Cows grudgingly rise from mid-morning naps as Billy Mitchell’s Ford F-250 jostles down a dirt road past the oak trees he climbed as a kid.

The oaks are massive, some with trunks as wide as his pickup. His parents bought this parcel of land 40 years ago, back when he was 9. The Trinity River runs deep and wide through his 70 acres near Aledo, with a large pasture and a 130-year-old farmhouse that still provides solid shelter. The place is special, and his voice sounds hurt and his face turns red as he talks about how a gas company used eminent domain laws to cut a 25-foot swath across the middle of his property to bury a pipeline, touching off a two-year battle that cost him about $100,000 in legal fees. “I’m devastated,” he said. “It’s un-American. Private companies shouldn’t be able to take land by eminent domain just so they can make more money for themselves. It makes me sick.”

The oaks are massive, some with trunks as wide as his pickup. His parents bought this parcel of land 40 years ago, back when he was 9. The Trinity River runs deep and wide through his 70 acres near Aledo, with a large pasture and a 130-year-old farmhouse that still provides solid shelter. The place is special, and his voice sounds hurt and his face turns red as he talks about how a gas company used eminent domain laws to cut a 25-foot swath across the middle of his property to bury a pipeline, touching off a two-year battle that cost him about $100,000 in legal fees. “I’m devastated,” he said. “It’s un-American. Private companies shouldn’t be able to take land by eminent domain just so they can make more money for themselves. It makes me sick.”

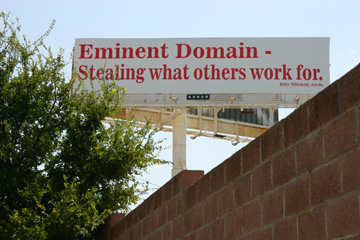

Mitchell wanted his day in court but agreed to a settlement, citing escalating legal costs and aggressive tactics used by the gas company. Feeling cheated and bullied, the Fort Worth native rented a billboard alongside I-30 near Hulen Street for the entire month of August. Emblazoned in large red letters against a white background, his message was clearly seen by thousands of passing motorists: “Eminent Domain — Stealing What Others Work For.” The billboard lists his name and residence but not his phone number. Still, dozens of people have tracked down his number and called to thank him for pointing out the unfairness of eminent domain. “These are people facing different issues than gas pipelines — Trinity River development, the Trans-Texas corridor, a lot of different issues — but they still call,” he said.

Cities have long had the ability to take land to build airports, roadways, utility easements, lakes, railroads — even mall parking lots. And they’ve reaped unexpected benefits. Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport is raking in many millions of dollars from mineral rights that were acquired by the cities of Fort Worth and Dallas in the 1960s and 1970s using eminent domain and the threat of it. Nowadays, people are getting smarter. They’re playing hardball with developers, natural gas drillers, and city officials who typically want to pay as little as possible when seizing land. They’re encouraging state legislators to make it harder for cities and counties to take land for private commercial development. They’re educating themselves, joining forces, and hiring specialty lawyers.

The first time Jim Vreeland faced eminent domain was in the late 1990s when he learned that his warehouse on Vickery Street was in the path of the planned Southwest Parkway. Knowing the city had a legal right to take his land prompted Vreeland to sell without much of a whimper. He wasn’t angry; he viewed the parkway as a legitimate public works project. He and the city settled on a price amicably. By then, he had purchased a new office building in an industrial district just north of downtown. But before long, he was in the way of another planned project — Trinity River Vision, with its river channel and a small lake expected to create a demand for condos and retail near downtown. City officials and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers call it flood control, but it doesn’t take a genius to see it’s actually a private economic development project relying on eminent domain powers to obtain land. This time around, Vreeland isn’t as willing to hand over his property without a fight. “I bought this property under the shade of the Fort Worth skyline for a reason,” he said. “I bought this as an investment. Now somebody else wants to take this and they will realize the increase in value.”

Municipalities have a huge advantage in these types of land seizures. Besides favorable federal, state, and local laws, they also rely on legal help paid for by taxpayers. “Usually that kind of entity will have better lawyers than the individual landowners,” said Bob Lukeman, another business owner whose property is in the way of the Trinity River Vision. Even when governments and utilities don’t actually condemn property through eminent domain, it remains a powerful tool for scaring property owners into accepting what they often characterize as low-ball offers. The vast land purchases that made way for D/FW Airport effectively pitted city officials, experienced landmen, and savvy lawyers against hundreds of rural property owners who might not have realized they were signing away mineral rights when they sold out. The cities of Fort Worth and Dallas used the threat of eminent domain or actual condemnation to force land sales, acquiring 16,950 acres between the late 1960s and 1975. Obviously, the airport is a legitimate public works project that has been a long-term economic engine for North Texas, but the cities went beyond taking surface rights. They obtained mineral rights as well by inserting the words “fee simple” into the deeds, a legal phrase that refers to absolute ownership of real property, including minerals. “None of these documents are going to have a separate listing of mineral rights, none are going to specify that separately because ‘fee simple’ means everything,” D/FW Airport legal counsel Paul Tomme said.

Technology that has made horizontal drilling possible and created the local natural gas boom in the Barnett Shale formation wasn’t around back when the airport land was being acquired. Fair market value was based on surface land values. While it’s doubtful either side anticipated the gold mine that mineral rights and natural gas would one day represent, the cities were smart enough to sweep them up anyway — a move expected to pay off hugely in coming years. When Chesapeake Energy Corporation paid $185 million and promised 25 percent of gas royalties to drill at the airport last year, none of the original property owners shared in the sudden wealth. George G. Wilkes was Fort Worth’s land manager back then and was responsible for overseeing crews that approached landowners with offers. He retired 20 years ago but still recalls knocking on doors and negotiating with landowners. Few were happy about being ousted for an airport. “Three out of four didn’t invite us in eagerly,” he said. “There weren’t any really large landowners as I recall. About 15 or 20 acres was the norm, mostly small rural farms.”

Few people back then mentioned mineral rights or asked that the potential worth of minerals be included in the fair market appraisals on which payments were based. “I daresay, nine out of 10 people wouldn’t even know what you were talking about with mineral rights,” he said. Morris Matson was assistant city manager during that time. He processed paperwork and attended eminent domain trials when landowners and the cities couldn’t agree on fair market value. Many landowners felt ripped off, but Matson doesn’t recall any of them insisting on keeping their mineral rights. Looking back, he questions whether the city had a real moral basis for taking the subsurface ownership. “How could you say that condemning mineral rights that are thousands of feet under the ground was necessary to build an airport?” he said. “In my opinion, we had no moral right to condemn those minerals without making sure the landowners were told that we were taking the minerals.”

Grapevine Mayor William D. Tate, an attorney, represented about 20 property owners in the airport land grab and doesn’t recall any of them seeking to keep mineral rights. After all, there were no gas leases, no mining, and no oilfields out there. Still, when the state highway department took land for highways, that agency didn’t seek mineral rights, he recalled. “Whoever gave up the right of way for the highways still [owns] the minerals under it,” he said. Those who lost mineral rights might be upset, but he doubts any of them could win them back in a court case. “It seems very unfair now,” he said. But, “It would be a tough battle 30 years later.” Lawyers could have a field day battling these issues in court, but most of the time the government wins. Property owners sued the city of Austin and the Lower Colorado River Authority after their land was taken in 1975 to make way for an electric generating plant. Six years later, the city and river authority leased the mineral rights to oil and gas drillers. The property owners sued the municipalities for fraud and misrepresentation, saying they weren’t told of the potential value of the minerals, and claiming the city lied about its right to take the minerals. The Texas Court of Appeals overruled, citing a two-year statute of limitations on suits for fraud damages.

Grapevine Mayor William D. Tate, an attorney, represented about 20 property owners in the airport land grab and doesn’t recall any of them seeking to keep mineral rights. After all, there were no gas leases, no mining, and no oilfields out there. Still, when the state highway department took land for highways, that agency didn’t seek mineral rights, he recalled. “Whoever gave up the right of way for the highways still [owns] the minerals under it,” he said. Those who lost mineral rights might be upset, but he doubts any of them could win them back in a court case. “It seems very unfair now,” he said. But, “It would be a tough battle 30 years later.” Lawyers could have a field day battling these issues in court, but most of the time the government wins. Property owners sued the city of Austin and the Lower Colorado River Authority after their land was taken in 1975 to make way for an electric generating plant. Six years later, the city and river authority leased the mineral rights to oil and gas drillers. The property owners sued the municipalities for fraud and misrepresentation, saying they weren’t told of the potential value of the minerals, and claiming the city lied about its right to take the minerals. The Texas Court of Appeals overruled, citing a two-year statute of limitations on suits for fraud damages.

In another landmark case dating back to 1929, the city of Abilene used eminent domain to condemn 56 acres belonging to I.N. and Elma Jackson, to make way for an airport. Many years later, the city abandoned the airport. Elma Jackson later appealed the condemnation, saying the city had no right to fee-simple title under condemnation, but in 1955, the state Court of Civil Appeals ruled in Abilene’s favor. Much more recently, former landowners in Kentucky sued the federal government on similar charges. They were awarded $32.5 million in 2005, although they haven’t collected any money and the case continues to work its way through the judicial system. “Right now it’s in a stalemate,” said William T. Griggs of Morganfield, Ky., whose family’s 250-acre farm was taken for a military base during World War II but was later mined for coal. Griggs was 18 when his family was forced from their farm. Now he’s 83 and one of a number of neighbors who filed the class-action suit, saying they weren’t told they were giving up their mineral rights and shouldn’t have had them taken from them. “My folks asked them about the mineral rights and they [federal officials] said, ‘We’re not interested in the mineral rights,'” Griggs said. Those mineral rights bagged the government about $35 million for oil and coal leases. “You want to think your government will treat you right, but the government will cheat you just as quick as anybody I know of,” he said. “I was in World War II and gave three of the prime years of my life and put my life on the line for this country, and I’d do it again, but it makes you bitter when you realize that they done us like they done us.”

A court dismissed the lawsuit in the 1960s. But they were granted a hearing in a federal claims court decades later. In 2005, Judge Susan Braden awarded them $32.5 million in a preliminary ruling. She encouraged both sides to settle and installed former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor to mediate. Those talks have since broken down.

“Our lawyer just said they didn’t have any news for us and as soon as they did, they’d tell us what was going on,” Griggs said. “I’m just as in the dark as you are.” Fort Worth probably wouldn’t have secured any mineral rights at the airport if the land were being purchased today. Nowadays, owners know better than to give up mineral rights for nothing. Lawsuits in the 1970s and 1980s contested the government’s right to take mineral rights through eminent domain, and municipalities now focus mostly on surface rights, said John Baen, a University of North Texas real estate professor and condemnation expert. Contracts must spell out whether mineral rights are being taken, and, when the subsurface rights are taken, municipalities must pay the fair market value.

Property owners in the path of the Trinity River Vision or the Southwest Parkway will enjoy any profits from the current natural gas boom because they now know to retain their mineral leases. City officials have said they are not seeking mineral rights when buying land for either of those projects, and state officials said the same about land required for the Trans-Texas Corridor, a planned tollway across the state. These days, when gas drillers or city officials start eying their communities, Fort Worth property owners start holding meetings, discussing options, and forming coalitions. Many of the 95 property owners in the path of the Trinity River Vision have collectively hired Corsicana-based attorney Glen Sodd, who specializes in eminent domain issues and oil and gas law. “Property owners will drive a harder bargain for themselves based on this knowledge,” Lukeman said. “There is now a track record of what these minerals will yield, and if somebody is going to purchase by force a certain amount of property, they must buy those minerals if the property owner is wise enough to insist on that.”

In many ways the system is set up for the governments and utilities to beat out the little guys. At least for now. But change is looming. A 5-4 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005 angered many people who consider private property rights to be sacred. The U.S. Constitution’s Fifth Amendment protection against gratuitous governmental interference says property shall not be taken for public use without just compensation. The dispute lies in determining what constitutes “public use” and “just compensation.” Kelo vs. City of New London made it clear that at least five Supreme Court justices didn’t view property rights as sacrosanct. In that decision, the Supreme Court majority ruled that a government can take property and bulldoze homes and buildings to make way for private economic development. Their reasoning: If the new development results in larger tax bases and more jobs, then it’s for the public good. A majority of Americans have some questions about the fairness of taking someone’s property to build a mall that might or might not succeed.

The decision outraged many, and O’Connor, who was on the Supreme Court but voted in the minority, warned that the ruling bowed to the influential and would embolden local governments to seize land to make way for pet projects. (Arlingtonians, say hello to the Dallas Cowboys.) Justice Clarence Thomas predicted the decision would most affect poor communities and the politically powerless. “Before the Supreme Court decision, cities already regularly abused the power of eminent domain,” Dana Berliner wrote in Opening the Floodgates: Eminent Domain Abuse in the post-Kelo World. The report was compiled in June 2006 for the Institute of Justice, a nonprofit public interest law firm based in Arlington, Va. “But Kelo has indeed become the green light that Justice O’Connor and Justice Thomas warned of in their dissents.”

On the other hand, the decision created a groundswell of opposition that in some cases has led to states passing measures to rein in abuses. Some states already forbid using eminent domain for private development unless it eliminates blight. Texas ain’t one of ’em, as Gov. Rick Perry proved earlier this year when he vetoed a bill designed to give more protections to landowners.

Perry vetoed the bill (HB 2006) after an amendment was added that city and county officials said would increase the cost of acquiring land for roads and highways by at least a billion dollars a year and open the door for condemnation lawyers to file suits — at taxpayers’ expense — for diminished access to properties. “We supported the bill up until an amendment got put in that … could have halted any kind of urban expansion in its tracks,” the governor’s spokesman, Robert Black, said. “Every major city in the state came out and begged us to veto it.” The amendment was added late in the session, and Perry warned legislators that he didn’t support it.

Perry vetoed the bill (HB 2006) after an amendment was added that city and county officials said would increase the cost of acquiring land for roads and highways by at least a billion dollars a year and open the door for condemnation lawyers to file suits — at taxpayers’ expense — for diminished access to properties. “We supported the bill up until an amendment got put in that … could have halted any kind of urban expansion in its tracks,” the governor’s spokesman, Robert Black, said. “Every major city in the state came out and begged us to veto it.” The amendment was added late in the session, and Perry warned legislators that he didn’t support it.

However, the bill’s author, State Rep. Beverly Woolley, a Republican from Houston, wouldn’t remove it, telling a Houston reporter there wasn’t enough time left in the session to change the wording.

Many lawmakers, including State Rep. Phil King, a Weatherford Republican, liked the bill and said it made eminent domain more equitable for property owners.”If that’s what their property is worth, that’s what the government should be paying,” King said. “The government is not supposed to get a discount on these deals.” Legislators will pass an eminent domain bill next session, he predicted.

“Property rights are one of the most fundamental elements of our way of life, and if the government is going to take property away from you against your will, they better have a really good reason for doing it, a very important matter for the whole public, and they better pay you what it’s really worth,” King said. “As a general rule neither of those things is required [currently].” Case in point: Billy Mitchell’s fight against Empire Pipeline Corporation. Mitchell is the Fort Worth native whose acreage near Aledo includes the 70 acres pinpointed by a natural gas driller as an ideal spot to bury a gas pipeline. Mitchell is not anti-drilling. He’s leased his property to drillers, currently has two working gas wells on his property, and has enjoyed the revenues. But a drilling company that had leased his mineral rights in turn leased them to Empire, a company based in Lebanon, Mo. Pipeline companies have eminent domain powers, and Empire decided to cut a swath across the middle of his property. The company offered Mitchell $17,000 for the easement, which Mitchell thought was but a fraction of the worth of the damages he’d be enduring. But he quickly realized that a large company with a staff of lawyers, unlimited resources, and eminent domain powers is pretty near unbeatable.

Empire condemned more land than was necessary, Mitchell said, and then refused to let him build an improved road across the pipeline, effectively cutting him off from half of his property. “They used the tactic of denying me access to half of my property as a negotiating tool to get my land at a cheap price,” he said. He accused the pipeline workers of purposely leaving his gates open to let his cows loose on public roads. He accused company lawyers of using delaying tactics to run up his legal costs. After two years of wrangling, Mitchell gave up and agreed to a settlement — $117,000. When his lawyers had been paid, however, Mitchell ended up with only $17,000 — Empire’s original offer. Worst of all, he said, the whole ordeal could have been prevented if Empire had simply transported its gas through nearby pipelines owned by other companies. State law allows pipeline companies to use eminent domain to build new pipelines rather than sharing existing lines owned by other companies. Why? To maximize profits for each company, regardless of the inefficiency of running numerous pipelines for the same purpose.

“If landowners had the same powerful lobbyists that pipeline and oil companies do, they would get legislation passed to makes these companies share pipelines,” said Sodd, who represents not only landowners affected by the Trinity River Vision but also those in the path of the Dallas Cowboys stadium, and numerous others who have complained of being gouged by gas drillers and pipeline companies. “It would be cheaper for the companies to all share one pipeline, but they don’t trust each other, and nobody is requiring them to be efficient in the number of pipelines they use.” Mitchell encouraged Empire to use existing lines or at least bury its new lines in an existing easement. No deal. “They wanted to blaze a new trail right across my property,” he said. “And they wanted to use me to show other people what happens if you fight them. If we hadn’t have settled, I would have been in bankruptcy.” Empire officials did not return calls for comment on this story.

“If landowners had the same powerful lobbyists that pipeline and oil companies do, they would get legislation passed to makes these companies share pipelines,” said Sodd, who represents not only landowners affected by the Trinity River Vision but also those in the path of the Dallas Cowboys stadium, and numerous others who have complained of being gouged by gas drillers and pipeline companies. “It would be cheaper for the companies to all share one pipeline, but they don’t trust each other, and nobody is requiring them to be efficient in the number of pipelines they use.” Mitchell encouraged Empire to use existing lines or at least bury its new lines in an existing easement. No deal. “They wanted to blaze a new trail right across my property,” he said. “And they wanted to use me to show other people what happens if you fight them. If we hadn’t have settled, I would have been in bankruptcy.” Empire officials did not return calls for comment on this story.

New versions of Mitchell’s nightmare are being played out in courts every day. The system is set up to favor the rich, in part, Sodd said, because legal costs and out-of-pocket expenses are not recoverable in condemnation cases.

“It’s hard for most people to go through these fights,” he said. “They are long, drawn out, difficult, and expensive. As a result it’s difficult on people when they receive unfair offers.” For example, say a company wants to put a pipeline across your property, uses eminent domain to get access, and then offers you a low-ball price of $5,000 for the easement but no revenue from the pipeline. That leaves you two options: Take the offer or go to trial. A trial means spending thousands of dollars on attorneys, appraisers, depositions, and any number of legal necessities. In trial, a jury rules in your favor and you’re awarded $50,000 — 10 times the original offer. But you’ve spent $100,000 in legal fees, meaning you end up $50,000 in the hole — even though you won your case in court.

Sodd has represented property owners in similar cases for the past 35 years and frequently sees government entities make low offers to landowners, even though the law requires paying fair market value. Arlington wanted Evelyn Wray’s house and prime frontage property on Randol Mill Road for the Cowboys stadium, five acres that had been in her family for years. The city threatened eminent domain and offered $375,000, the approximate value based on Tarrant Appraisal District records but far short of its commercial potential. The elderly Wray rejected the offer, hired Sodd, and eventually settled for $2.75 million. But lawsuits involving many other Arlington property owners with smaller parcels are still pending.

“People are expressing those frustrations to legislators,” the attorney said.

That’s no guarantee of change. The state is one of the primary condemners of property, and getting legislators to pass laws making it more difficult for counties, cities, and the state’s own agencies to grab land hasn’t been easy. This year’s session was a landmark in that sense, although reforms ultimately fizzled under Perry’s veto. “It would make it too expensive for his pet project, the Trans-Texas Corridor,” Sodd said. “Rick Perry is the landowners’ worst enemy in Texas. Rick Perry thinks its OK to cheat landowners and offer them low prices.” Sodd can’t predict whether reactions over Perry’s veto and local issues such as Trinity River Vision will prompt further legislative pressure. But change seems as likely now as at any time in his long career. “It’s become much more of an issue in the past five years, and the Kelo decision really outraged people,” he said. “Now it’s become a political issue.”