Smug.”

“Literal.”

“Impervious to multiple interpretations.”

“Susceptible to parody.”

“Self-parodic.”

“The Old Guard’s new clothes.”

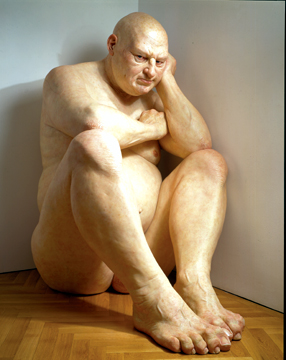

And there you have just a few of the thoughts that popped into my head at the Ron Mueck exhibit at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. The fiftysomething Australian makes hyperrealistic and impossibly lifelike figurative sculptures that vary widely in shape and scale. Some of them sit or lie, and some crouch or curl up. Some of his infants are as large as compact cars, and some of his adults are as small as a pair of work-boots. “I change the scale intuitively, really, avoiding life-size because it’s ordinary,” he has said. “There’s no math involved.” Originally presented by Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Paris, the exhibit may go down as the Modern’s most successful touring show ever. Last month was the museum’s best July on record. The number of visitors topped out at about 31,000. If history is any indication, attendance figures will stay high through October, when the show packs up and ships out.

And there you have just a few of the thoughts that popped into my head at the Ron Mueck exhibit at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. The fiftysomething Australian makes hyperrealistic and impossibly lifelike figurative sculptures that vary widely in shape and scale. Some of them sit or lie, and some crouch or curl up. Some of his infants are as large as compact cars, and some of his adults are as small as a pair of work-boots. “I change the scale intuitively, really, avoiding life-size because it’s ordinary,” he has said. “There’s no math involved.” Originally presented by Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Paris, the exhibit may go down as the Modern’s most successful touring show ever. Last month was the museum’s best July on record. The number of visitors topped out at about 31,000. If history is any indication, attendance figures will stay high through October, when the show packs up and ships out.

The magnitude of the response is appropriate. The exhibit is brilliant. The way it is installed, with plenty of breathing room between the pieces, is brilliant, and all 13 of the pieces are brilliant. So brilliant, in fact, that I still cannot wrap my head around them. I am still having trouble letting my defenses down and conceding that the show may be one of the strongest aesthetic experiences I have ever had; that it is bigger than me, bigger than you, bigger than truth! OK, maybe not that big, but still: Staring into the face — literally — of immortality, of death, of being embalmed, of being captured in photographs and frozen neatly in place for eternity, naturally, put me on the defensive. Some of the other phrases I muttered at the Modern are too colorful to repeat here.

We are a culture of howevers and buts. “The movie was great, but Jack Nicholson chewed the scenery.” “The lasagna was great, but Jack Nicholson put too much grated parmesan on top.” “The sex was great, but Jack Nicholson kept peeking in to check on us.” Being somewhat suspicious of excellent things is vital to our survival, and many of us are mistrustful, perhaps rightfully so, of contemporary art — we don’t want some fancy damn Yankee Abstract-Expressionist pulling our denim-covered legs. But healthy suspicion can lead to whining for whining’s sake, and whining for whining’s sake is often a symptom of our grave dissatisfaction with the goods and services we buy, use, and discard daily. We have grown so accustomed to complaining about the inadequacy of stuff that we reflexively question the good. Plus, as the old saying goes, you can piss on anything.

Well, I was going to piss on the Mueck show but then thought, “What’s the point? I can say his pieces are powerfully inert, or that the size of the pieces appears to be random, or that they offer more insight into the artist than into the human condition, but so what? They are fun, they are communicative, and they are life-affirming.” So instead of draining my purported qualms upon the fleshy genius at the Modern, I’m opting to focus on the good, starting with the quality of craftsmanship. Mueck captures flesh tones, folds of skin and its texture (down to the pores and blue veins), and facial and bodily expressions with such precision that you may feel compelled to reach out and touch a toe or an arm or eyeball just to be sure. Perhaps to quash any such temptation, the show is accompanied by a short film about Mueck’s processes, from conceptualization to formation to finish. At one point, we learn that he sews the hair into his figures’ skulls — and there is a lot of hair — strand by strand. He doesn’t explain his work or his reasons for doing it, which is a plus. His silence has a couple of different layers to it: a.) Good art doesn’t have to explain itself, b.) artists are artists, not critics, especially of their own work, and c.) explaining or explaining away art is my job.

Mueck started out in children’s television and film as a model-maker and puppeteer. He didn’t get into fine art until about 10 years ago, when he collaborated with his mother-in-law, Paula Rego, on one of her pieces. Gallery owner and advertising mogul Charles Saatchi saw the show and, smitten by the younger artist’s creations, began collecting and commissioning work from him. The following year, Mueck participated in the controversial group show Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection at the Royal Academy. His pieces now sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. There is no way around his story. His background as a passionate craftsman who backed his way into the vile art world informs our perception of him. He’s just a normal guy who makes art not because he wants to but because he has to. What else explains his works’ appeal for kids and adults? What else explains a grown man devoting countless hours to sewing hair into giant skulls? His perseverance, manifest in the folds of skin and flesh tones and hair follicles, may bespeak one crazy dude. But its sheer excellence bowls you over and, in doing so, invites a confrontation that may end in either fearful ambivalence or gracious acceptance, depending on where you stand. Or sit, crouch, or lie.-Anthony Mariani

Ron Mueck

Thru Oct 21 at 3200 Darnell St, FW. 817-738-9215.