Representational but with all of the chutzpah of the most offensive installation art, Mueck’s pieces amaze, indulge, and, best of all, rawk. His “Untitled (Seated Woman)” is part of the Modern’s permanent collection and other than “Vortex” — Richard Serra’s massive, outdoor, rusty Twizzler — is probably the museum’s most popular piece. Read my lips: The Mueck exhibit will be the most lucrative and critically acclaimed in the Modern’s storied history. For the show’s success, Mueck and the Modern have only to thank his brazen, singular genius — and the political, social, and economic turmoil of the past 25 years.

Representational but with all of the chutzpah of the most offensive installation art, Mueck’s pieces amaze, indulge, and, best of all, rawk. His “Untitled (Seated Woman)” is part of the Modern’s permanent collection and other than “Vortex” — Richard Serra’s massive, outdoor, rusty Twizzler — is probably the museum’s most popular piece. Read my lips: The Mueck exhibit will be the most lucrative and critically acclaimed in the Modern’s storied history. For the show’s success, Mueck and the Modern have only to thank his brazen, singular genius — and the political, social, and economic turmoil of the past 25 years.

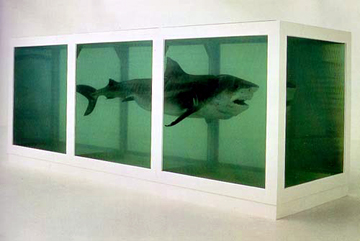

In 1992, the Saatchi Gallery in North London mounted Young British Artists, a show devoted to the ad hoc group of the same name and co-curated by the gallery’s owner, Charles Saatchi, the advertising mogul who also, conveniently, owned most of the work on display. Among the exhibit’s dozens of divertissements, one piece triggered the kind of breathless, epic theorizing normally reserved for uppity white whales. A large, dead shark in a vitrine of formaldehyde, Damien Hirst’s “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” was either a harmless publicity stunt or sign of the apocalypse, depending on whose teeth were doing the gnashing. We may never really know the artwork’s true significance, but we can say without a doubt that Hirst’s glorious, glorified hunting trophy had an impact. It emphatically dotted the “?” to the question that Warhol posited from atop a Brillo box 40 years earlier: What next?

Purely conceptual art like the YBA’s once generated the kind of fevered press and foot traffic that will pursue Mueck at the Modern. But no longer. The style at its most raw and shocking has been largely forgotten. Even now, on the 25th anniversary of Young British Artists, purely conceptual art is still regarded as one long, condescending harangue in an alien tongue. You either speak or tolerate the language or, like a lot of collectors, dealers, critics, curators, and viewers, you don’t.

A shame, because “Physical Impossibility” portended a new beginning, for art, artists, and us. Hirst’s 18-foot tiger shark had been reeled in from the sea on commission, and in its black, soulless eyes and oceanic provenance — and quintessentially British stiff upper lip — lay contemporary art’s possible future. Now that artists evidently had nothing left to say but a million ways to say it, Duchamp’s ridiculous dictum had come true. Art was whatever an artist pointed his finger — or dangled some chum — at. Anything could be art, and anyone, with the right connections and appropriate degree of disdain for propriety, could be an artist. The world was our, um, oyster.

Enter: 9/11.

Experimental work, especially Hirst’s shark, the Chapman brothers’ psycho-sexual mannequins, and Vanessa Beecroft’s naked models, now seemed absurd, offensive even, to order, familiarity, and safety. Representational art, accessible and familiar, took over again. John Currin’s medieval grotesqueries, Robert Bechtle’s car porn, Elizabeth Peyton’s skittish, lacerating blow-jobs to celebrities — they now sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars and anchor major exhibitions. The Muecks of the world, who combine accessible, representational form with conceptual art’s ’tude, are, unfortunately, rare beasts. Hirst recently made his Los Angeles debut, and other than the Hollywood grandees who surfaced, nary a toothy predator was in sight. Even Norman Rockwell, that ol’ sock, has gotten in on the action. A couple of years ago, the populist photorealist was the subject of a massive retrospective at the acknowledged cradle of abstract-expressionism and progressive taste, the Guggenheim.

Ah, if only most of us hadn’t given in to the fear! If only we would have allowed some of our conceptual artists to flourish! Imagine: A-R-T, a word once used to denote colorful shapes on canvas (or cave walls), transformed into a rhetorical loophole, like the legal or religious protections that permit marrying several women at once or suing fast-food joints for serving hot coffee. Imagine: scientists’ calling their stem-cell research “art” and being allowed to proceed freely and, perhaps more importantly, in the grimacing face of political zealotry. Imagine: starting a church in the name of “art” to satisfy your insatiable ego and exploit dim movie stars. Imagine: refusing to pay your bills and telling the bank that you’re simply a performance artist working on a piece about modern indentured servitude called “Freeloading My Fat Ass Off.”

Exaggerations, yes, but they underline the fact that with “Physical Impossibility” we may have been on the cusp of a new, albeit minor, age of enlightenment. Say what you want about conceptual art, but it gets people talking, and from a social standpoint, discussion is healthy. As George Walker Bush and his administration have illustrated, too little talk can be deadly. As for purely representational art, it may get people talking, but the discussion is essentially the same now as it was 400 years ago. The hot topics remain: the right and wrong ways to depict our political leaders, children, and spiritual figureheads; when too much nudity is too much; and where to draw the line between gratuitous schlock and truthful shock.

Alas, the shift in perspective, from dismissing representational art as banal and earthbound to lauding it for its modesty, is what may have irrevocably damaged conceptual art. Can anyone recall the last big stink over a non-representational, installation piece or exhibit? (Chris Ofili’s elephant shit doesn’t count. Nor does Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s public art — their freak flags are for another chat entirely.) Even the historically antagonistic Turner Prize is slouching closer toward the center. Long a lightning rod for frothy criticism, the huge British award recently shortlisted — gasp! — an oil-on-canvas painter.

The promise of “Physical Impossibility,” though, wasn’t all man-eating smiles, broadened horizons, and naked models. “Art” will never belong to just anybody. Only artists. So, you may ask, who decides who’s an artist and who isn’t? The short answer: the Establishment. Well, how do I join? The long answer: Nobody knows. The card-carrying collectors, dealers, critics, curators, and artists hold fast to their de facto fraternity and remain wary of interlopers. And in the same way that Establishmentistas united in opposition to Warhol, they joined hands post-9/11 to defy Hirst and his fish: Crotchety typing monkeys launch fatwas in print media, and the administrators of the art world herd the rabble into naturally lit mausoleums hung with mannerist Studio Art 101 assignments and recycled Caravaggios. The Establishmentistas’ goal is to remind us that art requires exceptional mechanical skill and that Hirst’s shark is as ridiculous to them as it is to us. Basically, the message is, “Don’t get any ideas on cutting in on our business, you damn, dirty rubes. You can’t just dump your leftover sushi in a tank and call it ‘art’ anymore. You have to be able to paint, preferably in the high style of Thomas ‘Painter of Light’ Kincaid or that other guy at the mall, the one who does those pretty bluebonnet fields. Yeah, that guy.”

Perhaps the proverbial nail in the coffin was hammered by Saatchi himself. A couple of years ago, the tastemaker told an interviewer, “Painting continues to be the most relevant and vital way that artists choose to communicate.” Not long afterward, the ad-man sold off a large chunk of his YBA collection.

The Mueck exhibit will be great all around: artistically, financially, spiritually, whatever. But we can’t help but wish there were more like it.-Anthony Mariani

Contact Kultur at kultur@fwweekly.com.