Little Rooster wasn’t a hero. He was a small-town constable who always wanted to play cop.

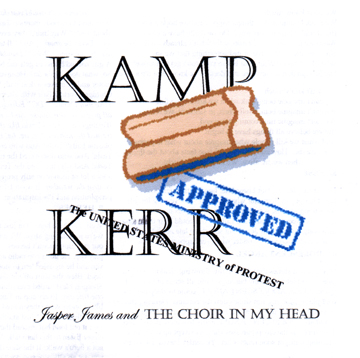

Got himself a scanner and listened to it constantly. One day, he stopped a stolen van and was fatally shot. “Little Rooster” was what all of the real cops called him, under their breaths. But on the day of his funeral, all of a sudden he was “hero.” Not just another senseless, unnecessary death. A hero. James Michael Taylor’s got a problem with hero worship. Little Rooster is just one of a few examples on Kamp Kerr Approved: The United States Ministry of Protest, singer-songwriter Taylor’s new, rabid album. “When you save your own skin, it’s not a hero’s walk,” he sings in his high, trembling voice on “Heroes.” “If the shoe don’t fit, you don’t call it a sock / … It don’t take a hero to say no to the draft / … And you don’t take my freedom and give it to Iraq.”

Got himself a scanner and listened to it constantly. One day, he stopped a stolen van and was fatally shot. “Little Rooster” was what all of the real cops called him, under their breaths. But on the day of his funeral, all of a sudden he was “hero.” Not just another senseless, unnecessary death. A hero. James Michael Taylor’s got a problem with hero worship. Little Rooster is just one of a few examples on Kamp Kerr Approved: The United States Ministry of Protest, singer-songwriter Taylor’s new, rabid album. “When you save your own skin, it’s not a hero’s walk,” he sings in his high, trembling voice on “Heroes.” “If the shoe don’t fit, you don’t call it a sock / … It don’t take a hero to say no to the draft / … And you don’t take my freedom and give it to Iraq.”

Taylor clearly is treading the slippery terrain of semantics, but in an era in which the medium, per Marshall McLuhan’s decades-old adage, is the message, parsing the definitions, usages, and even sounds of words is serious business. Veteran Taylor, who seems to drop a full-length album every other week, is good at sinking his teeth into words and also ideas. Credited officially to a new name for Taylor’s one-man band — Jasper James and the Choir in My Head — the album is a long, continuously surprising listen. The arrangements consist mostly of drum tracks, some studio gimmickry, and Taylor’s acoustic guitar. Maybe the best way to describe his music is to tell you what it is not. It is not rock, rap, country, folk, or jazz. Nor is it a little of all five. Rather, it is what it is: an older guy equipped with an acoustic guitar, drum tracks, an aptitude for production, and a lot of ideas.

The condition of the country is Taylor’s wellspring. He tackles everyday deaths to illuminate their shared source: Big Issues. Corny? Maybe, but for every flat note or flat thought, there are a dozen revelatory expressions. “We Don’t Know Much” is a good example. “When we pray, are we just asking for what’s already on its way? / Now, tell me, is that true or just something that we say? / When Dad says, ‘Wear your hat so you won’t get sunstroke’ / Did he read that somewhere and doesn’t he know that it’s a joke?” The truth, even in our mass-media-saturated age (or maybe because of it), has never been more elusive. Al Gore says one thing about the environment; a line of people on the other side of the aisle says the opposite. Dubya says one thing about the war in Iraq; a line of people on the other side says the opposite. Osama bin Laden says one thing about the afterlife; Pat Buchanan says the opposite. Somewhere in the gaping canyon between the points and counterpoints is the truth. Or, rather, a single truth: that the truth — as we tend to define it — is a moving target. Remember:

What may look peachy-keen to China or France may not look peachy-keen to us. The result is that we’re left with two options: Do our own research and figure out everything for ourselves, which would take a million lifetimes and still never be absolute, or stick to the basics as neatly summarized in Taylor’s “Shoes”: “And should it be a bother for a father to teach his son / ‘Son, there are things that we do not do / And, son, there are games we do not play / And you don’t point guns at people when we are at work or at play / And you don’t follow your buddy when it’s clear he’s lost his way / And you don’t make others suffer because you are afraid.’” Sticking to the obvious constitutes Taylor’s entire plan of attack. As most of us probably know, sometimes the right thing to do is so painfully clear that we can’t bear to watch other folks ignore it or pretend that it doesn’t exist to save their own skins or ways of life. Taylor says we have corporatized education to thank for the ignorance around us. His song “Tesla” is about the titular famed inventor whose work is rarely taught in schools because doing so might nullify received wisdom. For the fearful, Taylor indicts a free market system that is powered almost solely by blue-collar blood. “Sometimes,” Taylor sings on “Adolescent Angel,” “as the day progresses she gets swept up in the race / Morning sunlight soon renews her / Yesterday leaves not a trace / Could an adolescent angel be the spirit you convey?”

Some of Taylor’s musicmaking borders on the amateurish. His “rapping” on “Palmdale, California 1951” is embarrassing to listen to, and, even though “Tesla” is a toe-tapper, on the vocal parts where Taylor should be ironic he’s deadly serious. The discrepancy is jarring. Taylor is at his best when he’s either outright silly or solemn. “Little Boys Love Baseball” is a pretty, sparse, easygoing ballad, and “If You Left Me,” written with Lisa Aschmann, is a cute, bluesy haunt: “If you left me, I’d buy a batch of oopsy paint and mix it right here in the sink / And I’d paint out all your colors, and I’d paint out all your smells / Paint whiskers on all your pictures / Have my way with your pastels.” There’s no doubt that James Michael Taylor is an acquired taste. But he does have something to say. He can turn a phrase, and his ideas, while astringently left of center, consistently seem to be unique to him and occasionally downright enlightening. Visit JamesMichaelTaylor.com.