“This kicked off my complete interest in Fort Worth printmaking about 15 years ago,” he said, recalling how he saw it for the first time at an estate sale and couldn’t help but buy it. “Once you see something like this, no other kind of print will satisfy you like a high-quality original print.” The fact that Fort Worth artwork is becoming a hot item among collectors on the East Coast is due mostly to Utter and a small group of local artists who took off on an adventurous romp into abstract freakiness about 60 years ago, back when the world wasn’t watching and few knew that such art could exist south of the Red and west of the Sabine. At the time, more cosmopolitan cities such as Dallas were only tiptoeing toward modernism.

“This kicked off my complete interest in Fort Worth printmaking about 15 years ago,” he said, recalling how he saw it for the first time at an estate sale and couldn’t help but buy it. “Once you see something like this, no other kind of print will satisfy you like a high-quality original print.” The fact that Fort Worth artwork is becoming a hot item among collectors on the East Coast is due mostly to Utter and a small group of local artists who took off on an adventurous romp into abstract freakiness about 60 years ago, back when the world wasn’t watching and few knew that such art could exist south of the Red and west of the Sabine. At the time, more cosmopolitan cities such as Dallas were only tiptoeing toward modernism.

It might seem surprising that a collector such as Barker, who owns large and valuable paintings from some of the city’s most noted early artists, can get excited about a small black-and-white print. A print! Who cares about prints? Turns out, a growing number of folks are getting the bug, and Fort Worth’s short but stellar list of mid-20th-century printmakers is garnering attention these days. Early, original, handmade prints by Fort Worth artists are just as scarce as locally done paintings from the same period. Many focus on historic scenes and appeal to people who get excited about seeing how downtown’s skyline has evolved, or what an old building looked like in the 1920s or 1930s when it was under construction, or how Main Street looked with a line of Model T Fords parked alongside its curbs. While not as eye-catching as paintings, they nonetheless appeal to collectors who love art but have limited pocket money. “It made art affordable to working-class people,” said A.C. “Ace” Cook, whose Stockyards ice cream shop The Bull Ring boasts one of the state’s best private collections of early Texas art. “Every good collector has some etchings, and every wannabe collector can afford one.”

Dallas was fertile ground for printmaking, and a celebrated group of artists known as the Dallas Nine were remarkably productive from the 1930s to 1960s. Jerry Bywaters and Alexandre Hogue created a guild called the Lone Star Printmakers in 1938, and they and other artists such as Otis Dozier and Merritt Mauzey cranked out limited runs of original prints and sold them for $5 to $8 at traveling exhibits across the state. Women artists such as Lucile Land Lacy and Coreen Spellman formed their own group, The Printmakers Guild. Many of these prints survive today, and a devoted collector base has driven up prices in recent years. But in Fort Worth, printmakers weren’t nearly as organized; they tended to do things as much for fun and fantasy as for fiscal fitness. Dallas artists favored lithography with its high-quality prints, but there weren’t any of the expensive litho presses in Fort Worth. The artists who later became known as the Fort Worth Circle leaned toward the simpler etchings, since several of them owned their own hand presses. As a result, the prints are relatively small in number, difficult to find, and often groundbreaking in spirit. And not surprisingly, that’s inspiring collectors to hunt them down like eager bloodhounds.

Dallas was fertile ground for printmaking, and a celebrated group of artists known as the Dallas Nine were remarkably productive from the 1930s to 1960s. Jerry Bywaters and Alexandre Hogue created a guild called the Lone Star Printmakers in 1938, and they and other artists such as Otis Dozier and Merritt Mauzey cranked out limited runs of original prints and sold them for $5 to $8 at traveling exhibits across the state. Women artists such as Lucile Land Lacy and Coreen Spellman formed their own group, The Printmakers Guild. Many of these prints survive today, and a devoted collector base has driven up prices in recent years. But in Fort Worth, printmakers weren’t nearly as organized; they tended to do things as much for fun and fantasy as for fiscal fitness. Dallas artists favored lithography with its high-quality prints, but there weren’t any of the expensive litho presses in Fort Worth. The artists who later became known as the Fort Worth Circle leaned toward the simpler etchings, since several of them owned their own hand presses. As a result, the prints are relatively small in number, difficult to find, and often groundbreaking in spirit. And not surprisingly, that’s inspiring collectors to hunt them down like eager bloodhounds.

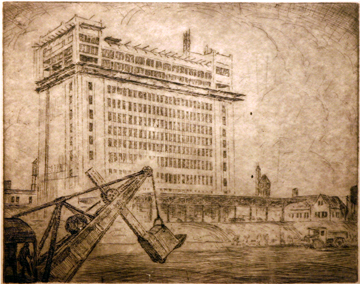

“I can’t think of anything comparable to what was happening in Fort Worth,” said Jane Myers, senior curator of prints and drawings at the Amon Carter Museum. “It was unusual to have progressive artists of their ilk during the 1940s in Texas.” More than two dozen etchings by the early local printmakers will be displayed at the Carter as part of a Fort Worth Circle exhibit early next year. The prints “are among their most important work,” she said. “It’s among the most innovative in terms of style and technique and marks an interesting and important period in Fort Worth art history, this great enthusiasm … when these artists were working together and experimenting without restraint.” The tidy, bespectacled man who arrived by train in 1917 was a rarity in Cowtown. Samuel P. Ziegler, 35, had been well schooled in music and fine arts in Pennsylvania, with an extensive tour of Europe under his belt when he came to teach music at the fledgling Texas Christian University. He would eventually become head of the art department, a post he held for 27 years, and create a dazzling series of etchings featuring the churches, large buildings, street scenes, landscapes, and various construction and demolition projects at a pivotal time in the city’s history. He sketched scenes and then took the drawings home and made prints of them on his small press.

In the art world, “original print” is not an oxymoron. It describes the process of transferring reverse-image sketches onto a plate, applying ink, and then transferring the image onto paper. Prints were generally limited to small runs of 10 to 100 copies, signed and numbered. It was a way to sell art more cheaply during the Depression and the post-World War II years. Old-style printmaking is time-consuming and exacting, and in some ways requires more skill than painting. Taking original paintings or drawings and engraving them in reverse onto flat surfaces made of metal, wood, stone, or any number of materials was a chore. The effort spent on each print and the variables involved when applying the ink made each etching unique. The process is a far cry from photographic and digitalized modern printing methods where thousands or millions of high-quality prints of an image are cranked out with ease. “It might take you a couple of weeks to take a solid copper plate and etch your print in there,” said Greg Dow of Dow Art Galleries. “It was a tedious process. Printmaking was a tough way to try to make any money.”

In the art world, “original print” is not an oxymoron. It describes the process of transferring reverse-image sketches onto a plate, applying ink, and then transferring the image onto paper. Prints were generally limited to small runs of 10 to 100 copies, signed and numbered. It was a way to sell art more cheaply during the Depression and the post-World War II years. Old-style printmaking is time-consuming and exacting, and in some ways requires more skill than painting. Taking original paintings or drawings and engraving them in reverse onto flat surfaces made of metal, wood, stone, or any number of materials was a chore. The effort spent on each print and the variables involved when applying the ink made each etching unique. The process is a far cry from photographic and digitalized modern printing methods where thousands or millions of high-quality prints of an image are cranked out with ease. “It might take you a couple of weeks to take a solid copper plate and etch your print in there,” said Greg Dow of Dow Art Galleries. “It was a tedious process. Printmaking was a tough way to try to make any money.”

Ziegler’s body of work fills spaces in Fort Worth history left empty by photographs and other records. He provided an artist’s eye and sensitivity, and his etchings give the city’s early-20th-century era some personality. Etchings are fragile by nature, and many have been lost or ruined over time. But Ziegler’s descendants still have some of his works, and Barker, a founding member of Collectors of Fort Worth Art, is among his most avid fans. “Mr. Ziegler loved Fort Worth and wanted to record it as he knew it,” Barker said. “Because of him we have images that weren’t recorded anywhere else.” For instance, in 1931 Ziegler made an etching of the new Texas & Pacific train station as it was being built and the old one being torn down. One image depicts the new station rising in the foreground, while the tower of the old station is seen in the distance. “I’ve never seen it anywhere but in this drawing,” Barker said.

Another local artist, Blanche McVeigh, followed Ziegler’s footsteps in the 1930s and eventually surpassed him for sheer number of etchings. She too kept a small press in her house, but later became one of the few people in the country to own one of the new Sturges presses, so heavy and formidable that McVeigh was forced to shore up the floor of her pier-and-beam house to keep it from crashing through. She later built a house with a concrete floor specifically for her press. She willed the 1500-pound behemoth to the Modern Art Museum, and it is still used in workshops. McVeigh’s etchings gravitated toward African-American subjects in later years, and she experimented with aquatinting, which added color but greatly increased the amount of time it took to produce a print. She sold many of her earlier works for $3 each. Later, her prices rose to about $15. “She wouldn’t even have been making 25 cents an hour,” Dow said.

By the autumn of her career, McVeigh was considered one of the top etchers in the state. Yet, like most artists, she couldn’t make a living solely through her craft, and relied on income from her picture framing shop. Eventually, some of her prints featuring African-Americans came to be viewed as almost condescending, after society’s attitudes began to change, and during the 1960s McVeigh reportedly downplayed those works, even refusing to display them in her shop. Today, those prints are most sought after by collectors and can bring $1,000 or more, compared to her earlier architectural renderings that might fetch half that amount. In the mid-1940s, a small group of Fort Worth artists who liked to drink wine, smoke cigarettes, and discuss techniques and theories began gravitating toward an abstract style that was rare among Texas printmakers. Veronica Helfensteller, Kelly Fearing, Dickson Reeder, Flora Blanc, Bill Bomar, Cynthia Brants, and Bror Utter were among the most daring. All were painters of talent but became collectively enthralled with printmaking and challenged one another to see how imaginative and vivid they could get in their work. They trained at some of the world’s best art schools — in New York, Chicago, and abroad — but settled in Fort Worth and stretched the traditional regionalist style to new dimensions.

By the autumn of her career, McVeigh was considered one of the top etchers in the state. Yet, like most artists, she couldn’t make a living solely through her craft, and relied on income from her picture framing shop. Eventually, some of her prints featuring African-Americans came to be viewed as almost condescending, after society’s attitudes began to change, and during the 1960s McVeigh reportedly downplayed those works, even refusing to display them in her shop. Today, those prints are most sought after by collectors and can bring $1,000 or more, compared to her earlier architectural renderings that might fetch half that amount. In the mid-1940s, a small group of Fort Worth artists who liked to drink wine, smoke cigarettes, and discuss techniques and theories began gravitating toward an abstract style that was rare among Texas printmakers. Veronica Helfensteller, Kelly Fearing, Dickson Reeder, Flora Blanc, Bill Bomar, Cynthia Brants, and Bror Utter were among the most daring. All were painters of talent but became collectively enthralled with printmaking and challenged one another to see how imaginative and vivid they could get in their work. They trained at some of the world’s best art schools — in New York, Chicago, and abroad — but settled in Fort Worth and stretched the traditional regionalist style to new dimensions.

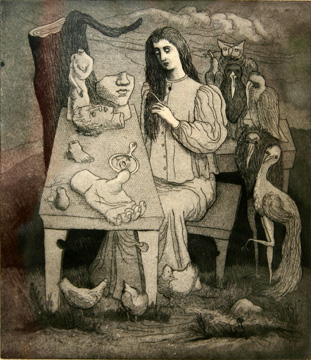

Eventually, they would come to be known as the Fort Worth Circle, and their original etchings are considered by many to be the apex of Fort Worth’s glory days of printmaking. “It takes the right person to appreciate them because they’re not big and colorful,” said local antiques dealer Carter Bowden. “But people who know Fort Worth art like the prints as well as the paintings.” One of the most bewitching of the Circle’s members was Helfensteller, whose good looks and penchant for spooky and absurdist etchings made her stand out even among her collectively sophisticated group of friends. Greg Dow’s father, Don Dow, is 81 and one of the few people left in Fort Worth who knew Helfensteller personally (she later moved to New Mexico and died at 54). Dow was a boy and Helfensteller was in her 20s when she first came to the Dow family gallery to promote her art in the 1930s. “She was very friendly and outgoing,” he said. “She had flashing eyes like a gypsy. She was a nice-looking woman. She was pushy, but a lot of those artists were or they wouldn’t have survived.”

Eventually, they would come to be known as the Fort Worth Circle, and their original etchings are considered by many to be the apex of Fort Worth’s glory days of printmaking. “It takes the right person to appreciate them because they’re not big and colorful,” said local antiques dealer Carter Bowden. “But people who know Fort Worth art like the prints as well as the paintings.” One of the most bewitching of the Circle’s members was Helfensteller, whose good looks and penchant for spooky and absurdist etchings made her stand out even among her collectively sophisticated group of friends. Greg Dow’s father, Don Dow, is 81 and one of the few people left in Fort Worth who knew Helfensteller personally (she later moved to New Mexico and died at 54). Dow was a boy and Helfensteller was in her 20s when she first came to the Dow family gallery to promote her art in the 1930s. “She was very friendly and outgoing,” he said. “She had flashing eyes like a gypsy. She was a nice-looking woman. She was pushy, but a lot of those artists were or they wouldn’t have survived.”

Her work could be strange, which added to her exotic persona. “Her subject matter was macabre, stuff like children in a cemetery flying kites,” Dow said. He described her as odd, “like most artists are.” She asked anywhere from $5 to $15 for her prints, which wasn’t chump change. “Five dollars was a big price — that was a week’s groceries,” Dow said. “Bread was 3 cents a loaf, milk was 12 cents a gallon.” Helfensteller hosted weekly printmaking sessions at her house and allowed the other artists to use her press. They played classical music on the record player, worked into the wee hours, critiqued one another’s work, experimented with new techniques, and spurred themselves to new levels of abstractness. The last survivor of these long-ago meetings, Fearing, recalls them as a magical time in the waning days of a world war, a time of inventiveness and exuberance. Some nights they put aside their experimental engravings and, helped by the sherry they all adored, broke out into impromptu dancing. “We weren’t interested in selling,” said Fearing, now 88 and living in Austin. “We didn’t even exhibit them much. We traded, and we printed enough to have some for ourselves too. We all sold a print or two every now and then. Now they’re collector’s items.”

The godmother of local engraving, McVeigh, sometimes stopped by to pass along pointed advice to these mavericks. “She used to come over to see what we were doing and was rather disapproving,” he said. “She would bring her Southern Comfort with her and sit and make comments.” Another occasional visitor was one of Dallas’ leading engravers, Otis Dozier. “Otis would say, ‘You boys and girls over here have so much fun; we’re so stodgy over in Dallas,’” Fearing recalled. “We weren’t thinking that we would get fame from what we were doing — we were doing prints because we really loved doing them.” There wasn’t a market for their bizarre works, and many remain with the artists’ heirs. Fearing gave his prints to the University of Texas at Austin, where he taught art for 40 years. “In Fort Worth, the best art never comes to auction,” Barker said. “Most of the families that own it are reluctant to let it go.”

The godmother of local engraving, McVeigh, sometimes stopped by to pass along pointed advice to these mavericks. “She used to come over to see what we were doing and was rather disapproving,” he said. “She would bring her Southern Comfort with her and sit and make comments.” Another occasional visitor was one of Dallas’ leading engravers, Otis Dozier. “Otis would say, ‘You boys and girls over here have so much fun; we’re so stodgy over in Dallas,’” Fearing recalled. “We weren’t thinking that we would get fame from what we were doing — we were doing prints because we really loved doing them.” There wasn’t a market for their bizarre works, and many remain with the artists’ heirs. Fearing gave his prints to the University of Texas at Austin, where he taught art for 40 years. “In Fort Worth, the best art never comes to auction,” Barker said. “Most of the families that own it are reluctant to let it go.”

While that type of hoarding makes the items more rare on the open market, it can also hurt their value. For collectors to get excited and create a buzz about an artist, they must be able to find their paintings and prints at auctions and estate sales and then hang them on their walls and talk about them and inspire other collectors to seek out their works. This growing demand then heats up the value. Barker sees that phenomenon slowly playing out now as more people start to appreciate the Fort Worth Circle’s unique place in the state’s early art scene. “With Dallas prints, the increase in value has already taken place,” he said. “In Fort Worth, they will dramatically increase in the next 10 years.” Myers, at the Amon Carter Museum, has already seen an increased interest. “Major print collectors on the East Coast are collecting Fort Worth prints now because there is a greater appreciation for major printmaking of the period, and the quality of the Fort Worth works merit attention,” she said.

While that type of hoarding makes the items more rare on the open market, it can also hurt their value. For collectors to get excited and create a buzz about an artist, they must be able to find their paintings and prints at auctions and estate sales and then hang them on their walls and talk about them and inspire other collectors to seek out their works. This growing demand then heats up the value. Barker sees that phenomenon slowly playing out now as more people start to appreciate the Fort Worth Circle’s unique place in the state’s early art scene. “With Dallas prints, the increase in value has already taken place,” he said. “In Fort Worth, they will dramatically increase in the next 10 years.” Myers, at the Amon Carter Museum, has already seen an increased interest. “Major print collectors on the East Coast are collecting Fort Worth prints now because there is a greater appreciation for major printmaking of the period, and the quality of the Fort Worth works merit attention,” she said.

You can reach Jeff Prince at jeff.prince@fwweekly.com.