TRV project, which if built will profoundly reshape the region just north of downtown. The idea that construction is happening without a permit – and hasn’t been stopped by the Corps – has Wright incensed. “Why is construction going on at that site?” Wright asked, repeating comments he made in a letter to the Corps. Wright, who lives in Fort Worth, is now a recruiting officer with the U.S. Naval Reserve, but his background is chock-full of preservationist bona fides. He has a master’s degree in historic preservation and worked for more than a decade as an architectural historian for the Georgia Department of Transportation and also for two years with the Corps.

And he is deeply committed to Fort Worth’s history. “It was on the south side of the … river, on the bluffs, where construction is currently under way, that the town of Fort Worth was founded,” he said. In his opinion that makes the site potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic places, just like the courthouse. Wright says it is simply wrong to build there.

Wright and Murphey worked together when Wright was with the Corps; Murphey is also his brother-in-law. But that doesn’t mean they are always on the same page about preservation law. Wright said that construction has now gone so far that any meaningful considerations of comments made by the public or preservationists is impossible. “The whole process has been hijacked,” he said. “It is foolish to begin a project if you have not acquired all the necessary permits. … The permitting process begins before construction. …What if they can’t get the permit? The taxpayer is stuck with the bill. These folks are poor stewards of the public’s money. “It is stunning to think what TCC could have accomplished by now if they had simply coordinated the planning process with state and federal regulatory agencies,” he said.

Murphey and Wells both said that Wright is wrong, and that the two halves of the project can be considered separately. The south side can be completed as a stand-alone campus,” Wells said. And it might become that, he added, if the college is forced to scale back its grandiose plans because the project is getting so costly. That would mean that classroom buildings for the teaching, health, business, and information technology professions would have to be incorporated into buildings on the south side – or scrapped, as the library has already been. Wells made no apologies for TCC’s failure to seek a permit before construction began. “There are two ways to do a project permit like this: Do all the engineering and design work and then ask for corps approval, or do it on a step-by-step basis,” he said. “We made a deliberate decision to seek the permit on the step-by step basis. That is, rather than applying for the permit and then working on the design, we began working on the design [for the north portion] … coordinating with the Corps” at each step with a goal of getting all the pieces accepted before consolidating them all into a final application. “This allowed us to begin construction on that part of the project not subject to Corps approval,” he said.

The approach was intended to save “money and time,” he said. The reality was just the opposite. Murphey said that Wright is correct in one important aspect: The whole project must be examined for historical impacts under the National Historic Preservation Act. But the effect on the floodway is confined to the north half, meaning that the downtown part of the project “requires no federal permit. … Therefore, there is currently no potential violation of federal law.” Murphey wasn’t as confident of that evaluation on July 2, 2007, when he outlined his concerns about the construction to Ritenour, repeating almost verbatim Wright’s take on the cart-before-the-horse permitting process: “Technically, actual construction cannot begin until [the review under NHPA] has been completed. An argument can be made that the undertaking, in the large sense, has already commenced and has foreclosed the opportunity of the THC and the Advisory Council to comment on … its effects.”

The Corps’ historical review for the campus on the levee, released late last year, does not bode well for the college. With the THC concurring, Murphey found a number of significantly historic properties that would be adversely affected by the construction of the north campus – the levee, the Tarrant County Courthouse, the Paddock Street Viaduct (that is, the Main Street bridge), and the old TXU plant west of the bridge, all buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. The adverse effects, he wrote, “are primarily to the visual setting, the location, feelings, and associations of the courthouse and the viaduct.” In other words, the public’s view of these familiar structures will be altered or even blocked. “The bluff and the levee have actual integrity loss … the loss of character-defining elements by removing trees, rocks, and earth,” he wrote. His conclusions went to the heart of the city’s main draw for tourists: “Loss of the bluff’s integrity would diminish the cultural identify of Fort Worth as ‘Cowtown’ and its Western history and heritage that forms the core of the city’s cultural identity. … The reasonable conclusion to be drawn when altering the historic epicenter of a city is that the alteration will initially diminish the setting.”

The Corps’ historical review for the campus on the levee, released late last year, does not bode well for the college. With the THC concurring, Murphey found a number of significantly historic properties that would be adversely affected by the construction of the north campus – the levee, the Tarrant County Courthouse, the Paddock Street Viaduct (that is, the Main Street bridge), and the old TXU plant west of the bridge, all buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. The adverse effects, he wrote, “are primarily to the visual setting, the location, feelings, and associations of the courthouse and the viaduct.” In other words, the public’s view of these familiar structures will be altered or even blocked. “The bluff and the levee have actual integrity loss … the loss of character-defining elements by removing trees, rocks, and earth,” he wrote. His conclusions went to the heart of the city’s main draw for tourists: “Loss of the bluff’s integrity would diminish the cultural identify of Fort Worth as ‘Cowtown’ and its Western history and heritage that forms the core of the city’s cultural identity. … The reasonable conclusion to be drawn when altering the historic epicenter of a city is that the alteration will initially diminish the setting.”

Even though TCC has yet to ask for a permit, the Corps is working on the next step in the process, a memorandum of agreement on what TCC must do to mitigate the damage its construction has done and will do. Murphey said development of that agreement must include all stakeholders – county preservationist groups, the public, the THC, the city, and the county – and TCC . And, he said, the legal memorandum must be finalized before the Corps will send the application to Washington for Corps officials to rule on. TCC must sign it and agree to implement the conditions or there will be no permit, he said.

Mitigation measures that are being discussed include reducing the height of the buildings, planting large numbers of trees to replace those destroyed in the gouged-out section of the bluff, establishing a credit course on historic preservation, and setting up a scholarship fund for needy students. “There will be additional costs, of course, associated with any mitigation that TCC is required to do,” Murphey said. In September, TCC completed a draft of its own assessment of environmental impacts of the north-bank construction. The Corps must evaluate it and determine if more work is needed. Not surprisingly, TCC found no adverse environmental effects of the structures on the levee and the floodplain.

Lawerence Oaks, executive director of the Texas Historical Commission, has been in the preservation business for most of his adult life. It is his unequivocal opinion that the project should have been required to get a permit before any damage to the bluff or other historical sites occurred. His letters and e-mails to that effect, sent to the chancellor since 2005, were met with silence, he said. Oaks has been at the state agency for 15 years and is respected as a fair, highly knowledgeable preservationist by local historical groups who have worked with him. That is why many here are puzzled over the district’s apparent snub of his goodwill offer three years ago.

In July 2005, Oaks wrote and phoned de la Garza asking for detailed information about the project and offering his help. “I never got a response,” he said, though there’s no question that the offer reached de la Garza – copies of Oaks’ letters were produced by TCC in response to the Weekly’s request. Oaks stumbled on the campus project by accident. The historical commission had been consulting on the Trinity River Vision project, the massive redevelopment scheme along the Trinity in downtown Fort Worth that has triggered extensive environmental and historical investigations, when he was told about the new campus. Like Murphey, Oaks took the initiative and contacted the college, to no avail. “I have written three or four letters and made phone calls over the past three years expressing our concerns [about the project] and offering our expertise on the law, but the chancellor never responded,” Oaks said. In the letters, he told de la Garza that the undertaking would require a permit from the Corps and the state historical office. “After all, we do about 12,000 of these [permitting processes] a year.” It was his “strong opinion” that the project should not go forward without the approved permits, he said.

Oaks is also puzzled about the college’s response when one of his staffers got through to an assistant to the chancellor and asked for detailed plans of the campus. The staffer was told they would be sent right away. When the promised documents didn’t show up, the THC staffer called back and was told that the chancellor “consciously made a decision” not to send the documents, with no further explanation. “We were not trying to stop the project, we were just trying to suggest that the [permitting process] should be done from the beginning,” the historic preservation officials said. Frustrated at the lack of response, Oaks and his staff called a meeting here two years ago, he said, inviting the college and the public, in order to explain “Here’s what our role is, and here’s what the law says.” About 50 people from the county historical societies attended, he said, but no one from the college. “They sent Gideon Toal.”

Historic Fort Worth Inc. is one of the groups here taken aback at the college’s failure to heed Oaks’ advice. “It would have been a better use of public funds if TCCD and its consultants had performed their due diligence and gone through the appropriate processes prior to starting construction,” HFW board chairwoman Lisa Lowry told the Weekly in an e-mail. “It is faster, cheaper, and more transparent when the required processes are scheduled into the project at the beginning. Delays serve only to frustrate … what are already complex situations,” she wrote. “One would hope the whole process would be open and transparent,” Oaks said. “That is what we aim for, but sometimes it doesn’t happen.” Wells said in an e-mail response to the Weekly that he was “not aware of any letters sent to TCCD” from the state historical commission except the one in July. “I was unable to find a copy of a letter from Dr. de la Garza responding to Mr. Oaks, but that does not mean that one was not sent,” he said. Wells also said he knew of no phone calls from Oaks. “That is not to say they didn’t happen, it’s just that no one … has a record [of them]. … To my knowledge, [the chancellor] responded to all communications sent to him from local historical interest groups.”

Wells said that he and de la Garza “never heard anything about” Oaks’ suggestion that they start the permitting process early. He also said that when Ritenour heard of the commission’s request for plans, he “promptly offered [by e-mail] to provide the plans needed. … A response was not received.” The district’s gestures toward complying with historic preservation laws haven’t ended up protecting much. The bluff, for instance, is subject to the state’s antiquities code, which requires any state entity to notify the THC and get a permit for an archeological survey before breaking ground on public land, Lowry said. TCC had to do a survey of all the sites it had purchased, for their historical significance, if any, to the city. The code, which is implemented by the state commission, requires that sites significant to the city’s, state’s, or nation’s history be identified for preservation either by saving the structure or by creating a fully documented record of what is found before demolition can occur.

TCC dutifully hired Dallas archeologist Dr. Alan Skinner to do the historical survey. But college officials then ignored his findings and recommendations, and OK’d the demolition of at least two structures and some parking lots in the targeted area that Skinner had specifically said needed to be left standing for further study and photographic work. Skinner was stunned, he said, “when I drove back to Fort Worth one morning and the buildings were gone.” Wells said the demolition happened because of “a miscommunication on someone’s part.” He said he didn’t know that Skinner had notified the college that the buildings should be preserved. But he also said that he assumed that Skinner would “make that happen” – presumably referring to an order to preserve the buildings. ” I’m still trying to figure out how this happened.” Wells said. “I have apologized for it.”

Despite that rather major violation of the antiquities code requirements, Skinner recommended to the historical commission that the project be approved. In response, he got a chastising letter from Oaks, who rejected the report and told Skinner that he needed to “clearly state that Tarrant County College destroyed the historic buildings recommended for further study.” Skinner’s reports were rejected three times, with all three letters from Oaks recommending that construction not proceed on the project. In the last, Oaks wrote, “Please inform your client that a full [Corps] review will be required, including assessment of all direct and indirect adverse effects.” In e-mails to Skinner – which the college has – THC deputy Bill Miller reminded Skinner that he had recommended to the college more than once that construction be stopped.

Oaks said he was also concerned about the destruction of a section of the historical bluff. “In essence, a huge building is being inserted into the bluff,” he said. And as for the bulldozed buildings, he said no one will ever know what was lost. “Fort Worth is a great city,” he said. “Its downtown is very livable. We want to keep it that way.” “What were the trustees thinking?” Larry Meeker’s normally courtly voice rose in intensity the more he lamented the Tarrant County College District’s decision to build the downtown campus. The Fort Worth native and oil company owner is outraged at what he calls a massive waste of education money and a betrayal of the people’s trust. Meeker’s criticism carries some weight. In 1965, he chaired the steering committee of local citizens who set out to establish a community college district that would serve the entire county. Success did not come easy. Strange as it may seem now, with TCC an integral part of community life, the small group of visionaries had to fight off opponents as disparate as the leader of the progressive wing of the local Democratic Party (who thought a junior college would be nothing more than a glorified vocational school) and powerful corporate types (who didn’t want their taxes raised).

His role was to sell the idea of a community college to the citizens and get the signatures needed to call an election – and he did. He crisscrossed the county that year, speaking and handing out petitions at every forum he could find. “It was the most exhausting thing I ever did,” he recalled over coffee at a bakery across from the TCC South Campus, the district’s first, completed in 1968. The group needed 3,000 signatures to get the proposed district on the ballot; he got 20,000. “And the rest, as they say, is history,” he said, and laughed. But the laughter didn’t last. “I have a huge emotional investment in this district,” he said. “We made a pledge 40 years ago to the people that we would provide a place where the most vulnerable, the most needy, the kids who had to drop out of school to go to work, single moms who want a better paying job, laid-off workers who need retraining, can get an education or learn a trade that would give them a chance to make their lives better.” What TCC doesn’t need, he said, is “a grandiose place where the trustees can see their names on a plaque. We need that money to go into education, provide scholarships, hire more teachers.”

Now Meeker is on another campaign. Once again he is speaking to every group he can find, even taking out half-page ads in local newspapers, expressing opposition to the downtown campus. “When the people I talk to understand what is happening, they are outraged,” he said. And yet, Meeker strongly supports the idea of building a downtown TCC campus – just one that’s much different, and far cheaper, than what’s on the boards now. Until this project, he said, trustees were prudent when building campuses. None of the four built to date have cost more than $150 million, some cost much less, and three are on land that was donated to the district. The idea of a downtown campus has been around from day one, he said, but there were other potential locations that were less disruptive, in no need of a permit from the Corps, and where a school “could have been built for around the same price as the others,” he said.

While Meeker’s concern goes to the heart of the educational mission of the district he helped create, his voice is just one of a growing chorus of critics just as disparate in their own ways as those in the beginning. Besides the local and state historic preservation officials, powerful downtown interests have vigorously opposed parts of the plan. Members of Downtown Fort Worth Inc., Sundance Square developer Ed Bass, and former councilwoman Wendy Davis (now running for the state legislature), have all objected to the plan for a sunken plaza leading to a pedestrian tunnel under Belknap Street that would connect the college to downtown. They have labeled the design as unworkable and the tunnel an open invitation to crime, raising fears about the safety of students. Steve Murrin, former city councilman and unelected “mayor” of the Stockyards, backed up Meeker’s concerns, telling the board last year to scale back the expensive project and put that money into education.

“We had not envisioned such an ambitious plan” when the downtown campus was first proposed, said Fernando Costa, head of the city’s office of planning and development. Once the city became aware of the scope of the plan, he said, “We asked the college to consider other sites” and suggested several, including the old downtown post office and other sites along Lancaster Avenue. Some thought the area near the Intermodal Transportation Center, on Jones Street, would have had the major advantage of providing easy transportation access for students. The college rejected all of the ideas, Costa said. In lengthy interviews, Wells told the Weekly the long-discussed but still-vague idea of a downtown campus came into sharp focus in 2000 after the administration took a hard look at local population growth and the rapid residential development in downtown Fort Worth. “The downtown campus’ time had come,” he said. The board passed a three-cent hike in the tax rate for its maintenance and operations budget a few years ago in order to generate funds for the campus that de la Garza has said would be a “pay-as-you-go” project with no borrowing.

However, as the campus costs spiraled out of control, the college has not only had to spend half its contingency fund, but it tried to find more money from one of the downtown tax increment financing districts. In a July 2007 TCC board meeting, Randy Gideon of Gideon Toal Architects and the president of the board of Downtown Fort Worth Inc., told the trustees that though there was talk of up to $4 million in TIF funds becoming available, the idea was quashed. “No direct benefit, or indirect benefit, [from a TIF] is going into the TCC project,” said Jay Chapa, Fort Worth director of economic development, because TCC is a tax-exempt entity that pays nothing into the TIF. The idea of building the campus on the river came from eliminating other sites as not suitable, said Wells, including those suggested by the city. “We needed room for at least 400,000 square feet of classroom and office space, with room to expand to 800,000 square feet by 2023,” he said.

At the time, there was widespread support for the idea. De la Garza had envisioned the campus spanning the river, and BingThom Architects gave him the plan that would make it happen. The district began to buy up properties along the bluff.

The single largest tract was the old TXU power plant just west of the bridge, with its smokestacks that had been landmarks here since 1910. The district also bought TXU’s property east of the viaduct, paying $27 million for both tracts. Wells said the college hopes to restore the plant and its machinery for possible use as a museum. Howls of protest from history buffs – the first of many on this project, as it turned out – ensued when the district announced it was going to take down the stacks “for safety reasons.” Wells said the district wanted to save them but TXU would not sell unless the district committed to indemnifying the company permanently against any accidents involving the stacks. “We couldn’t afford to do that,” he said. A large tract was bought from Ed Bass for close to $5 million. Attorney Joe Johnson’s old building on the corner of Belknap and Main streets, only about a tenth of an acre, went for $1.3 million.

And as the district tried to find a culprit in this fiasco, it hit upon the Corps as the bad guy. In 2006, Wells said college officials began to perceive a change in the way the Corps approached the review of the project. “We believe the change was the result of a much more focused effort at applying rules … resulting from the long- term impacts of … Hurricane Katrina. … Our team believes very strongly that if Katrina had not hit New Orleans, we would be well on our way to completion of the project.” But for Wright and others, there is no doubt who is responsible and it’s not Katrina. “Keeping their plans secret, stonewalling legitimate inquiries by other government agencies, and failing to apply for a permit in a timely fashion has damned their mighty project,” he said. “Is it arrogance or ignorance or a little of both? Whatever, it’s a scary thought that this is an ‘institute of higher learning.'”

You can reach Betty Brink at

bettybrink@att.net.