Memento scavengers made hit-and-run stops for two days, stepping out of their cars to survey the pile of rubble in hopes of nabbing a brick, a fixture, a cinder block painted a familiar blue, any reminder of Fort Worth’s most recent rock ‘n’ roll casualty.

The demolition guy understood people’s pain.

“You can grab something along the outer edge, but don’t get out in the middle of the pile and mess around,” he said, perched atop a backhoe. Scattered around him were the sad, dusty remains of the Wreck Room. Opened in 1997, closed last September, and hammered into ruins this month, the Wreck was the city’s coolest club, and its flattening leaves a void far bigger than the now-empty lot at 3208 W. 7th St. In the Wreck’s heyday, downtown workers stopped by for after-work drinks and a cheap thrill in the hip but slightly ominous environs. By 10 p.m., drifters, rockers, punks, bikers, scenesters, stoners, boozers, and assorted flunkies and junkies had flocked to the joint where various misbehaviors were tolerated if not openly encouraged. Providing a soundtrack to the shenanigans were edgy bands such as Doosu, the Gideons, and The Flametrick Subs, the last of which boasted a fingerless bass player, a tiny drummer, and “Satan’s Cheerleaders” – young women in pleather outfits with “666” sewn on front.

“You can grab something along the outer edge, but don’t get out in the middle of the pile and mess around,” he said, perched atop a backhoe. Scattered around him were the sad, dusty remains of the Wreck Room. Opened in 1997, closed last September, and hammered into ruins this month, the Wreck was the city’s coolest club, and its flattening leaves a void far bigger than the now-empty lot at 3208 W. 7th St. In the Wreck’s heyday, downtown workers stopped by for after-work drinks and a cheap thrill in the hip but slightly ominous environs. By 10 p.m., drifters, rockers, punks, bikers, scenesters, stoners, boozers, and assorted flunkies and junkies had flocked to the joint where various misbehaviors were tolerated if not openly encouraged. Providing a soundtrack to the shenanigans were edgy bands such as Doosu, the Gideons, and The Flametrick Subs, the last of which boasted a fingerless bass player, a tiny drummer, and “Satan’s Cheerleaders” – young women in pleather outfits with “666” sewn on front.

The Wreck was loud, cheap, and squalid, its patrons wild, weird, and, for the most part, friendly. “The Wreck Room was a lovable dungeon,” bartender Cary Blackwell said. On nights when 2 a.m. arrived too soon, the bar’s doors were locked, and the diehards carried on, keeping an eye out for police, DEA, TABC, or any other buzz killers with badges.

Ahhh, the good ol’ days … screwing in the bathroom. Snorting coke off flesh. Puking in the corner. Dogs roaming. Music blaring. Laughter. Smoke. Yelling. Tattoos. Graffiti. Fights, with band members diving into the fray. Now those sights and sounds, the marks of a good rock club, are gone like the last bong hit at a Me-Thinks gig.

Former Wreck owner Brian Forella nailed it: “Everything has gotten more mainstream,” he said. “Most people don’t want to go to a place where people are peeing in the sink.”

It sucks to see the old gal go, but the Wreck’s demise is just another in a long line of Cowtown clubs that came, conquered, and collapsed, but live on in boozy memory. Mourners scattered across the city recall glorious nights spent lounging on floor cushions at The Cellar in the 1960s, chugging a Wild Ass Indian (the house drink with five shots of 151-proof rum) at Spencer’s Corner in the 1970s, dancing to the spandex-sporting rockers who made Savvy’s Nightclub legendary in the 1980s, or moshing in Pantera’s pit at Joe’s Garage in the 1990s.

Letting go hurts, especially when a club has become part of your personal lore, a scuzzy home away from home, a place where both innocence and brain cells die every night, casualties of the all-important quest for a damn good time.

Letting go hurts, especially when a club has become part of your personal lore, a scuzzy home away from home, a place where both innocence and brain cells die every night, casualties of the all-important quest for a damn good time.

Ground zero of Fort Worth’s rock club past is 1959. The Cellar – the original, not the current one on West Berry Street – opened in a downtown basement at 1111 Houston St. and moved a few blocks north after the original building burned. What began as a beatnik coffeehouse evolved into a rock club in 1964 with killer house bands playing from dark until dawn.

Because the bar didn’t have a beer or liquor license, it could stay open all night. In those pre-1971 days before Texas legalized sales of liquor by the drink, The Cellar sold set-ups to customers who carried in packaged liquor. The club also sold cocktails with bourbon or vodka “flavoring” – fake booze. Only VIP customers got the real thing.

“It was all fake liquor unless you knew somebody,” said Mace Maben, guitarist and singer for Courtship, one of the house bands from 1969 to 1971. “If you were in the band you could order a ‘special,’ and that was Everclear with green food coloring, so if the cops came in they would think it was a lemon-lime soda.”

Owner Pat Kirkwood despised drugs and banned their use on his property, but that didn’t thwart the party. “Anybody who came to town always ended up at The Cellar,” recalled Roy Stamps, a regular customer and former 1360-AM/KXOL radio newsman. “It was dark, with black lights and ’60s flower-child stuff painted on the walls.”

“And on the people,” his wife, Sylvia, chimed in.

Unlike licensed bars, which had to close at midnight, The Cellar was hopping until 6 in the morning. Scantily clad waitresses carried pen flashlights so they wouldn’t step on the customers reclining on floor cushions, and they were expected to shimmy on command. “Jimmy Hill, the manager, would yell, ‘Meat on the table!’ and the girls would get up and strip,” Maben said. “There was a runway right in front of the band. It was pretty much Sodom and Gomorrah.”

Hill was 20 when he started managing the club in 1962. Now 65, he remembers the old days in vivid detail, including the celebrities who stopped by – George Carlin, Rowan and Martin, Clint Eastwood, and hell-raising actor Lee Marvin, who hit town to promote his 1962 film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Despite numerous news media interviews and promotional stops scheduled for the following day, Marvin arrived at The Cellar ready to party. “He got drunk and picked up one of our waitresses, and the next day he didn’t make any of his interviews,” Hill said. “Nobody heard from him for three days.”

Hill still has a vest Marvin handed him that night. “I told him I liked his vest, and he took it off and gave it to me,” he said. “I wish I could still wear it.”

By the early 1970s, suburban flight was killing downtown, and the club was outdated and hindered by Kirkwood’s racist door policies. “They had a sign at the top of the stairs that said, ‘The Cellar has the highest cover charge in the world – $1,000,'” Maben said. “When a black person tried to come in, they’d say, ‘Can’t you read the sign?'”

By the early 1970s, suburban flight was killing downtown, and the club was outdated and hindered by Kirkwood’s racist door policies. “They had a sign at the top of the stairs that said, ‘The Cellar has the highest cover charge in the world – $1,000,'” Maben said. “When a black person tried to come in, they’d say, ‘Can’t you read the sign?'”

Teens, however, had no problems getting in, although the club’s notoriety scared away most. They were more likely to hit one of the city’s under-21 clubs, such as The Circus Club, The Box, or Holiday A Go-Go. This was before DJs and compact sound equipment – rock bands were in demand, and teen clubs were hopping with mostly good clean fun. “We went to hear the bands, check out the chicks,” said Frank Cagigal, who was inspired to become a lifelong musician (he currently plays keyboards with Little Joe and La Familia).

“You got your Dr Pepper and listened to the band and stayed as late as your parents would let you,” recalled Juke Jumpers bassist Jim Milan.

The glory days of nasty rock clubs were ignited in the mid-1970s, after relaxed liquor laws made bars more profitable and numerous, and the minimum legal drinking age fell from 21 to 19 and then to 18, which meant 16- and 17-year-olds could usually sneak in with fake IDs. Suddenly, youthful exuberance laced with legal booze and plenty of venues created a booming rock scene. Throw in the suburban proliferation of marijuana, and Sodom and Gomorrah dialed up another notch.

The Speakeasy and I Gotcha were hotspots on the West Side. Daddio’s kicked ass downtown. There was Omar’s on the North Side and The Hungry I out east. But the two most popular places were near TCU – The HOP on West Berry Street (current home of The Aardvark), and Spencer’s Corner on University Drive.

The HOP (an acronym for House of Pizza) was small, which added to its charm. Jim Colegrove arrived in Fort Worth in 1974 from Woodstock and formed a band with Stephen Bruton called Little Whisper and the Rumors. They played one of their earliest gigs at the little pizza joint. “The room was probably half as big as it is now,” Colegrove said. “It would hold 100 people when it was full. It was extremely eclectic, and I heard all kinds of bands in there.”

The HOP (an acronym for House of Pizza) was small, which added to its charm. Jim Colegrove arrived in Fort Worth in 1974 from Woodstock and formed a band with Stephen Bruton called Little Whisper and the Rumors. They played one of their earliest gigs at the little pizza joint. “The room was probably half as big as it is now,” Colegrove said. “It would hold 100 people when it was full. It was extremely eclectic, and I heard all kinds of bands in there.”

The vibe attracted the voice of a generation. “Bob Dylan came into the club one night when Little Whisper and the Rumors were playing,” he said. “Not long after that, [club management] hung a big portrait of him by the table where he’d been sitting.”

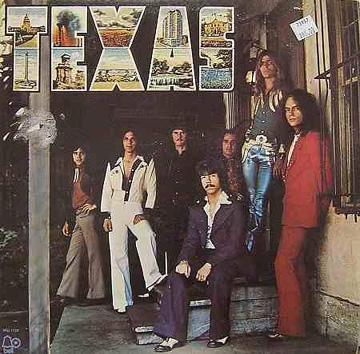

Nearby, Spencer’s Corner routinely ignored its 350-person occupancy limit and was usually packed with 500 thirsty kids and a long line of others standing at the door, itching to get inside. One of the top bands was Texas, featuring former Courtship frontman Maben. “That was back in the good old days,” he said. “The drinking age was 18. It was wild – the true era of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. I remember being carried off the stage a couple of times.”

Sammy Roberts started working as a bartender in 1975 and eventually became manager of Spencer’s Corner and its larger sister, Spencer’s Palace (farther north on University Drive). “I don’t know how I lived through it,” he said. “I was a glorified babysitter for 500 people. There was always a fight. But when it was the Corner, it was the premier place to go, with all the best bands playing there.”

Guys gladly paid a $3 cover for the wet t-shirt contests and Naughty Nightie nights. Spencer’s courted women customers with free drinks from 8 to 9:30 p.m. and no cover charge. A photographer took candid snapshots of the revelers and created a weekly slide show projected on the wall behind the stage “so everybody could see how drunk they were the weekend before,” Roberts said.

Owner Jim Spencer, however, was soon sidetracked by another development – Billy Bob’s Texas, billed as the largest honkytonk in the world. He neglected his rock clubs, and they were beginning to fizzle by 1980, but by then a new venue had stolen the spotlight.

Owner Jim Spencer, however, was soon sidetracked by another development – Billy Bob’s Texas, billed as the largest honkytonk in the world. He neglected his rock clubs, and they were beginning to fizzle by 1980, but by then a new venue had stolen the spotlight.

The Arlington rock club Savvy’s Castle was outdrawing its 250-occupancy limit on Division Street in the mid-1970s and moved into a 5,500-square-foot space at a Fort Worth shopping center on East Lancaster Avenue in 1977. The renamed Savvy’s Nightclub held more than 500 patrons but outgrew its new quarters almost immediately. The club was home base for Savvy, a six-man band that dropped its disco origins and transformed itself into a rock group, complete with tight spandex pants and lots of hair. Frontman Ricky Lynn Gregg was a teenage wunderkind who could wail on guitar, sing like a sweet demon, and drive women wild with his shirtless costumes.

In 1979, the bar doubled its space by knocking out an adjoining wall. Yet even with 1,000 people crammed inside, a line sometimes stretched outside the building. People danced under a ceiling of red and white tiles (later painted black) and drank formidable amounts of booze. “The Budweiser distributor said we were second only to Rangers Stadium in beer sales,” said Savvy drummer Rick Miller, whose family owned the club.

Wednesdays were quarter beer nights, and a bar-back called Rat Man said the golden flow never slowed. “From 7 p.m. until close, I turned on the keg tap one time,” he said. “I filled pitcher after pitcher all night long and never turned off the tap.” Bartenders pulled in $200 in tips, not to mention the Black Mollies and Quaaludes that were tossed into the tip jars and divvied up at night’s end.

The house band’s loyal fans came out in droves six nights a week. And then the 1980 Texas Jam fiasco pushed them into orbit. A battle of the bands was held in Dallas, with the winning group slated to open the highly anticipated Texas Jam with The Eagles, Cheap Trick, Foreigner, Sammy Hagar, and others at the Cotton Bowl. Savvy won the competition, but on the day of the concert the Eagles’ management got Savvy cut from the bill for reasons that are still unclear. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported the snubbing, other news outlets picked up on the story, and Savvy was suddenly the state’s lovable underdog. The band’s reputation – and the bar’s attendance – skyrocketed. National acts such as the Gregg Allman Band, Steppenwolf, Humble Pie, and the Guess Who played there. Other rock stars came in just to drink and carouse, including Frank Zappa and Aerosmith’s Joe Perry, who got snippy while smoking a joint with Savvy members because it wasn’t getting passed back to him fast enough.

“Once the ’80s hit, Savvy’s and the Agora [in Dallas] were the premier rock places around,” guitarist Steve Jones said. “Savvy’s was blue-collar rock ‘n’ rollers who’d be out all night, every night.”

Gregg, fresh out of high school, suddenly found himself playing in front of a packed house. “It was like going to rock ‘n’ roll college,” he said recently from his home near Nashville. “There weren’t any rules, no laws, it didn’t matter what you did. Part of Savvy’s legacy was drinking with the crowd. There’d be at least 10 rounds of drinks a night, so I learned to drink, too.”

East Lancaster Avenue was on a downhill slide by then, and the police weren’t overly interested in what occurred there. The party went on unabated. Many nights, patrons would follow the band back home (the band members lived together in rent houses) and party until sunup. Savvy recorded Made in Texas, an album of originals, in 1982 at Pantego Sound Studios. Engineering was by Charles Abbott, father of Pantera’s Vinnie Paul and Darrell, and his boys hung around wide-eyed during recording sessions. Darrell, who hadn’t yet adopted the nickname “Dimebag,” was already a prodigy. “He was a phenomenal guitar player at 13,” Gregg said. “By the time he was 15, Pantera was playing Savvy’s on a regular basis.”

East Lancaster Avenue was on a downhill slide by then, and the police weren’t overly interested in what occurred there. The party went on unabated. Many nights, patrons would follow the band back home (the band members lived together in rent houses) and party until sunup. Savvy recorded Made in Texas, an album of originals, in 1982 at Pantego Sound Studios. Engineering was by Charles Abbott, father of Pantera’s Vinnie Paul and Darrell, and his boys hung around wide-eyed during recording sessions. Darrell, who hadn’t yet adopted the nickname “Dimebag,” was already a prodigy. “He was a phenomenal guitar player at 13,” Gregg said. “By the time he was 15, Pantera was playing Savvy’s on a regular basis.”

Back then, Pantera was glam, with platform shoes and pretty shirts, and Darrell went by the name “Diamond.” Later, the band become synonymous with heavy metal and with Joe’s Garage, a Westside club that looked just like its name sounded.

But the world was changing. Drunken kids were killing themselves on highways nationwide, creating pressure to raise the legal drinking age and leading to liability issues for clubs. Mothers Against Drunk Drivers was formed in 1980. The next year, the drinking age in Texas went from 18 to 21. To survive, clubs resorted to comically desperate measures. Savvy’s stretched a chain link fence across the middle of the bar to keep minors segregated; the poor kids looked like goats eyeing a new gate.

It was the end of an era. “Prior to that you could go out any night of the week and find action, but it just dried up almost immediately,” Savvy band manager Jerry Hudson said. “Savvy’s Nightclub, instead of being a big place full of people, was a big place with very few people.”

It was the end of an era. “Prior to that you could go out any night of the week and find action, but it just dried up almost immediately,” Savvy band manager Jerry Hudson said. “Savvy’s Nightclub, instead of being a big place full of people, was a big place with very few people.”

The death knell resounded across town. “It killed the scene,” Spencer’s Corner manager Roberts said. “The clubs lost three years of drinkers. Within 12 months, 75 percent of the venues were gone.”

Music was also changing. Punk and metal were hot, and bands such as Savvy, even though members were still in their 20s, were “dinosaurs marked for extinction,” Jones wrote recently in his fascinating online journal (www.stevejonesproductions.com). Gregg realized Savvy could no longer survive on Journey and REO Speedwagon covers but couldn’t envision a metal makeover. He split and formed a country-rock act. Savvy never recovered from his loss, and within a few years the band and the club were done.

But rock ‘n’ roll is like a cockroach – hard to kill. A club farther west on East Lancaster Avenue, near Beach Street, was creating an underground stir, kick-starting a new generation of venues geared toward putting kids and rock bands together by setting higher cover charges, sacrificing booze profits, and letting kids show up pre-medicated.

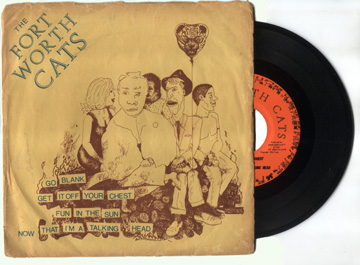

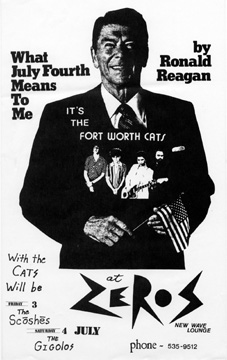

In the late 1970s, the music being pounded out by The Fort Worth Cats (the band, not the baseball team) enthralled Richard Fenner so much that he and a friend opened a bar in 1980 just to feature one of the city’s earliest punk outfits. Zeros New Wave Lounge became the city’s first punk club, not a big deal at the time. By then, the Cats were becoming so popular they soon outgrew the small club. But punk bands outnumbered venues back then, and it was easy to find musicians. “We started getting calls from all over the country, bands coming through,” Fenner said. “Texas and the whole country were alive with new-wave punk bands.”

National acts such as Black Flag, X, and Rank and File performed. The Delinquents arrived for a gig one night with influential rock critic Lester Bangs in tow. Avid punks wore the expected attire – dog collars, safety pins, and the like – but most of the crowd showed up in traditional Fort Worth garb of jeans, t-shirts, and boots. Police assumed the worst. “They raided our place all the time,” Fenner said. “They claimed there were a lot of parents calling the police saying to check it out.”

A benefit for the United Farm Workers Association, called Rock Against Reagan, even brought federal scrutiny. “We had some suspicious-looking men in black – Secret Service-looking guys – come in and check us out because Ronald Reagan had just gotten elected that year,” he said.

A benefit for the United Farm Workers Association, called Rock Against Reagan, even brought federal scrutiny. “We had some suspicious-looking men in black – Secret Service-looking guys – come in and check us out because Ronald Reagan had just gotten elected that year,” he said.

By 1982, Zeros was gone.

“I was getting burned out, and there were other clubs starting to book some of our bands,” Fenner said. “Spencer’s Corner was even booking a New Wave Wednesday.”

That was one of the last-gasp efforts by Spencer’s, Speakeasy, Savvy’s, and all the other 1970s hot spots. Clubs were shifting toward older crowds that preferred strong drinks and softer music. Large venues gave way to neighborhood bars. Kids were out of luck. And then along came Kelly Parker and Melissa Kirkendall.

“It seemed like a fun thing to do,” Parker said, explaining why he opened The Axis in 1989 at South Main Street and Magnolia Avenue. He was working as a cook at The HOP and playing in a band called The League of None, and he and others leased a building and went into the latest incarnation of the rock club business – no booze license, no oak bar, no employees, just a big place to gather and hear live music. “Like many young males we thought it would be cool to own a rock ‘n’ roll bar,” he said. “Everybody thinks about it. Some are nutty enough to do it.”

One of the first to beg for a gig was an unknown band called the Toadies. Nobody knew that, five years later, the band’s debut album would go platinum. Their early Axis shows were sparsely attended, but Parker loved them and let them open for the nationally acclaimed Goo Goo Dolls.

The Axis was undone by a run-in with an off-duty cop six months later. Customers were standing outside the club one night when the driver of a passing car – the cop – heaved a beer bottle at them. “These punk rock kids got mad, and they went chasing after him,” Parker said. A fight ensued, and the off-duty cop lost. And then Parker lost. “A day or two later, there were helicopters and fire marshals and police everywhere,” he said. “They shut the place down. I was over occupancy and had some minor building code violations, but the reason they shut us down was their buddy got beat up by some of my patrons.”

By then, the Toadies were developing a local following, and crowds were growing. Parker teamed up with Kirkendall to open Mad Hatter’s in the strip center next to King Tut on Magnolia Avenue. But a club that relies on cover charges instead of booze profits needs space – something the location lacked. “There wasn’t much room to park,” Parker said.

On at least one occasion, the Toadies paid the club’s light bill so the show could go on. “They needed electricity, and we needed electricity,” Toadies bass player Lisa Umbarger said. “I don’t know if the Toadies would have broken in the Metroplex if not for the Mad Hatter’s shows. It was a small place, and when we played there we would pack it, and it made it seem like the tickets were harder to get than they really were. Record people would come to those shows that were jam-packed with sweaty people. They could feel the energy, and they wanted to sign us.”

After three years, the operation moved to Vickery Boulevard. Rechristened the Engine Room, the building boasted 4,000 square feet and a balcony. “There were times we had 1,000 people. We were way over fire code, but there were crack houses right down the street, and the fire marshal wasn’t crazy enough to come down to that area,” Parker said.

After three years, the operation moved to Vickery Boulevard. Rechristened the Engine Room, the building boasted 4,000 square feet and a balcony. “There were times we had 1,000 people. We were way over fire code, but there were crack houses right down the street, and the fire marshal wasn’t crazy enough to come down to that area,” Parker said.

Then the May 5, 1995, hailstorm hit. Newspapers reported the horror it caused at Mayfest but didn’t mention its impact on the city’s gnarliest bar. “It absolutely destroyed the roof,” Parker said. “The next day you could look right through the roof and see blue sky.” A rainy summer meant frequent water damage, and the landlord allegedly wasn’t keen on sinking money into the property. It was time for another move, this one a short hop down the street to the old Stage West building. The Impala debuted in 1997 with a full liquor license but closed its doors the next year.

“I was getting burned out on the whole bar thing,” Parker said. “There’s only so many times you can shop-vac puke off your furniture before you get tired of it.”

But what a ride. Nirvana (pre-Nevermind) played at the Axis for about 30 patrons, and Korn played the Engine Room to fewer than 100. The 1990s had been a sensational era for local rock music, and just when the hangover was setting in, the Wreck fired up the party all over again and dragged it into the new millennium, for another short but wild rock ‘n’ roll ride.

Today the city’s ranks of darkly delicious rock clubs have thinned. More mainstream rock bars such as The Aardvark and The Moon carry on, along with the punk venue 1919 Hemphill and the Ridglea Theater. After the Wreck’s demise, Forella started a new endeavor, Lola’s (formerly 6th Street Live). But he’s mellowed and wants a more conventional club these days. His crowd is tiptoeing into maturity, leaving a space for the next underground scene.

“There is no holy grail left in the Metroplex,” Umbarger said. “It’s all been commercialized and bought up. Something new has to start. I talk to so many kids who were young, 13 years old, who would go to the Axis or Mad Hatter’s, and then they’d start a band and go out and play.

“But you have to have clubs for that to happen,” she said, and, for now, in this town, “there’s no place for them to go.”