When Patsy Keifer got busted for DWI while sitting at the side of a country road in her broken-down Chevy pickup, it didn’t surprise her.

She’d refused to take a sobriety test, after all, and told the officer she’d been drinking beer earlier in the day. But winding up strapped naked to a restraining chair throughout a night at the Johnson County jail wasn’t something she’d bargained for. Nor could retiree Norman B. have anticipated that the presence of two tires far away from the flames in a fire pit on his rural property would result in a weekend in jail and getting knocked down and kicked by a jail guard. But that’s the kind of thing that seems to happen with some frequency in the county jail located on the outskirts of Cleburne. Welcome to Johnson County, where rural beauty masks a dangerously out-of-whack criminal justice system, including abusive jailers and overzealous patrol officers, backed by prosecutors willing to let people sit in jail for months without trial — and voters who seem willing to overlook all of that, as long as the system is “tough on crime.”

She’d refused to take a sobriety test, after all, and told the officer she’d been drinking beer earlier in the day. But winding up strapped naked to a restraining chair throughout a night at the Johnson County jail wasn’t something she’d bargained for. Nor could retiree Norman B. have anticipated that the presence of two tires far away from the flames in a fire pit on his rural property would result in a weekend in jail and getting knocked down and kicked by a jail guard. But that’s the kind of thing that seems to happen with some frequency in the county jail located on the outskirts of Cleburne. Welcome to Johnson County, where rural beauty masks a dangerously out-of-whack criminal justice system, including abusive jailers and overzealous patrol officers, backed by prosecutors willing to let people sit in jail for months without trial — and voters who seem willing to overlook all of that, as long as the system is “tough on crime.”

The county just south of Fort Worth has more than 100 churches and until a year ago was nearly dry. Folks still have to drive 10 miles into Tarrant County to buy a shot or a bottle of whiskey. Illegal drugs, even in personal quantities, aren’t just frowned on — they’re the stuff of local newspaper headlines. Arrest statistics suggest that one in 13 adults in the county wind up in the criminal justice system — more than double the rate of Tarrant County, for instance — and the arrest rate is still rising. Johnson suffers, on average, only one or two murders and maybe 50 robberies a year. And yet, in just two months, inmates reported to Fort Worth Weekly — with many of their stories back up by officials — at least half a dozen instances of abuse and serious neglect by jailers, in some cases life-threatening, and out-of-line conduct by various patrol officers.

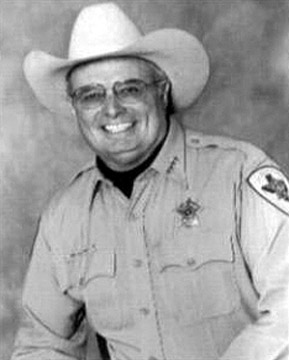

Johnson County Sheriff Bob Alford, who has ultimate responsibility over the jail, doesn’t deny most of the incidents alleged to have taken place there. He has taken action against some guards and expressed outrage over other examples of abuse, which he is investigating. But he also said that his hands are tied, in part, by budget restrictions that ensure the jail will be understaffed and employee turnover high. And, he said, he has no control over healthcare — or the lack of it — for inmates. On Oct. 25, 2005, Cleburne homemaker Patsy Keifer, then 46, was mixing housework with a few beers when the phone rang. It was her sister-in-law, who lived in a nursing home on Sycamore School Road. She needed Keifer to run an errand for her. “So I hopped into my husband’s old Chevy, and the next thing I knew the front left wheel came off, and I pulled over into the ditch on the side of the road.”

A Cleburne patrolman pulled up a few minutes later to see if he could help but smelled beer on her breath and asked if she’d been drinking. She told him about the beer and housework routine. He asked her to do a roadside sobriety test. She refused. He arrested her for driving while intoxicated and brought her to the Johnson County jail for booking. After mugshots and fingerprints, Keifer — who had a previous DWI in 2000 — was put into a holding tank. A little while later voices were raised, and a female guard, Sgt. Simpson (Kiefer didn’t know her first name and the Johnson County Sheriff’s Department wouldn’t release it), entered the holding tank, blamed Keifer for the raised voices, and removed her to another cell, one with no toilet. When Keifer needed to go to the bathroom, she used the intercom and asked to be taken to a toilet. When there was no response, she asked again. And again.

In fairly short order, Simpson and two other female guards showed up to take Kiefer, not to the bathroom, but to yet another cell. In its center sat an oversized chair equipped with restraining straps on the legs and handcuffs on the arms, facing a windowed door. Keifer said that she asked the guards what was going on and that Simpson answered: “I’m going to show you who the boss is.” Keifer was then ordered to strip and get into the chair. She refused and demanded her one phone call. Simpson refused her the call, then began taking off Keifer’s clothes for her, until the prisoner was completely naked.

At the guards’ command, Kiefer sat in the chair. The guards put a wide leather strap around her midsection that bound her to the back of the chair, then handcuffed her arms and strapped her legs in place. As the chair was oversized, Keifer’s thighs were spread open.

By the time the guards left, Keifer could no longer control her bladder and urinated on herself. To make matters worse, within a couple of hours she began to menstruate, leaving her in a puddle of blood and urine. Her humiliation was compounded when she saw guards — male and female — repeatedly looking at her through the cell door’s small window. Keifer said that she begged several times to be allowed to use the restroom, to no avail. Her ordeal lasted more than 10 hours, until a guard shift-change brought in a new guard whom Keifer described as “an angel.” Keifer was cleaned up and allowed to dress and make her phone call before she was returned to the general jail population. She said other inmates told her that Simpson was well known for her use of the chair and that “she also liked to use Mace and her Taser on inmates.”

By mid-morning, Kiefer’s husband — who’d had no idea of her whereabouts until she called him — had arranged bail, and she was released. Her husband took her to the Cleburne Family Medical Center, where medical workers documented deep bruising on her wrists and legs and noted that she was suffering from anxiety. She wound up receiving intensive therapy to deal with the psychological trauma of that night. Within a week of her release, Keifer and her husband filed a formal complaint with the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office. Two weeks later Lt. Troy Fuller from the Criminal Investigations Division wrote to her that he had found a “significant amount of information pertaining to this investigation” and had interviewed numerous guards, inmates, and others who might have seen “the interaction between yourself and Sgt. Simpson.”

Four months later Kiefer’s lawyer reported to her that Johnson County authorities could find no record of any investigation into the matter. However, Fuller told the Weekly that the attorney was mistaken, since Fuller still has a copy of that report.

Four months later Kiefer’s lawyer reported to her that Johnson County authorities could find no record of any investigation into the matter. However, Fuller told the Weekly that the attorney was mistaken, since Fuller still has a copy of that report.Keifer was livid. “No one should ever have to go through what I went through that night. This isn’t the dark ages.” She sued Johnson County for half a million dollars. Shortly thereafter, Simpson was fired. “The incident you’re asking about did indeed happen,” Sheriff Alford told the Weekly recently. “It was a one-time incident, and I looked into it personally. And the guard responsible was fired. We no longer even have that chair at the jail.” It was the first admission by a Johnson County official that Keifer’s story was accurate.

Alford, who’s been sheriff since 1997, is not part of the good ol’ boys network that runs much of Johnson County’s politics. He is considered a straight shooter who takes a personal interest in the treatment of inmates at the jail his office runs. Still, what happens there is ultimately his responsibility. “I fully accept the responsibility for the treatment of the inmates,” Alford said. “I explain to each one of my people — most of whom are pretty good — that most of those inmates are pretty good people too. They just made a bad choice or bad choices. But I expect them to be treated like people, not criminals.”

In the 10 years he’s been sheriff, “we’ve put nine of our guards in that jail for abusing inmates,” he said. “That should tell you how I feel about it.” But some people think Alford is being purposely kept in the dark about a lot of the problems at the facility. “He’s not always informed about what’s going on,” said Don Rice, publisher of the weekly Cleburne Eagle News. “I don’t know if that’s because his people want to protect him from the truth or they don’t want him to know it for their own reasons.”

Take the punishment chair, for example. Cpl. Pam Jetsal, the Sheriff’s Department media liaison, said it’s still there. “There’s one chair, way up in the front of the jail. My office is way in the back, so I can’t tell you how often they use it. But we still have it.” In some cases in Johnson County, abuse at the jail is preceded by the kind of arrest that wouldn’t even have happened in most communities. Norman B., a slight, 65-year-old retired Lockheed executive and diabetic who asked that his full name not be used in this story, was burning a mesquite tree in a large fire pit on his 10-acre property in Joshua last February when a crew from the Mid-North Volunteer Fire Department showed up and told him to put it out. “I asked them why I shouldn’t burn a mesquite tree and was told there was a burn ban. Well, I told them I’d passed the firehouse and checked and they had a sign up saying there was no burn ban that day. And one of them fellas told me that didn’t mean anything.”

While that discussion was going on, firefighters noticed two tires in the opposite end of the pit from where the fire was burning. “Neither was near the fire, but those boys sure got excited when they saw them,” he said. The retired executive said he lets neighbors bring old tires to his place and periodically has them hauled away. In this case he thinks a neighbor’s kids must have tossed them into the pit. Norman said he’d moved them out of the way of the fire he was starting. In fact, he said, one firefighter jumped into the pit and grabbed the tires with his bare hands to remove them — proof, Norman said, that they weren’t burning or close to burning. A Joshua police officer arrived, and Norman was arrested for violation of the Texas Clean Air Act — an extremely rare occurrence. According to Norman’s attorney, Christopher Cooke, individuals found to be in violation of that law are usually issued warnings or tickets; stricter enforcement actions are almost always against businesses for much more serious violations.

Norman was taken to the Johnson County jail. Several hours later he began to go into diabetic shock. “I knocked on the door to the guard’s room,” he said. “When there was no response, I banged on it. I needed my insulin.” The door opened, and a female guard, Cpl. Patricia Murphy, asked what he needed. While they were talking, a second guard, Cpl. James Blankenship, came roaring out of the room “and asked what the hell I thought I was doing, banging on the door like that. I told him I needed my insulin, and he told me I didn’t need any damned medicine, then he hit me, and I went backwards and fell. Then he started kicking me and said ‘This is my jail. I will run it as I damned well want to.'” Murphy backed up Norman’s story. “It happened exactly as you’ve been told, except he was really pushed hard instead of hit and walked backwards very quickly until he lost his balance and wound up landing very hard on a bench on the far wall of the room.”

Blankenship was unavailable for comment.

Murphy — considered one of the good guys at the jail by both inmates and other guards — said she wrote a report on the incident but that higher-ups told her it has disappeared. She’s trying to find a copy of it to submit again. Cpl. Jetsal said reports don’t go missing often at the jail, but “everybody loses things now and then. That’s just life.” Told of the missing report, Alford, a former Texas Ranger with more than 30 years in law enforcement, was livid. “That is simply inexcusable,” he said. He has had a new report drawn up and is investigating the incident. Murphy wouldn’t comment further on the behavior of Blankenship, who was recently promoted, but other guards said the incident was fairly typical. “Blankenship considers this his prison, just like he says,” said one guard, who asked not to be named. “And he does what he wants here.” The top jail administrator is frequently out on sick leave, the guard said, and with few other superiors around at night, Blankenship “is just the big bull on his shift.”

If Kiefer’s mistreatment in the restraint chair was, as Alford said, a “one-time incident,” that doesn’t explain a broader spectrum of abuse cases reported by inmates at the jail. Just in April and May, according to a jail source who asked not to be named, two pregnant women were placed in jeopardy; another inmate, known to be physically unsteady, was injured in falling from the top bunk in which she’d been placed; a guard had sex with a prisoner; and a patient with mental health problems died from eating paint chips. In one incident, a case of mistaken identity caused a seven-month pregnant woman to be placed in a maximum-security area. “She was kept there for several hours — in a potentially dangerous situation — despite the guard being told of her error,” said the source. The second pregnant inmate was placed in even more danger by a refusal of needed medical treatment, the source said. When the woman began hemorrhaging, other prisoners notified a guard, who took her to the nurse’s area. There, she was offered only Benadryl. She refused it and was returned to general population where she stayed until, hours later, a new nurse came on duty and had the woman rushed to the hospital, where doctors were able to stop the bleeding and save her fetus.

The same source also said guards repeatedly told one female inmate that her seriously ill father had died, which was a lie. The unsteady female inmate, who was put in a top bunk, fell a few minutes later and “slammed her head” on the floor, the source said. During the same period, a female guard was asked to resign after she had sex with a male trusty. A final incident listed by the source — of the inmate who died after eating paint chips — is “a mental issue and not a jail issue,” Alford said. “There is simply not adequate staff or equipment to put mental patients in our jails. Unfortunately we are being mandated by the state to take those patients when they’re arrested because [the Texas Department of] Mental Health and Mental Retardation doesn’t have sufficient facilities to hold these people.”

The same source also said guards repeatedly told one female inmate that her seriously ill father had died, which was a lie. The unsteady female inmate, who was put in a top bunk, fell a few minutes later and “slammed her head” on the floor, the source said. During the same period, a female guard was asked to resign after she had sex with a male trusty. A final incident listed by the source — of the inmate who died after eating paint chips — is “a mental issue and not a jail issue,” Alford said. “There is simply not adequate staff or equipment to put mental patients in our jails. Unfortunately we are being mandated by the state to take those patients when they’re arrested because [the Texas Department of] Mental Health and Mental Retardation doesn’t have sufficient facilities to hold these people.”

In fact, Alford said, if his staff notices obvious mental or physical problems they’re supposed to turn the arrestee away until they’ve received an OK from a hospital for that person to be placed in a general jail population. “Of course that decision is made when an arresting officer brings the suspect in, and sometimes people get through who shouldn’t,” he said. But the problem Alford’s facing goes far beyond MHMR’s lack of facilities. His jail is understaffed, and the pay levels so low that in one recent year, he said, “the turnover rate was almost 100 percent.” That means there is a constant stream of rookie guards, something Alford said is bad for the inmates and bad for Johnson County. However, both of the guards mentioned by name in the allegations by Kiefer and Norman B. were veterans. “Our jailers start at $24,458. After five years they still don’t reach $30,000. But each one of them has to take a three-week course to get their corrections officer’s license — and once they have that, they are a commodity,” Alford said. “They can go work for Tarrant or Dallas corrections” agencies. Starting pay in both Tarrant and Dallas is more than $31,000. “So we’re going to have some problems like you mention with so many new people all the time having to deal with not only a regular population but one that includes people with mental problems as well,” the sheriff said.

The problems related to medical issues, he said, were out of his hands, since the medical aspects of the jail are the responsibility of the Johnson County medical officer, Dr. Arthur L. Raines. The Texas Constitution makes sheriffs ultimately responsible for inmate healthcare at the county jails. But in the Johnson County jail, healthcare is run like a different department, with Raines applying for his own budget and staffing from commissioners. “I don’t want to get into a war with anyone,” said Alford, “but I don’t think the medical care is adequate at the jail. I don’t think it’s adequate in any jail in Texas.”

Tarrant County Sheriff Dee Anderson acknowledged both the responsibility that he and his colleagues across Texas bear on the issue of healthcare and the limits of their ability to carry out that duty. For sheriffs to be responsible for inmate healthcare without also being able to “hire or fire or discipline [medical staff] people, it leaves you in a position of negotiating for healthcare, which is a very difficult position to put any sheriff in,” he said. Raines, who doubles as Johnson County’s chief medical examiner, declined requests for comment, just as he did for the Weekly’s previous stories on Johnson County’s jail and law enforcement.

What ends up as a problem in Alford’s jail starts on the street, most frequently in Burleson, the county’s largest city, or in Cleburne, the county seat. Both cities have police departments at least twice the size of Alford’s 26-person squad of deputies. Other Johnson County towns, all with populations of less than 5,000, have much smaller police forces. In 2006, police in Burleson and Cleburne made a combined total of 4,400 arrests, of which Cleburne accounted for more than 3,100. In Cleburne, that’s the equivalent of more than 10 percent of the population getting arrested each year — a rate that raises eyebrows in other counties, especially since Johnson County’s major-crime rate is low. There was just one murder in Cleburne last year, 25 robberies, and 64 cars stolen. “Something is really off-kilter with those kinds of numbers in a small city like that,” said another Texas sheriff, who asked not to be quoted by name. “They must be looking to offset a budget shortfall with fines or something like that.”

Cleburne Police Chief Terry Powell did not return calls asking for comment on his department’s arrest figures. Other residents weren’t so reticent. Rice, the newspaper publisher, said Powell’s officers are extremely aggressive. “In general, the police in Johnson County will put you in jail for spitting on the sidewalk. They’ll call for backup and a sergeant when they stop a kid for a busted taillight,” he said. But he also noted that when Powell was named chief in 2002, “a lot of veteran officers left, and a lot of young guys came in who act like they got their training watching ‘Bad Boys.'” Alford agreed that policing throughout his county is fairly aggressive and said officers sometimes pick up people for offenses minor enough that “they shouldn’t even have been arrested.” As for Cleburne, he said only that Powell’s officers “do a good job of bringing people in, that’s for sure.”

One Cleburne mom said it’s nearly impossible to raise boys in the town “because the cops just want to put them down and pull them in. And once you’re in, you’re in the system. And you’ll never get out.” A former Sheriff’s Department employee noted that the Cleburne police sometimes don black masks to hide their faces and cover their badges during arrests. “The Cleburne cops get away with so much shit it makes me want to puke,” she told the Weekly. Burleson Police Chief Tom Cowan, who formerly held the same job in Cleburne, said he didn’t want to second-guess the decisions made by his former department or speculate on why Burleson police arrest people at only about half the rate of Cleburne, even though the two are roughly even in population. “There may be something to the fact that Cleburne is more of a stand-alone city while Burleson is really a suburb of Fort Worth,” he said. However, when Cowan was police chief in Cleburne — he left in 1999 — the department never neared the arrest totals it has reached under Powell.

In Burleson, a number of complaints about law enforcement are not about the police, but about Precinct 2 Constable Adam Crawford. The constable, an elected official not answerable to any police chief or sheriff, until recently made a habit of using his private, unmarked car, outfitted with a grill light, to make traffic stops — often at night on country roads, and often when the drivers were women. All the complaints made to the Weekly against Crawford, in fact, come from women. Alford and Johnson County Commissioners Don Beeson and John Matthews all knew of Crawford’s practice. Alford called the constable “a disaster waiting to happen.” Beeson called it “bad policing.” Beeson formerly served as a police chief in Keene and for the University of North Texas’ Health Science Center in Fort Worth. He also worked as a detective with the Johnson County’s sheriff’s department before being elected commissioner. “That was something that would never have happened anywhere I was a police chief,” he said.

Crawford assured the Weekly that the practice was legal and done by constables in many counties and said he simply preferred his own car to the marked cars provided by the county. However, constables in Hood, Parker, Tarrant, and Hill counties said that while the practice is indeed legal, it’s not normally done. “I’d have to wonder if the people of Johnson know what kind of a lawsuit they might face if something went wrong during one of those stops,” said one constable who asked that his name not be used. “I can do it, but I’ve never made a traffic stop,” said another. “We’ve got police and the sheriff to do that.” Commissioner Matthews, whose district includes Burleson, said Crawford is no longer making his late-night plain-car traffic stops. “That practice has been stopped,” he said.

Crawford assured the Weekly that the practice was legal and done by constables in many counties and said he simply preferred his own car to the marked cars provided by the county. However, constables in Hood, Parker, Tarrant, and Hill counties said that while the practice is indeed legal, it’s not normally done. “I’d have to wonder if the people of Johnson know what kind of a lawsuit they might face if something went wrong during one of those stops,” said one constable who asked that his name not be used. “I can do it, but I’ve never made a traffic stop,” said another. “We’ve got police and the sheriff to do that.” Commissioner Matthews, whose district includes Burleson, said Crawford is no longer making his late-night plain-car traffic stops. “That practice has been stopped,” he said.

Despite the opposition of the commissioners to Crawford’s traffic-stop tendencies, and despite Alford’s attempts to clean up his jail, Johnson County residents apparently have a high tolerance for what some prefer to call “aggressive policing.” “The truth is our people — and I’m talking for Cleburne, but it probably extends over the whole county — want aggressive policing,” said Cleburne Mayor Tom Reynolds. He told a story to make his point. “I turned 50 a few years ago and bought myself a new Corvette,” he said. “And I’d gone out to Rio Vista to buy a six-pack — that was the only place to get beer in this part of Johnson County then. “Well, I put it in the trunk and opened a bottle of water and took a drink as I was leaving the parking lot. And just at that moment a state highway patrol car flew by in the opposite direction. In a few minutes, just as I was about to enter Cleburne, here comes that car up behind me with its lights flashing.”

He pulled over, and the two officers approached his car. He asked why he’d been stopped; they asked him if he’d been drinking. He said he hadn’t and showed them the water. “They told me they had a video of me crossing the white lane-lines five times. I told them they certainly did not because I hadn’t crossed the line.” A few minutes later Reynolds was told he was free to go. While most people would probably be angry at having law enforcement officers try to intimidate them with a story of a nonexistent video, Reynolds wasn’t. “Now that’s what I call good police work,” he said. “Good aggressive police work.” Was it improper intimidation by the officers? “Maybe where you come from. Here we call that zealous protection of the public,” he said.

And the public, at least in Cleburne, won’t stand for crime, said Reynolds. “Cleburne is the quintessential blue-collar city. We’re not very sophisticated here, many folks are older, and they’re conservative. They want police, prosecutors, and judges to be harsh with lawbreakers. And if you’re a politician or a judge and you don’t agree with that, well, you’re not going to get re-elected.” He named a Hill County town that he described as “sort of lawless, like an old Texas town of 100 years ago. … There are a lot of people who make meth down there. But they don’t bring it to Johnson County. If you want it, you drive down to Hill County to get it. I guess their feeling is that they have a much better chance of getting off in Hill than they do in Johnson.”

Chief Cowan said there’s a similar feeling in Burleson, which straddles the Johnson-Tarrant county line. “We don’t keep a record of it, but my gut feeling is that those people arrested on the Tarrant side — who then go to court in Tarrant — might be treated more leniently by the courts than those arrested on the Johnson side. I think you might say that the people of Johnson hold their people to a higher standard than in some other places.” A lot of the dopers and thieves and others arrested in Johnson County probably belong in jail, Rice said — but a lot of them probably don’t. “Maybe a lot of them should just be reprimanded,” he said. “But you’ve got the police out there arresting everybody, so there’s a backlog at the court, and a lot of the people with small dope cases or whatever wind up sitting in the county jail for months. And when they finally get a lawyer — and a lot of [lawyers] have no spines out here — they tell the kid the judge is tough, and so they agree to a plea bargain, and the district attorney will go along with that. But then they get on probation and go get some dope and end up back in and out of jail and drug programs for the length of their sentence. “Anybody can see the system is broken,” he said. “You think about some kid who sits in jail for months, and when he gets out his family’s mad at him, he’s broke, his girlfriend left him, he’s mad as hell, and as soon as he’d got $10 or $20 he’s going straight to the crack house.”

Commissioner Beeson said several criminal-justice issues need addressing in Johnson. “Part of the problem is that we don’t have a public defender’s office,” he said. “What we use are court-appointed attorneys. And the problem with court- appointed attorneys is that they get paid so little they often ask for continuances. … And judges generally want to grant continuances when a lawyer says he’s not ready. Now that results in people often spending months in jail needlessly. “Then you’ve got overzealous police — not all of them, but enough. When I was an officer, I used to think everybody belonged in jail. Now that I’m a commissioner, I’m beginning to think that only the worst offenders belong there. The truth is, we’ve got a whole lot of people in jail who maybe don’t all belong there.”

The Johnson County jail is a drab brick building surrounded by a double fence topped with razor wire. A recent addition of 284 beds brings its total to 777. The new beds were intended to house inmates from other counties with the idea that Johnson could make some money from them. In fact, Alford said, there are rarely as many as two dozen out-of-county inmates, yet the jail operates nearly 95 percent full. So the new beds have been taken by people arrested by Johnson County law enforcement agencies. “And if they added 300 more beds, they’d be filled in no time,” said a former guard who still works for the county. “Heck, they could add 1,000 more beds and they’d be filled.” Alford, meanwhile, has a lot harder time filling up his roster of jail guards. And since the guard ranks turn over so frequently, the situation continues to be difficult both for the county and the inmates.

One former female guard, who spent more than five years as a jailer, said she finally quit because she couldn’t stand to witness any more inmate abuse by jailers and police and because of the lack of medical staff. “There were things done to some of those inmates that were just wrong. And the medical was a joke. In all my years there I saw Dr. Raines less than an average of once a year, and I never saw another doctor there at all. We’d have X-ray specialists in once in a while, but that was it. No night nurses, nurses on staff who weren’t nurses at all, no counselors for people with mental health problems. I remember one 17-year-old kid we had who was arrested for slapping his teacher. He had the mind of a 7-year-old. And he sat for months and months in that jail before he could be moved to a home where he could be cared for.” Inmate letters to the Weekly routinely note that the jail is simply unfit for many of its inhabitants. One prisoner wrote recently that she’d finally gotten her transfer to a state prison, “and I am the happiest person in the world to be getting out of this place.”

Alford doesn’t think his jail is any worse, and is probably better, than most county jails. “We’re a good county. And we’ve got good people working for the jail for the most part,” he said. “Of course we make mistakes, we get bad apples, but when we find out about them we get rid of them. And it being a jail, well, some bad things are going to happen; we just try to keep them to a minimum.” What would be needed to improve jail conditions? He didn’t hesitate. “We could change things for the better if we had more staff, proper training and more pay to keep them on board,” he said. “That would make a difference.”

Another former female guard said the criminal justice system in Johnson County will never be fixed until “we have people in Johnson who will stand up — to the police, the jail guards, even the district attorney — and demand a change. Half the guards probably belong in jail, and I know half the police do. But the people here like it like it is.”

You can reach Peter Gorman at peterg9@yahoo.com.