Mornings begin with a trip to his spacious office and compiling a list of things to do. Days are spent knocking things off the list — from teaching chores to working on books and articles, to taking phone calls from former constituents asking for help, even though Jim Wright hasn’t been an elected official in almost 20 years.

Other calls come from current politicians, such as Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief, tapping into the connections and expertise Wright gleaned over 34 years in Congress. Then there are the lunches and other gatherings, such as the periodic pow-wows with former Fort Worth Mayor Bob Bolen and a group they call “The Speaker’s Table,” where they discuss the world’s problems, even if they don’t always come up with answers. Other hours go to writing a column for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram or just spending time with his wife, Betty, and children and grandchildren. Not to say time hasn’t taken a toll on this go-getter. Nowadays, the inquisitive brown eyes have trouble seeing clearly. Wright stepped into an elevator recently and had difficulty finding the second-floor button, came close to punching the red alarm button, and even pressed down on a keyhole at one point. “My glasses need glasses,” he said.

Other calls come from current politicians, such as Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief, tapping into the connections and expertise Wright gleaned over 34 years in Congress. Then there are the lunches and other gatherings, such as the periodic pow-wows with former Fort Worth Mayor Bob Bolen and a group they call “The Speaker’s Table,” where they discuss the world’s problems, even if they don’t always come up with answers. Other hours go to writing a column for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram or just spending time with his wife, Betty, and children and grandchildren. Not to say time hasn’t taken a toll on this go-getter. Nowadays, the inquisitive brown eyes have trouble seeing clearly. Wright stepped into an elevator recently and had difficulty finding the second-floor button, came close to punching the red alarm button, and even pressed down on a keyhole at one point. “My glasses need glasses,” he said.

An ailment called ischemia makes him dizzy at times. The body is no longer straight and strapping like in those days when the tough, red-headed Texan with an Irish temper was a Golden Gloves boxer and a B-24 bombardier with a Distinguished Flying Cross. The orator’s voice that rang with authority over meetings attended by world leaders is now ravaged by surgeries and radiation treatments for mouth cancer. His mind, however, remains sharp. The lion might be in winter, but he’s not ready for sleep — he’s not even yawning. He remains passionate about affordable healthcare and the environment, and he attends grip-and-grins when political candidates such as Hillary Clinton or John Edwards come to Texas. This fall, he’ll teach at Texas Christian University for the 17th year in a row, reach the ripe old age of 85, and continue showering his dwindling time and energy on his favorite city. “I don’t want to be idle,” he said. “I want to get up every morning and look forward to having something to do.”

An editorial cartoon hanging among memorabilia at the TCU library pays homage to one of Fort Worth’s most celebrated residents. Wright was a caricaturist’s dream. “They always draw me with bushy eyebrows,” he said, laughing. “I don’t know why they do that.” Despite fading from orange to white over the past 84 years, those trademark eyebrows are no less flamboyant. And they still serve a good purpose. “They shade my eyes,” Wright joked. The most telling part of the cartoon isn’t the eyebrows, though. It’s the punch line, which refers to the good fortune Fort Worth enjoyed because of Wright’s influence on Capitol Hill. A tough, ambitious — some say power-hungry — congressman for 34 years, he reached the pinnacle of that governmental body in 1987, presiding over the historic 100th Congress as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. The cartoon, drawn that same year, shows two men talking while a bulldozer breaks ground for the new currency plant. One fellow says to the next, “Jim Wright brings so much money to Fort Worth, the currency printing plant thought it would be easier to just open a branch here.”

An editorial cartoon hanging among memorabilia at the TCU library pays homage to one of Fort Worth’s most celebrated residents. Wright was a caricaturist’s dream. “They always draw me with bushy eyebrows,” he said, laughing. “I don’t know why they do that.” Despite fading from orange to white over the past 84 years, those trademark eyebrows are no less flamboyant. And they still serve a good purpose. “They shade my eyes,” Wright joked. The most telling part of the cartoon isn’t the eyebrows, though. It’s the punch line, which refers to the good fortune Fort Worth enjoyed because of Wright’s influence on Capitol Hill. A tough, ambitious — some say power-hungry — congressman for 34 years, he reached the pinnacle of that governmental body in 1987, presiding over the historic 100th Congress as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. The cartoon, drawn that same year, shows two men talking while a bulldozer breaks ground for the new currency plant. One fellow says to the next, “Jim Wright brings so much money to Fort Worth, the currency printing plant thought it would be easier to just open a branch here.”

It’s no wonder Wright was portrayed as such a Cowtown cheerleader. Through the years, as congressman, majority leader, and speaker, his efforts provided jobs at General Dynamics and other local defense companies and federal support for projects like Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, the Trinity Railway Express, renovation of Main Street and the Stockyards, flood control and creek beautification, and on and on. Forty years ago, Wright’s political finesse ensured a 14-story federal building pegged for construction in Dallas was instead built in Fort Worth. His early appointment to the Public Works Committee, which doled out money for public buildings, dams, and highways, helped him swing numerous projects for Cowtown over the years. His name is attached to Northwest Loop 820, which he helped complete by writing language into the federal Highway Act. His name also lives on in the contentious Wright Amendment, a federal law still being debated 30 years later.

The lifelong Democrat’s impact on his hometown has been so immense that local Republicans have trouble knocking him, unless by complaining that he did too much. “He certainly was adept at bringing home the congressional pork, if you will,” said Tarrant County Republican Party Chairwoman Stephanie Klick. “If it’s a program or project that people want, and it’s good for the local economy and community, that can be good, but it can also be bad. We can agree or disagree as to some of the projects he brought to Fort Worth and whether they were good or excessive spending.” If politicians are measured by their ability to shower attention on their home districts, few can surpass Wright’s legacy. Naturally, he has a stock answer for critics who argue that he was delivering surplus bacon. “One man’s pork is another man’s bread and butter,” Wright said.

That can-do reputation put a target on his back. Partisan accusations of ethical misconduct prompted Wright’s resignation, not in disgrace but certainly in disdain. He bowed out on May 31, 1989, saying, “I am not a bitter man. I am not going to be.”

These days, the man who stood third in line to the presidency likes to stay involved, although now his schedule is busy by design more than necessity. To that end, he and Bolen meet periodically. They make a list of issues, pick a date and place, and invite four additional guests. “We learned that if you get more than six people at a table, they tend to break up into two different conversations,” Bolen said. The get-togethers are private, off-the-record exchanges, which may or may not lead anywhere. “It’s kind of social more than anything,” Bolen said. “We just talk and try to educate ourselves.” Social interaction inspires Wright. His most recent book, The Flying Circus, published in 2005, was prompted by a grandson’s questions about his World War II experiences.

When Bolen stopped in at Wright’s office recently, it was obvious the two old politicians enjoy spending time together. Their next topic is a new process for saving gasoline and reducing emissions. A Dallas group is attempting to adapt hydrogen generators for use in automobiles, and Wright is interested. “It looks like it saves a little over 10 percent on gasoline, and there’s a 38 percent elimination of carbon dioxide and those things that produce global warming and pollution,” he said.

America’s sluggishness in switching to cleaner-running, more fuel-efficient vehicles irritates Wright. If there is a better way, he wants to know. He’ll pass along the information to whomever is in a position to do something. Retiring from politics doesn’t mean he quit caring. On healthcare, for instance, he said, “It is long past time we should have developed some system to guarantee every American access to affordable healthcare. That’s been stalled longer than it should be.”

As for war in Iraq: “We’ve seen an increase in terrorism as a result of our occupying an Islamic and Arab nation. This has created more hostility toward us and more terrorists than all those we have slain and has miscast the United States in an unfamiliar role — the role of an aggressor. As a consequence we’ve lost friends in much of the Islamic and Arab world, and it’s difficult to see what we gained.” Those thick eyebrows furl when Wright gets down to serious matters. Before long, however, he’ll spot an opportunity for a funny remark and ease the tension. And that can lead to any number of anecdotes from a lifetime in politics. Bolen has heard many of the stories, but doesn’t mind hearing them again. One of his favorites goes back to Wright’s days as Weatherford mayor in the early 1950s.

As for war in Iraq: “We’ve seen an increase in terrorism as a result of our occupying an Islamic and Arab nation. This has created more hostility toward us and more terrorists than all those we have slain and has miscast the United States in an unfamiliar role — the role of an aggressor. As a consequence we’ve lost friends in much of the Islamic and Arab world, and it’s difficult to see what we gained.” Those thick eyebrows furl when Wright gets down to serious matters. Before long, however, he’ll spot an opportunity for a funny remark and ease the tension. And that can lead to any number of anecdotes from a lifetime in politics. Bolen has heard many of the stories, but doesn’t mind hearing them again. One of his favorites goes back to Wright’s days as Weatherford mayor in the early 1950s.

Wright was a mere 24 years old when he won his first election to the Texas House of Representatives, serving from 1947 to 1949. Afterward, he moved to Weatherford, worked with his father in a marketing business, and was elected mayor. He’d spend half of the day at his marketing job, the latter half on mayoral duties. But answering phone calls from constituents was a full-time job. The boozers tended to get ideas late at night after a few rounds and go fumbling for a phone, while older folks called early in the morning. One morning, a woman complained about boys with BB guns shooting songbirds in her yard. Another woman called to complain about the grackles roosting in her trees. Wright went to the first woman’s house, picked up the boys with their guns, and drove them to the other woman’s house. Solving two separate problems with one simple act was a model of political efficiency and might stand as the zenith of his career, Wright joked.

Bolen rolled with laughter. Having been a mayor himself, he understands how hard it is to please everyone. “Of course, if you did something like that these days you’d have about four different groups after you,” he said. The story reveals much about Wright’s country-boy roots and problem-solving ways. Another tale, revealing his temper, involves a clash with Amon Carter, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram publisher and about as close to a king as Cowtown’s ever had. After four years as Weatherford mayor, the 31-year-old Wright was ready to make a run at Congress. In 1954 he announced he would run against Carter’s chosen candidate, Wingate Lucas. Just before the election, the newspaper endorsed Lucas and denounced Wright in a front-page editorial. An angry Wright fired off a rebuttal, dug into his personal savings account, and paid $974.40 for an ad that took up most of a page. “An Open Letter to Mr. Amon G. Carter and Fort Worth Star-Telegram” blared the headline. (Later, Wright was told how a copy editor went to Carter and asked whether the paper should print the ad. Carter, according to Wright’s eyewitness, asked if Wright’s check was good. When told it was, Carter responded, “Run it!”)

Wright’s letter, written in the heat of passion, blasted Carter and the newspaper for ignoring his campaign while steering voters toward Lucas: “You have at last met a man, Mr. Carter, who is not afraid of you … who will not bow his knee to you … and come running like a simpering pup at your beck and call.” His skill with words isn’t confined to oratory; the former journalist knows a thing or two about penning columns, books, and angry letters to newspapers. “Is this how you have controlled Fort Worth so long?” Wright wrote back then. “By printing only that which you wanted people to read?” Playing David to the powerful Carter’s Goliath allowed Wright to sling a decisive stone. The letter was the talk of the town, and Wright won the election with 60 percent of the vote. But that was more than 50 years ago. Carter is long since dead. The stories live on, however, at the TCU library, which maintains Wright’s archives of more than a million documents.

Wright’s letter, written in the heat of passion, blasted Carter and the newspaper for ignoring his campaign while steering voters toward Lucas: “You have at last met a man, Mr. Carter, who is not afraid of you … who will not bow his knee to you … and come running like a simpering pup at your beck and call.” His skill with words isn’t confined to oratory; the former journalist knows a thing or two about penning columns, books, and angry letters to newspapers. “Is this how you have controlled Fort Worth so long?” Wright wrote back then. “By printing only that which you wanted people to read?” Playing David to the powerful Carter’s Goliath allowed Wright to sling a decisive stone. The letter was the talk of the town, and Wright won the election with 60 percent of the vote. But that was more than 50 years ago. Carter is long since dead. The stories live on, however, at the TCU library, which maintains Wright’s archives of more than a million documents.

For many folks, Wright remains Fort Worth’s go-to guy. Ancient constituents still call asking for help expediting a passport, bringing soldiers home from the military to tend to a family crisis, or dealing with any number of grackles-in-trees-type situations. “They are friends and people I used to serve, and I feel an obligation to try to get them some help,” he said. “I do these things for the community because I enjoy it.” That same community has been debating the Wright Amendment ever since it was passed in 1979 to restrict flights out of Love Field after Fort Worth and Dallas combined efforts to build an international airport. Last year, efforts to repeal the amendment — a solution agreed upon by local leaders — stalled in a Washington committee led by Vermont Sen. Patrick Leahy, who was concerned about antitrust issues. Moncrief recalled that Leahy and Wright once served in Congress together, and he sought Wright’s intervention. Wright was happy to help — even though it meant repealing a namesake law. “I called Pat and told him what I could, and everything worked out fine,” he said.

Marshall L. Lynam dropped a journalism career — he worked at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Fort Worth Press in the 1950s — to follow Wright into Washington, D.C.’s political trenches. For 27 years, Lynam worked side by side with the congressman and grew to love him like family. He wrote of those years in the insightful and funny Stories I Never Told the Speaker: The Chaotic Adventures of a Capitol Hill Aide, characterizing Wright as a hard-working and clever politician devoted to his constituents back home. Blessed with a golden tongue and easy sense of humor, Wright became one of Washington’s most sought-after campaign stumpers. Former President Lyndon Baines Johnson once suggested that Wright address a Democratic candidate’s rally, describing him as “an eloquent, forceful speaker.” Wright was eager to oblige. If he helped other candidates raise money and get elected, he could depend on them for political support on down the line. Lynam, who now lives in Fort Worth, recalled how Wright once agreed to attend a 1964 fund-raiser for a Mineral Wells politician. Back then, Wright was a three-pack-a-day smoker, but he’d run out of Winstons on this trip. By evening, he was having a nicotine fit.

Marshall L. Lynam dropped a journalism career — he worked at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Fort Worth Press in the 1950s — to follow Wright into Washington, D.C.’s political trenches. For 27 years, Lynam worked side by side with the congressman and grew to love him like family. He wrote of those years in the insightful and funny Stories I Never Told the Speaker: The Chaotic Adventures of a Capitol Hill Aide, characterizing Wright as a hard-working and clever politician devoted to his constituents back home. Blessed with a golden tongue and easy sense of humor, Wright became one of Washington’s most sought-after campaign stumpers. Former President Lyndon Baines Johnson once suggested that Wright address a Democratic candidate’s rally, describing him as “an eloquent, forceful speaker.” Wright was eager to oblige. If he helped other candidates raise money and get elected, he could depend on them for political support on down the line. Lynam, who now lives in Fort Worth, recalled how Wright once agreed to attend a 1964 fund-raiser for a Mineral Wells politician. Back then, Wright was a three-pack-a-day smoker, but he’d run out of Winstons on this trip. By evening, he was having a nicotine fit.

Coincidentally, a new company had recently opened in the little city and was offering an alternative to tobacco — lettuce cigarettes. Company representatives handed out cartons of the new product at the rally, and a grateful Wright, seated on a dais in front of 500 people, eagerly fished one out. With the crowd watching intently, his first drag sent him into a long coughing spell, hardly an advertisement for the innovative local product. He was still getting over that painful attack when his turn at the podium arrived. Lynam recalled how Wright sheepishly admitted that it might take folks a while to get used to lettuce cigarettes. “But I’ll tell you one thing,” he said. “I’d rather smoke a lettuce cigarette than eat a tobacco salad.” Lynam and Wright still get together every other Wednesday for lunch. “You could describe Jim as the type of man you’d like to have as a brother,” he said. Some Republicans more likely viewed him as an agitating brother-in-law with a big mouth and bigger ambition. Before he found himself mired in a 1988 ethics investigation, his ambition was already leading to his undoing. Critics say he rubbed people the wrong way by flouting House rules, stepping on his colleagues’ toes, and trying to control foreign policy, something typically handled by the executive branch. “The blunt instrument of raw power was his tool, and he wielded it with such abandon that for the House to stand, Jim Wright had to fall,” Wick Allison wrote in the conservative National Review in 1989.

For two years, Republicans, led by U.S. Rep. Newt Gingrich of Georgia, accused Wright of various infractions, including using bulk book sales to skirt House rules limiting the amount of speaking fees he could collect. Wright denied the accusations but said little publicly. Republicans smelled blood, and Democrats backed away from the froth. Ethics complaints cut to the core of Wright, a child of the Depression hailing from a family with a strong work ethic and a firm sense of right and wrong. Members of Congress are showered with offers big and small, from a free drink at the corner bar to gratis use of yachts, planes, and condos. Few if any of them completely resist perks of the office. Wright was in that heady zone for many years, but he said his conscience is clean. His main purpose, he said, was to be a successful legislator and vote in a manner that was best for his district, the country, or the world. What some politicians see as right and just, others blast as wrong-headed.

For two years, Republicans, led by U.S. Rep. Newt Gingrich of Georgia, accused Wright of various infractions, including using bulk book sales to skirt House rules limiting the amount of speaking fees he could collect. Wright denied the accusations but said little publicly. Republicans smelled blood, and Democrats backed away from the froth. Ethics complaints cut to the core of Wright, a child of the Depression hailing from a family with a strong work ethic and a firm sense of right and wrong. Members of Congress are showered with offers big and small, from a free drink at the corner bar to gratis use of yachts, planes, and condos. Few if any of them completely resist perks of the office. Wright was in that heady zone for many years, but he said his conscience is clean. His main purpose, he said, was to be a successful legislator and vote in a manner that was best for his district, the country, or the world. What some politicians see as right and just, others blast as wrong-headed.

Wright favored the Franklin D. Roosevelt philosophy of government having final responsibility for the welfare of its citizens. Wealthy businessman and former Texas Rangers baseball team owner Eddie Chiles once dubbed Wright a socialist, midway between capitalist and communist. Chiles disliked governmental interference and said so often on conservative radio spots (his tagline was “I’m Eddie Chiles, and I’m mad!”). Determined to oust Wright from Congress, Chiles vowed to spend buckets of money on Republican candidate Jim Bradshaw’s 1980 campaign. Bradshaw was willing to take on the incumbent despite Wright’s popularity. “I felt we needed a more conservative voice representing this area, and I felt I could perhaps represent the people better than he could,” Bradshaw recalled recently. “Of course [Wright] didn’t agree, and he ultimately won. Jim represented the district well for many years — not that I agree with everything he did.”

Bradshaw is a political consultant and, until recently, was a Republican precinct chairman. He’s also Wright’s neighbor now, and though their political ideologies don’t always match, Bradshaw considers him a friend. “We live a few houses from each other and we take walks together and visit,” Bradshaw said. “He’s a very interesting person who is very much alive and active, and his mind is sharp as a tack. He’s a good man.” Novelist and playwright Larry L. King (The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas) worked as a congressional aide before becoming a fulltime writer, including a two-year stint with Wright. Both King and Wright could be mercurial, and their working relationship was strained at times. King wasn’t used to having such a hands-on boss. “One time we got in an argument about something, and Jim said, ‘I don’t remember the people of Tarrant County electing you to a damn thing.'” King recalled. “Jim threw himself into his job so much that he didn’t leave himself time for anything else. I know he came to rue that later, thinking he should have spent more time with his colleagues and his family, but he was really into the job and really ambitious. Nothing much existed for Jim at that time other than his job and his duties, and he did a hell of a lot for Fort Worth.”

Gingrich’s attack on his ethics hurt Wright more than anyone knew, King said. But the usually astute Wright decided against justifying the accusations with a response. King, who had left Wright’s camp by that time, called his former boss and urged Wright to go on the defensive, to no avail. “It was an amazing bit of PR work, the dark side of PR,” King said of Gingrich’s attack. “Newt took this one little story [about book sales] and peddled it to newsmen all over the country, and it got to be a lot bigger deal than it ever was. Then the grand irony was — I don’t remember how much money Jim got from that book, but it wasn’t much — Gingrich was caught for the same thing, but it was [much more].” Looking back, Wright acknowledged that King was right. If he had nipped Gingrich’s complaints in the bud, they might never have blossomed into full-scale media frenzy. Wright was never officially accused of breaking any laws, but was nonetheless portrayed as a scandalous sneak by top Republicans, including then-Congressman Dick Cheney, whose closet is crammed with Halliburton-sized ethical problems.

“I saw there wasn’t any way I was going to pacify those people,” Wright said. “It was dividing the House in such a way it was making it hard for us to accomplish anything.” Wright urged both political parties to end “this mindless cannibalism,” encouraging a spirit of decorum, where legislators could disagree without being disagreeable regardless. Again, he had misread the writing on the wall. Democrats and Republicans have been at odds since the parties were established, but Gingrich’s attacks ushered in a new era of much more bitter partisanship in Congress that continues in the post-Tom DeLay era. In summer of 1989, Wright resigned, saying his effectiveness as House leader was crippled. His attackers relied on a special counsel paid for by taxpayers. Wright footed his own legal bills, and when the tab hit $700,000 with no end in sight, he decided it was time to quit.

Carlos Moore, a political consultant for Wright, described the ambush as a severe loss, both nationally and locally. “It was a terrible thing to happen to Tarrant County,” he said. “He has not been replaced. They’ve got people trying to fill his shoes, but all they’ve done is built themselves some townhouses downtown and got their sons on government payroll and those kinds of things. I look forward to the day when somebody, if there is such a person of his caliber, comes along and fills Jim’s place.” Critics who described Wright as power- hungry and single-minded “don’t know Jim Wright, and they don’t know much about history,” Moore said. “If you don’t have somebody who is a good strong leader who knows what he’s doing, you can see what happens. The country right now is leaderless.” Gingrich would later resign his own position as House speaker in similar circumstances. But that was long ago, and Wright doesn’t dwell on the bad times. He prefers the one-liners and funny stories. His wit, recall, and experiences under eight presidential administrations make him a sought-after speaker, even today after surgeries have caused him to sound like a man who’s had a stroke.

His long, storied political career finally done, Wright moved back home to Fort Worth and became a professor emeritus at TCU. And then the cancers came in the 1990s, taking up much of his time as he battled to survive, although he still found time to write columns and books and to teach his classes. Turns out, leaving Washington probably saved him. The small lump he found at the base of his tongue in 1991 would have surely gone ignored during his busy House days, he said. Back home, he immediately visited a doctor who diagnosed the problem. Adam Klick was a TCU senior in 2005 when he called his mother, local Republican Party leader Stephanie Klick, to ask whether he should take Wright’s political science class, “Congress and the Presidents.” Klick’s mother encouraged him, and he’s happy he signed up. Wright’s speech was often difficult to understand, but Klick and his classmates focused on every word, he recalled. “It was a semester inside the mind of a political insider,” Klick said. “A lot of things came out of his mouth that you’re not going to find anywhere printed in a textbook.”

His material is largely anecdotal, and Wright draws from a deep well of memories, such as being one of the last people to have a conversation with John F. Kennedy before the president was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. Kennedy had spoken in Fort Worth earlier in the day, even referring to Cowtown as “Jim Wright City.” On the short airplane flight from Fort Worth to Dallas, Wright was explaining to a curious Kennedy how the two Texas cities could be so close in proximity and yet so divergent in personalities. The plane landed, and Kennedy said, “We’ll finish this conversation on the way to Austin.” Wright was riding several cars behind Kennedy when gunshots rang out, and he wondered if a car had backfired or maybe somebody had fired celebratory shots into the air. But as the motorcade continued and Kennedy’s car sped off down Elm Street, it quickly became clear what had happened. “As we passed the crowd, I saw these looks of horror on people’s faces, and I knew they had seen something terrible,” he said.

His material is largely anecdotal, and Wright draws from a deep well of memories, such as being one of the last people to have a conversation with John F. Kennedy before the president was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. Kennedy had spoken in Fort Worth earlier in the day, even referring to Cowtown as “Jim Wright City.” On the short airplane flight from Fort Worth to Dallas, Wright was explaining to a curious Kennedy how the two Texas cities could be so close in proximity and yet so divergent in personalities. The plane landed, and Kennedy said, “We’ll finish this conversation on the way to Austin.” Wright was riding several cars behind Kennedy when gunshots rang out, and he wondered if a car had backfired or maybe somebody had fired celebratory shots into the air. But as the motorcade continued and Kennedy’s car sped off down Elm Street, it quickly became clear what had happened. “As we passed the crowd, I saw these looks of horror on people’s faces, and I knew they had seen something terrible,” he said.

Wright isn’t big on conspiracy theories of multiple shooters. “I could tell all three shots came from the same rifle,” he said.

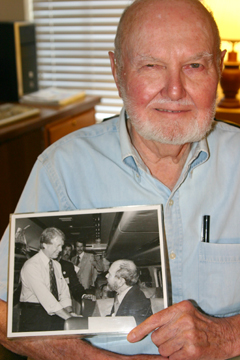

A battered first-edition copy of Kennedy’s 1958 Profiles in Courage sits on a bookshelf next to Wright’s work desk (the book’s original price — $3.50 — is still marked on the jacket’s inside flap). He pulled it off the shelf the other day and handed it to a visitor. The first page contains a personalized inDELETEion from Kennedy: “To Congressman Jim Wright, a public servant of courage with a great future before him.” Wright worked with every president from Dwight D. Eisenhower to the first George Bush and shares what he learned in those days, both pertinent and off-the-wall, with his students. Critics might have painted him as power-mad, but Wright never angled to be president. Moore said he tried many times to convince Wright to seek the top spot. “Some people would rather be over in Congress; they think you’re closer to the people over there,” Moore said. “He knew what the people wanted and knew how to communicate with them, but that’s why he should have been president.”

Actually, Wright admits to harboring presidential aspirations in his youth, before he went to Congress. Once there, he realized the House was where he belonged, and the speaker’s office was his ultimate goal. Getting burned in that role made him realize how hot the presidential seat would have been. “I’m not sure I have the temperament it would have required, the ability to endure a lot of criticism and misrepresentation of something I said or wanted to do, or having my motives misconstrued,” he said. Watching Washington with a critical eye since then, Wright said he’s seen plenty of good things happen for the United States — the long, unbroken period of economic growth in the 1990s, the dozen years of peace between the first Gulf War and the Iraq invasion, and the reduction of the national debt in the late 1990s. Overall, however, the past 20 years haven’t been kind to the country, he said. Jobs are moving overseas, the national debt is again soaring, and the separation between rich and poor is growing wider.

“CEOs have retired with golden parachutes in the multimillions while the laboring families in America have continued to decline in wages,” he said. “I see a vast decline in their well-being and standard of living.” Sometimes, Wright’s classroom lectures veer from political perils to personal passions, and he encourages them to avoid tobacco, using himself as an example. In 1978, Wright noticed he was having trouble with his vocal cords, making it difficult to speak at the many functions he attended. His doctor told him he would have to either quit smoking or quit talking so much. Wright mulled over the diagnosis while driving home. “I reached in my pocket and pulled out my cigarettes and threw them out the car window,” he said He quit cold turkey, but 13 years later he was diagnosed with cancer, which re-appeared in 1998. Radiation treatments left one side of his face unable to grow whiskers, to this day. Naturally, Wright seizes the chance for a joke. “Maybe if I live long enough, I can save enough money on razors to pay for my surgery,” he said.

His face was slightly contorted after doctors grafted part of a femur to his jawbone. Some men might have hidden from public view. Not Wright. He threw himself into teaching. “It makes it a little difficult for me to enunciate some sounds,” he said. “But it doesn’t make me feel crippled, and I’m not going to let it handicap me and stop me from being a social and communicative person.” Each year he figures is his last to teach, but then a new school year rolls around and he answers the bell. For 16 years, that has helped keep him going.”The campus starts bustling with young life,” he said, “and I think, ‘I’ll do it one more year.'”

Nice piece ! I was fascinated by the details , Does anyone know if I could possibly grab a template Copyright PTOL-85 Part B form to work with ?