Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” The main characters of three movies that open this week would all agree wholeheartedly. They’re all men who try to bend the world to their will, and they don’t have much patience for people who don’t believe in them. Believing in them on film, of course, requires skill on the part of fimmakers and actors. In this trio of movies, that happens only part of the time.

Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” The main characters of three movies that open this week would all agree wholeheartedly. They’re all men who try to bend the world to their will, and they don’t have much patience for people who don’t believe in them. Believing in them on film, of course, requires skill on the part of fimmakers and actors. In this trio of movies, that happens only part of the time.

Amazing Grace is the one historical piece out this week, and it relates the story of a relatively unsung hero. William Wilberforce never became prime minister of Britain throughout five decades in Parliament (1780-1825), but he changed the course of his country’s history through his advocacy of prison reform, education for the poor, and especially his successful efforts to end Britain’s part in the slave trade. The movie arrives at theaters exactly on the 200th anniversary of Wilberforce’s anti-slavery bill was finally passed into law by Parliament, and while the film isn’t bad, you can’t help that both this momentous occasion and this large-spirited man deserved better.

The title comes from the world-renowned soaring hymn of redemption that just happened to be written by Wilberforce’s personal spiritual mentor, the Rev. John Newton, a former slave ship captain who repudiated the trade after finding God. Welsh actor Ioan Gruffudd (pronounce his first name YO-ahn and his last name “Griffith”) plays Wilberforce with the same swashbuckling verve that he shows in the Horatio Hornblower series on British tv, and it fits this firebrand of a character. Steven Knight’s script dramatizes the salient events of Wilberforce’s life: his conversion to Christianity, his friendship with the pragmatic prime minister William Pitt (Benedict Cumberbatch), his education in the slave trade’s inhumanity, his early attempts to ban slavery and their repeated defeats, his nervous breakdown, his recovery and meeting his wife Barbara (Romola Garai), and his ultimate triumph. Some slips in chronology are excusable, though there’s a glaring error when we see Wilberforce working closely with former slave-turned-abolitionist Olaudah Equiano (played by Senegalese music star Youssou N’Dour) — their contact, if any, was severely limited, though Wilberforce probably read Equiano’s autobiography detailing the brutal living conditions on slave ships.

In the end, too much of this movie is taken up by Wilberforce delivering fiery speeches in the face of jeering parliamentary opposition. It’s no surprise that the best sequence here is when he and Pitt deal a crippling blow to the slavers by quietly outmaneuvering them in a near-empty chamber instead of shouting them down. Director Michael Apted (locating a middle ground between the Up series and his bill-paying assignments of churning out Hollywood crap) assembles the story reasonably well and remembers to include a few humorous touches, many of them from Rufus Sewell as hard-drinking abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Even so, all the righteous passion in this film gets to be somewhat exhausting. At the end, you’ll feel like coming up for air.

There’s a fair amount of air in The Astronaut Farmer, undoubtedly the oddest of this week’s movies. Billy Bob Thornton plays Charlie Farmer — geddit? — who walks out of NASA’s astronaut training program after his father’s death and can’t get back in once he’s ready to return. Undaunted by the setback (or by financial problems that are way too easily solved), he starts building his own rocket in the barn on his West Texas farm with the goal of launching himself into space without NASA’s millions or its platoon of technicians and engineers. Instead, his mission command consists mostly of his supportive wife (Virginia Madsen) and adolescent eldest son (Max Thieriot).

This is the fourth film for twin brothers Mark and Michael Polish — their last name is pronounced like the nationality, not like the substance that shines metal. The Polishes are natural successors to David Lynch, sharing his enduring fascination with Middle America and his proclivity for the weird and grotesque, though clearly their resumé lacks anything on the order of Blue Velvet. Their 1999 debut Twin Falls Idaho gave us a taste of their unique sensibility and flair for eye-catching visual compositions, but by the time they got around to their overly precious, obscurantist 2003 opus Northfork, it was clear that they were gazing up their own asses. By contrast, The Astronaut Farmer is their most mainstream effort to date, and clearly they needed to do this project for the sake of their artistic growth.

This is the fourth film for twin brothers Mark and Michael Polish — their last name is pronounced like the nationality, not like the substance that shines metal. The Polishes are natural successors to David Lynch, sharing his enduring fascination with Middle America and his proclivity for the weird and grotesque, though clearly their resumé lacks anything on the order of Blue Velvet. Their 1999 debut Twin Falls Idaho gave us a taste of their unique sensibility and flair for eye-catching visual compositions, but by the time they got around to their overly precious, obscurantist 2003 opus Northfork, it was clear that they were gazing up their own asses. By contrast, The Astronaut Farmer is their most mainstream effort to date, and clearly they needed to do this project for the sake of their artistic growth.

That said, the film is only fitfully persuasive, though even that is something of an accomplishment given the farfetched quality of the plot. The Polishes and their fellow-traveling cinematographer M. David Mullen suffuse all the daytime shots with a golden light that you won’t find anywhere in nature. They make the movie look like it’s set on an alien planet or, if you like, inside a tv commercial advertising a healthy breakfast cereal.

This is the backdrop for Charlie’s many speeches about how a man is nothing if he doesn’t follow his dreams, and this movie would probably be lethal if Charlie weren’t played by Billy Bob Thornton. The star has that air of sangfroid that many Chuck Yeager-influenced test pilots like to cultivate, yet he also infuses the role with a brand of humility that doesn’t come easily to many movie stars. He doesn’t preen or strike heroic poses and comes off as just another guy with a hobby that he’s passionate about. The decency that bubbles to the surface in this beautifully understated performance is the most genuine thing about the film.

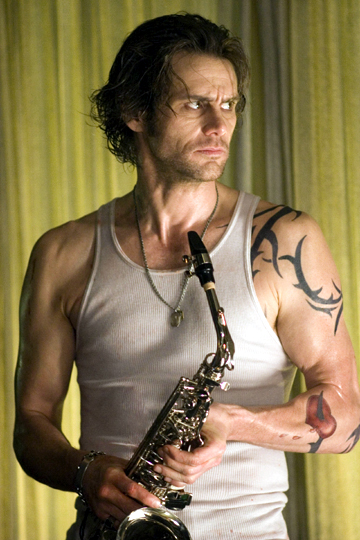

Of course, sometimes a man who fixates on an idea isn’t idealistic, he’s just insane. That’s what happens in The Number 23. Jim Carrey plays Walter Sparrow, a city dogcatcher whose boring, essentially happy life takes an unhappy turn when his wife Agatha (Virginia Madsen again) buys him a self-published, self-printed novel that shares the movie’s title, written by an author with the groan-worthy pen name of “Topsy Kretts.” We see the book’s story play out as Walter reads: A jaded police detective who calls himself Fingerling (also played by Carrey) is drawn into madness after failing to save a suicidal girl (Lynn Collins) who’s obsessed by the number 23. The same obsession soon swallows up both Fingerling and Walter, who cooks the letters and numbers in his name, birthday, driver’s license, and every other aspect of his life so that it comes out to 23. Agatha and his other loved ones try to convince him that he’s seeing patterns where none exist, but when Fingerling starts fantasizing about killing the novel’s femme fatale character (Madsen once more), Walter fears that he’ll do the same thing to Agatha.

When he’s not mucking up Hollywood franchises or literary adaptations, director Joel Schumacher loves to do these moody thrillers with surprise endings (8MM, Flatliners), and first-time screenwriter Fernley Phillips caters to his taste quite well. The plot, when it’s revealed in its entirety, turns out to rely on some jaw-dropping coincidences, but that isn’t the biggest problem. No, the real defect here is that we’ve already seen a better version of this movie. Darren Aronofsky’s 1998 film π is also about a guy with paranoid delusions that revolve around numbers, and it’s weirder, tighter, more convincing, and more harrowing. Schumacher’s movie never comes close to replicating the former’s hallucinatory power.

When he’s not mucking up Hollywood franchises or literary adaptations, director Joel Schumacher loves to do these moody thrillers with surprise endings (8MM, Flatliners), and first-time screenwriter Fernley Phillips caters to his taste quite well. The plot, when it’s revealed in its entirety, turns out to rely on some jaw-dropping coincidences, but that isn’t the biggest problem. No, the real defect here is that we’ve already seen a better version of this movie. Darren Aronofsky’s 1998 film π is also about a guy with paranoid delusions that revolve around numbers, and it’s weirder, tighter, more convincing, and more harrowing. Schumacher’s movie never comes close to replicating the former’s hallucinatory power.

Strangely enough, both π and The Number 23 were shot by the same cinematographer, Matthew Libatique. He contrasts the shadowy look of Walter’s story with the overexposed look of Fingerling’s story, and it’s fairly inventive work. The same could be said for Carrey, who takes his career in a completely logical direction; anyone who’s seen his manic comedic performances won’t be surprised that he can play a crazy dude in a straightforward manner. His emaciated frame and the haunted, psychotic look in his eye would do any dramatic actor proud. Still, neither he nor anyone else in this movie can elevate this material above its essential schlockiness.

One last thing: I can’t believe the filmmakers here missed the chance to work in a Michael Jordan reference. There was another guy possessed of unshakable, single-minded focus. It would have fit the theme of this week’s films all too well.