She is then sent home where she tries to cope with her renal failure until the symptoms — nausea, vomiting, extreme fatigue, confusion, delirium, seizures, and, near the end, coma — become so severe that her daughter takes her back to the ER. Without a weekly dialysis regimen — which would cost about $1,400 a month for an uninsured person — and a doctor monitoring her care, one dialysis provider said, she cannot hope to live much longer.

She is then sent home where she tries to cope with her renal failure until the symptoms — nausea, vomiting, extreme fatigue, confusion, delirium, seizures, and, near the end, coma — become so severe that her daughter takes her back to the ER. Without a weekly dialysis regimen — which would cost about $1,400 a month for an uninsured person — and a doctor monitoring her care, one dialysis provider said, she cannot hope to live much longer.

Rosalita is also in her 40s. She lost a breast to cancer last year after JPS emergency doctors discovered a malignancy. Months later, however, the oncologist’s recommendations for follow-up radiation and chemotherapy treatments — which could cost $10,000 and $16,000 a year respectively — have not been followed. Without such treatment, Rosalita’s cancer may recur. She has no way of knowing if it has because she has not seen a doctor since the surgery.

Maria and Rosalita share a heritage and a dilemma: They are both now poor Tarrant County residents who can’t afford to pay for medical care and can’t receive free medical care at the county hospital’s health clinics because they lack the necessary papers — either a Social Security card or a passport — that prove they are in this country legally. They are among the estimated 98,600 undocumented immigrants in Tarrant County, a large percentage of whom have no access to regular healthcare.

Tarrant is the only urban county in Texas that refuses to provide preventive and follow-up medical care to undocumented immigrants in most situations. The board of JPS, which operates 18 primary-care clinics around the county, cut off those services two years ago, saying that the public hospital system could no longer afford to serve those folks and still carry out its other missions.

The volunteers at Allied Communities of Tarrant don’t buy that argument, and neither do Fort Worth State Rep. Lon Burnam, who calls the policy “draconian,” or Tarrant County Commissioner Roy Brooks. Burnam says he will seek legislation this year to prevent such policies.

Brooks supports ACT’s call for a change in JPS policy. The commissioners court oversees the hospital district, and Brooks appointed a board member two years ago who supports his views. The hospital board only recently decided to do its own study of immigrant care costs. “We will still have to wait on the board to release the findings of its study,” which could take several months, he said.

ACT isn’t waiting, however. On Tuesday, the grassroots activist group released a study that uses the hospital district’s own economic data to show that JPS could serve all of the county’s poor without raising taxes or hurting its healthy bottom line. According to their study, the public hospital has been crying poverty while building up a $329 million surplus in the last eight years. ACT charges that JPS’ claims that it goes in the hole each year to provide charity care don’t hold up. In fact, according to the group’s report, the hospital district last year “made a $17 million profit from charity care while sick people were turned away.”

Since 2004, JPS, under orders from its board of directors, has refused to provide charity care to anyone who cannot prove he or she is a legal U.S. resident. JPS makes exceptions only for the emergency rooms, which by law cannot refuse emergency care to anyone; women seeking prenatal care at JPS maternity clinics, which are supported by a federal grant; students seen at JPS’ seven school-based clinics, which also are prohibited by law from discriminating on the basis of citizenship; and those needing “urgent” (i.e., not quite “emergency”) care.

Robert Earley, senior vice president of the JPS system, said hospital officials can’t say whether ACT is right in its calculations until JPS has had more time to look at the group’s report — and to get the results of its own study. He said pressure from ACT and other groups, on both sides of the issue, did contribute to the hospital initiating that study. Care for undocumented immigrants is an emotional issue, he said, on which few people are neutral: “There are people on one side saying, ‘You better make sure you never provide that care.’”

JPS’ own study will look at the local undocumented population, at JPS’ current capacity, health trends among the immigrant population, and legalities of providing or not providing care — including whether or not a policy of denying care is constitutional. Earley said immigration is an issue that must be addressed at many levels of goverment, not just by JPS.

He said that JPS does not refuse care — but did acknowledge that, when people ask for services that don’t fall under the exceptions, and they can’t provide proof of citizenship, “then it is on a fee-for-services basis, and obviously, if they can’t pay, services won’t be rendered.”

ACT will go to the JPS board in February and ask again — as it has for more than a year — for a change in policy.

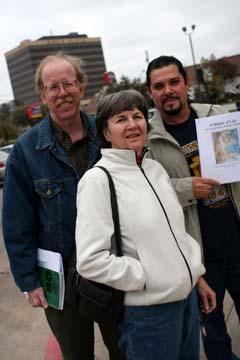

“The situation here [in Tarrant County] is too critical for us to wait,” said ACT member Ann Sutherland, a retired school teacher who also spent 13 years as a senior staff member of the California legislature. “People are sick and dying.” ACT not only wants JPS to provide care for undocumented immigrants, but also to implement a sliding-scale fee program for Tarrant County families without insurance, whose income puts them just over the federal poverty limit.

Because of poverty and JPS’ policy, ACT member José Aguilar said, many immigrants’ primary-care doctor is whoever happens to be on call in any of the area emergency rooms when they get sick or injured.

ACT, a faith-based organization, has been raising quiet hell on poor people’s behalf since the early 1980s, over everything from housing to electrical bills. But JPS may be its biggest challenge yet.

Sutherland, Aguilar, and nursing student David Burlingame — three of the 30 or so volunteers who put together the study — all said that the issue for them was one of morality and human rights. But they knew they had to show that rescinding the policy made economic sense and wouldn’t require a tax increase. “We used JPS’ own data to make our case,” Sutherland said.

In 2006, according to the ACT study, the district’s end-of-the-year surplus was $58 million — a figure that so excited the JPS board that it gave a huge raise and bonus to CEO David Cicero, making him the county’s highest-paid employee. (His compensation package now totals $648,480.) But the district’s “available cash” is the whopper. That column shows $329 million, the accumulation of surpluses the district has piled up since 1998. These surpluses, according to ACT, come from Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance payments for services to paying clients. But they also come “from JPS’ denial of service to the undocumented,” the authors wrote, “because funds allocated to serve charity clients remain unspent. … In effect JPS is making money by not serving the medically indigent.”

ACT asserts that the district “presents its financial information in a manner which implies that it operates charity care at a loss,” but that the figures don’t support that claim. In its 2005 Report to the Community, JPS said that it had gone $62 million in the hole in its charity care fund. It based its numbers on $275 million spent on charity care versus $213 million in local property tax revenue collected. Trouble is, ACT says, JPS failed to report two other important streams of revenue for charity patients during that time. In information obtained via an open records request, ACT found that along with the $213 million in property taxes, the district received an additional $73 million from the Texas Disproportionate Share Revenue fund, federal money passed through to the state’s public hospitals that serve large numbers of uninsured and Medicaid patients. JPS also received $6.3 million from the state Tobacco Fund, the pot of money available for charity healthcare created by the $15 billion settlement of the state’s federal lawsuit against the tobacco industry. When those funds were added, the district actually had a surplus in its charity fund of $17 million, ACT concluded.

ACT looked at the numbers of undocumented immigrants in the county, as estimated by several federal agencies, then compared those numbers with data from Harris and Travis counties, both of which provide care to their undocumented populations and still operate in the black. The group estimated that caring for low-income, undocumented immigrants would cost $2 million to $4.2 million a year. The group has proposed that JPS appropriate $10 million — approximately two percent of its current operating budget — to reinstate care for the undocumented and the working poor who have fallen through the cracks.

ACT also makes the argument that not providing healthcare for such a large chunk of the populace is dangerous for the larger community. Many studies show that failure to provide preventive care and early treatment costs communities much more in the long run, in the spread of infectious diseases, increased costs for emergency room visits, lost productivity, and lost school time for kids. Burlingame, who often works at the health fairs put on by various community groups, pointed out that many of the people screened at the fairs are undocumented workers who are found to have serious conditions such as diabetes and heart disease and infectious diseases such as hepatitis and tuberculosis. “This is very frustrating, because there is no place in this community where we can send them for further diagnosis and follow-up care,” he said.

Brooks said the ACT study is a first major step toward correcting the JPS policy. “What part of contagious do they [the JPS board] not understand?” he asked. Regardless of where one stands on immigration, the board’s decision is simply “bad public policy,” he said. “The public health implications of leaving diseases untreated are enormous.” And then, he said, there is the financial cost. “These folks are left with no choice but to use the local emergency rooms, and that is the most expensive form of healthcare there is. That cost is passed on to all of us.” He said that others may also question whether the JPS policy violates the U.S. Constitution’s pledge of equal protection. “But my concern is public policy … and this one is bad.”

ACT members said that what they’re asking for is modest in light of the financial health of the district. “We call it the two percent solution,” Aguilar said.

Sutherland said the ACT study clearly shows the money is available now to make the change in policy and will continue to be available in the future. “Bringing the undocumented back into the health care system will not hurt the taxpayer or the district’s bottom line,” she said.

ACT members “are very pleased with Rep. Burnam’s support, and we want his bill to pass,” Sutherland said, but added that JPS can change the policy without it.

“The board can do this right now, if it wants to,” she said.