Their dreams of taking back the county were given a big boost in November when Democrat Paula Hightower Pierson, a former Arlington City Council member, defeated State Rep. Toby Goodman, a moderate Republican who held the Arlington-area District 93 seat for eight terms and whose social views and legislative agenda put him more often in the Democratic camp than that of his own party.

Their dreams of taking back the county were given a big boost in November when Democrat Paula Hightower Pierson, a former Arlington City Council member, defeated State Rep. Toby Goodman, a moderate Republican who held the Arlington-area District 93 seat for eight terms and whose social views and legislative agenda put him more often in the Democratic camp than that of his own party.

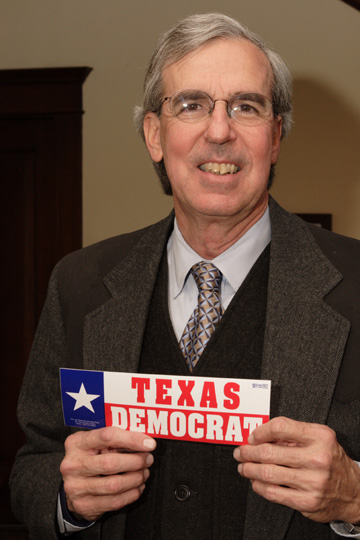

“These were two good, decent candidates, closely aligned in many areas, especially on women and children’s healthcare, education, the environment, and animal rights,” said University of Texas at Arlington political science professor Allan Saxe. In his eyes, the similar political views of the two candidates make the outcome at the ballot box all the more important.

“It was a tough call for the voters in that district. … That’s why Paula’s win is hugely significant for the Democrats,” he said, “because it gives the party a psychological boost. … It’s their first big victory in a long, long time.”

For a party so long on the outs, Pierson’s win against a longtime and popular incumbent has some Democratic stalwarts here almost giddy over the possibility that Tarrant County will go the way of Dallas County in a few more election cycles. There, the Dems won 47 contested races this year — 42 judgeships, plus district attorney, county judge, district clerk, county clerk, and county treasurer — putting that county in Democratic hands for the first time in 20 years. “We could do it as early as 2008,” Tarrant Democratic Party chairman Art Brender said, “or 2010 at the latest. … We are set to take back this county.”

To most observers in a county that former GOP chairman Steve Hollern said turns out more net Republican voters than any place outside California, such a prediction raises only one question: What drugs are they on? This is, after all, only one win in a county where, out of 80 partisan-elected positions from the courthouse to the statehouse plus two congressional offices, only eight offices are now in Democratic hands. The reality is that their first big win in 20 years didn’t advance their political agenda by very much — and they needed the help of a Dallas group to do even that. Can the party really be hanging its hopes on a win in a race when there wasn’t a dime’s worth of difference between the candidates?

Yes, but not as soon as Brender is predicting, said Tarrant County Criminal Court Judge Daryl Coffey. The idea of the Democrats taking back the county in two years or even four is “totally unrealistic,” he said. “There are still too many solid Republican precincts,” he said. Nonetheless, the lifelong Republican believes that a Democratic takeover is probable in about 15 years, due primarily to the fast-growing Hispanic population and the traditional pendulum swing of politics in this country.

And if the Democrats are to be successful, Arlington writer and LULAC activist Richard Gonzales said, the first order of the day must be the Latino voter. To win back the county, the Democrats need to “help Latino candidates get into office. … Too often, the Democrats have asked the Latinos for their support but have not reciprocated. … Time and demographics are on the Latino side. It’s foolish for Anglos to resist the change in who will be calling the political shots in the near future.”

And if the Democrats are to be successful, Arlington writer and LULAC activist Richard Gonzales said, the first order of the day must be the Latino voter. To win back the county, the Democrats need to “help Latino candidates get into office. … Too often, the Democrats have asked the Latinos for their support but have not reciprocated. … Time and demographics are on the Latino side. It’s foolish for Anglos to resist the change in who will be calling the political shots in the near future.”

The Republicans, Gonzales said, will never be the Latinos’ pals. There is now too much bitterness over immigration issues. “Until moderate Repubs take over the party and start reversing English-only proposals, the [border] wall strategy, and enforcement-only legislation, [Republicans] will not succeed in wooing Latinos in large numbers.”

And as for Pierson’s win? “I’m glad that Paula won. However, it would have been sweeter if it had been a Latina Democrat,” he said.

Saxe, however, believes that a takeover by the Dems in Tarrant County in 2008 is not far-fetched. “The demographics of the county are changing more quickly than most people realize, and those changes favor Democrats,” he said.

Don Woodard agrees. The lifelong Democrat who has been a party activist here since the 1950s said, “The [Latino] wave is coming our way … you might as well try and stop the ocean.” The minority vote went to the Democrats in Dallas, he said, and it will do so here. Hispanics now make up 42 percent of the population in Tarrant County, according to the North Central Texas Council of Governments, up five percent since the 2000 census.

Saxe, a political junkie who has taught political science at UTA since 1968 and writes a political column for the Arlington Star-Telegram, and Woodard both remember the bloody battles between Democratic conservatives and liberals in the 1960s before the conservatives left to become Reagan Republicans. And both said that the party has to become tolerant of a wide range of views and let go of its “purist” litmus tests — advice that Republicans got used to hearing (and in many cases rejecting) in past years. Even Pierson was criticized by some in her party for not being “pure enough,” she said, because she reached out to Republicans for support and because she committed the sin of praising a Republican candidate.

The rapid growth of the Hispanic population here is the most obvious factor in the Democrats’ favor, but there is another that’s gone unreported, Brender said — the Alliance airport development in far north Fort Worth. A significant number of the firms that have moved into Alliance in the past decade, he said, are union companies. “There’s been a big jump in union membership in the county, especially in the northern suburbs, and most of that is thanks to Ross [Perot] Jr.’s development. I don’t think that’s what he intended,” Brender added with a laugh, “but it’s gonna help us take back the county.”

Local Republican activists such as Hollern see the handwriting on the wall if their party continues on its present path — that is, the failure to deal with the growing Hispanic population, a lack of leadership in Austin, and, at the national level, the abandonment of the party’s fiscally conservative principles, waves of scandal, and, of course, the two-ton elephant in the living room — the war in Iraq.

While the war, at first blush, didn’t seem to play significantly in most county races here, Goodman puts it at the top of the list of reasons for his defeat, followed by deficit spending, a general disgust with George Bush’s leadership, and the ethically challenged national party.

While the war, at first blush, didn’t seem to play significantly in most county races here, Goodman puts it at the top of the list of reasons for his defeat, followed by deficit spending, a general disgust with George Bush’s leadership, and the ethically challenged national party.

Fort Worth Democratic State Rep. Lon Burnam, however, said Goodman’s defeat can also be laid to an ethical lapse of his own that dominated the campaign in its last month. A complaint filed in September with the Texas Ethics Commission by a Democratic political action group supporting Pierson accused Goodman of improperly using campaign funds to pay rent on a couple of homes owned by his wife in the Austin area. The houses, used by Goodman as his residence when the legislature was in session, were bought by the legislator and then transferred to his wife Gloria. He has paid rent to her of about $1,600 a month since. “It was the sleaze factor that stuck,” said Burnam of Pierson’s upset victory.

But Democrats can’t depend on Republicans to keep shooting themselves in their ethical rump for the next two years. If the party expects to hear donkeys braying across the county by 2008, it’s going to have to follow the blueprint that got Pierson elected, said Saxe. “They have to run younger, energetic candidates who appeal to a broad spectrum, especially Hispanics and youth, and, if the district is manageable, knock on as many voters’ doors as possible. Paula really worked her district; she knocked on about 10,000 doors. … Nothing beats the personal touch.”

Woodard said it’s also going to take “plain old basic precinct-organizing, year ’round. No precinct can be ignored.”

It also takes money, Burnam said. Pierson spent more than $300,000 to win the job. Goodman spent $400,000 to lose it.

Early on, Goodman, an Arlington lawyer, was the odds-on favorite to win. The long, narrow district stretches west from the Dallas County line, running from Mosier Valley’s mostly low-income neighborhood on the north to Mansfield’s high-end new housing developments on the south. In between are some of Arlington’s most solid middle-class and blue-collar neighborhoods. The district votes Republican, but not by large margins.

Still, Goodman had easily won re-election over the years in spite of (or perhaps because of) his reputation as a maverick whose politics seldom followed the party line. He never dodged his pro-choice position, stood solidly behind stem-cell research, acted as an advocate on women’s health issues, and pushed to restore money to the Children’s Health Insurance Program that his party cut to the bone a couple of years ago. He supports tax incentives for alternative energy technologies such as biomass and opposes TXU’s push to build more coal-fired plants upwind of his district. Two years ago he took on one of the most powerful members of his party, U.S. Rep. Joe Barton of Ellis County, when he publicly spoke against Barton’s heels-dug-in opposition to more stringent controls on the cement plants in Midlothian that routinely blow streams of pollution into the Metroplex. “That wasn’t a partisan issue, never was,” Goodman said. “It is a health issue, and my constituents are being hurt badly by the pollution from those plants.” Democrats in the district were more than comfortable with him as their representative in Austin.

He had big-name endorsements, from Democratic Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief to Republican Tarrant County Judge Tom Vandergriff to Arlington Mayor Robert Cluck, and many voters struggled to see the differences between the two candidates.

He had big-name endorsements, from Democratic Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief to Republican Tarrant County Judge Tom Vandergriff to Arlington Mayor Robert Cluck, and many voters struggled to see the differences between the two candidates.

Then Pierson’s supporters found Goodman’s Achilles heel: the allegation that he had used campaign funds improperly to pay for the homes in Austin that produced income for his wife and, thereby, for Goodman himself. Campaign ethics laws forbid lawmakers from using campaign funds to benefit their personal estates. The state ethics panel has since issued a statement urging lawmakers to drop such arrangements but has never ruled on whether the practice is legal, as Goodman contends it is.

The allegation, coming late in the campaign, may have been enough to tip the balance in Pierson’s favor. “Toby is a good man,” Burnam said, “but on this he stumbled badly.”

In 1998 Goodman bought an Austin condo for $123,000 and immediately transferred ownership to his wife. He lived in the condo during legislative sessions and paid yearly rent to her. She sold the condo in 2003, and the couple bought the second house, just outside Travis County, for $209,000. The property, as before, was promptly transferred to Gloria’s name. Again, Toby lived there while the legislature was in session and paid a yearly rent from campaign funds.

Since 1998, he has paid $106,000 to his wife for rent on the houses, according to the Democratic political action group that filed the complaint, Texas Values in Action Coalition. TVAC, founded in 2005 by Dallas Democrats, contributed about $14,000 to the Pierson campaign. It has also been credited with helping elect the 47 Democrats who swept the Republicans out of Dallas County in November.

Goodman called the allegations dirty politics by a candidate “who had no agenda and turned to mudslinging to divert voters’ attention. … The accusation was dead wrong.” He never denied that he lived in the houses owned by his wife during legislative sessions or that he used campaign money to pay the rent. “It was a necessary legislative expense,” he said. “It is allowable by law. And it is perfectly legal.”

He is right that the law allows legislators to use campaign funds to rent temporary housing when they are in Austin doing the people’s business. However, an ethics reform law passed by the then Democratic-controlled statehouse in 1991 — and supported by Goodman — prohibits legislators from using campaign money to buy homes to live in during the session. In 1996, the ethics commission found a loophole in the law that allowed legislators to rent from their spouses as long as the legislator held no interest in the property. Burnam said that Goodman and others have been violating the spirit of the law by buying homes with their own money, transferring ownership to their spouses, and then paying down the mortgage by renting the homes with campaign funds.

He is right that the law allows legislators to use campaign funds to rent temporary housing when they are in Austin doing the people’s business. However, an ethics reform law passed by the then Democratic-controlled statehouse in 1991 — and supported by Goodman — prohibits legislators from using campaign money to buy homes to live in during the session. In 1996, the ethics commission found a loophole in the law that allowed legislators to rent from their spouses as long as the legislator held no interest in the property. Burnam said that Goodman and others have been violating the spirit of the law by buying homes with their own money, transferring ownership to their spouses, and then paying down the mortgage by renting the homes with campaign funds.

“It is a very deliberate effort to circumvent the law,” Burnam said. “And if it’s not technically illegal, it is clearly unethical.” It not only improperly enriches the spouse and, by extension, the legislator, he said, but it also presents a conflict in that the money used to do so was given by lobbyists, political action committees, and others who look to him to further their agendas.

TVAC also leveled similar accusations against four other Texas legislators, including two more from this area, Kim Brimer and Vicki Truett. Both, the group charged, are using campaign money to rent Austin residences owned by their spouses or, as in Brimer’s case, by a company owned by his wife. The legislators have also used campaign money to pay utility bills on those homes. The ethics of those transactions will be front and center in future campaigns here, Burnam said. “This is an issue that resonates when most voters are struggling to pay their mortgages and their electric bills.”

The ethics commission’s statement urging — but not directing — lawmakers to stop the practice came three weeks after the election.

Goodman, however, doesn’t think his alleged ethical problems were a factor in his defeat. While the war, at first blush, didn’t seem to play significantly in most county races here, Goodman says it was in fact the number-one reason for his defeat. “We couldn’t get our people out,” he said. “They showed their disapproval [of the national leadership] by staying home.” And because Goodman has consistently gone against the Republican leadership on hot-button issues such as abortion rights and stem-cell research, he said he got very little support from the county party hierarchy. “But at the end of the day, it didn’t matter.”

“The low [Republican] turnout across the county was the factor that’s been missed by the media here,” GOP activist Hollern said. “For almost a decade, it’s been 72 percent or higher. This year it was in the mid to low 50s, while the Democratic vote remained about the same.” Pierson, for example, got no more votes than Goodman’s opponent did two years ago. “It wasn’t so much a Democratic wave of new voters,” he said, “it was conservatives and moderates sitting this one out.

“Republicans screwed up badly in Austin and D.C. … They walked away from the basic tenets that got them elected in the first place, small government and only spending [the money] we raise,” Hollern said. The national debt is an outrage to conservatives, he said, and the war is becoming as unpopular among moderate Republicans as it is among Democrats for its cost in American lives as well as in dollars. Add to those woes the party’s scandal-of-the-week soap opera, and what you ended up with, he said, was the lowest GOP voter turnout here in years. If the party doesn’t change course, Hollern said, Brender’s 2008 prediction of a county-wide sweep could be on target.

“Republicans screwed up badly in Austin and D.C. … They walked away from the basic tenets that got them elected in the first place, small government and only spending [the money] we raise,” Hollern said. The national debt is an outrage to conservatives, he said, and the war is becoming as unpopular among moderate Republicans as it is among Democrats for its cost in American lives as well as in dollars. Add to those woes the party’s scandal-of-the-week soap opera, and what you ended up with, he said, was the lowest GOP voter turnout here in years. If the party doesn’t change course, Hollern said, Brender’s 2008 prediction of a county-wide sweep could be on target.

Pierson, 56, a real estate agent who spent eight years on the Arlington City Council before resigning to run unsuccessfully for mayor in 1997, had been out of politics for almost 10 years when she was approached about a year ago by local Democratic activists who asked her to run for Goodman’s seat. “At the time, Toby had put out the word that he wasn’t going to run,” Pierson said.

She jumped in gladly, because she thought it would be an open seat and one the Democrats could win, considering that voters for 16 years had sent a man to Austin who is pro-choice and pro-environment and even shared some of Paula’s own ideas about animal rights. Goodman sponsored the legislation that banned cock-fighting in Texas four years ago. He could always be counted on to be the one Republican approachable from the Democratic side of the aisle, Burnam said.

Two years ago, however, signs appeared that suggested Goodman’s popularity was slipping. His Democratic opponent that year was an unknown who campaigned very little and still got 45 percent of the vote. “Shoot, that showed us the seat was winnable with some good, old-fashioned campaigning,” Pierson said, in a Texas drawl that sounded like Ann Richards was on the other end of the phone line. Goodman was an old friend, she said, and if she’d known he was going to run after all, that might have stopped her. “But I was committed by the time he announced, so I stayed in.” The two are not friends any longer, she said. “He won’t return my calls. But I hope that will change. My door’s open to him.”

In fact, Goodman said he plans to spend some time this session lobbying his former colleagues on behalf of energy alternatives such as biomass, an issue that is high on the Democrats’ agenda, again emphasizing the similarities between Goodman and the folks who kicked him out.

Art Brender has no doubt that his party will take back the county, and he plans to use the formula that won in Pierson’s race — if he hangs on as county chairman. Brender faced his most serious challenge in this year’s primary and came out on top. However, one of the biggest criticisms against him was his failure to run candidates for as many offices as he could find warm bodies for, especially the judgeships.

This year, the local party fielded 20 candidates, more than in recent memory, mostly young, many women and minorities. The Democrats ran candidates for county commissioner, district attorney, county clerk, Congress, and the statehouse, but only one, B. C. Cornish, ran for a seat on the bench. Most of the candidates, Brender said, had no chance of winning and knew it, but their presence kept their opponents busy enough that they “didn’t meddle in other races, like Paula’s, where we had a chance of winning.” The party put most of its resources into Pierson’s race and into Terri Moore’s unsuccessful campaign to unseat Tarrant County District Attorney Tim Curry.

Brender said he was pleased with John Morris’ race against U.S. Rep. Kay Granger, even though the Democrat lost. Morris campaigned hard against the popular Granger, “and she had to work for her job,” the county chairman said. Morris “was willing to put himself out there to stop her from intervening in other races.” The party poured its money into phone banks and its volunteers onto the street to knock on doors.

Brender said he was pleased with John Morris’ race against U.S. Rep. Kay Granger, even though the Democrat lost. Morris campaigned hard against the popular Granger, “and she had to work for her job,” the county chairman said. Morris “was willing to put himself out there to stop her from intervening in other races.” The party poured its money into phone banks and its volunteers onto the street to knock on doors.

Brender’s optimism is based in part on the changing demographics of the county and in part on his belief that the candidates the party ran this year are young enough that they will stay involved. “This was an unusual year,” he said. “There was not a strong candidate at the top [in the governor’s race], and Kinky [Friedman] was the Ralph Nader of this race. If he hadn’t been in, Chris Bell would have won. Perry is a minority governor with less than 40 percent of the people behind him.” Brender believes that, with a strong presidential candidate at the top of the ticket in 2008 and the Republicans still floundering on the war, the Democrats could win back Tarrant County easily.

Then there’s that growing union presence at Alliance. All of the large transportation companies that have located there, Brender said, are union outfits, such as Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, UPS, and FedEx, and the pilots and airline mechanics are union as well. “This year, the local unions joined together as one and ran aggressive get-out-the-vote drives,” he said.

Doreen Geiger, Brender’s opponent in this year’s primary, said that candidates such as Pierson “exist in other districts in the county, and it’s possible for this to happen again with dedication of the proper resources.” One of the reasons Geiger challenged Brender was her frustration over “going to the polls and not finding enough Democrats on the ballot,” she said earlier. Given the number of names on the ballot this year, Brender seems to have gotten the message.

Geiger said her campaign was largely organized and run by Democrats who felt left out of the process and were ready to be involved, the same folks who need to be part of the process in the future. “To win back the county, the [party] needs to organize the emerging grassroots,” she said.

Eddie Griffin, an African-American human-rights activist here who claims loyalty to neither party, said, “Any notion of the Dems reclaiming the district or the county, like Dallas, is pure poppycock, without a strategic plan” and that the party chair still doesn’t have one. “Brender gave up on most of Tarrant County long ago,” he said.

Griffin faults Brender for putting most of the party’s money and resources into one race (Pierson’s) and letting the others be sacrificed. “He just assumed that those races weren’t going to be won. That’s not a winning plan,” he said. And he said, blacks here have been leaving the Democratic Party for years. “The so-called ‘black community’ is split as much as it can be.”

“Horse hockey,” Brender said. “Some black leaders have moved into the Republican camp, but the vast majority of black voters have stayed with us.” He cited the votes in two large, predominately minority precincts on the East Side where 98 percent of the ballots went to Democrats over Republicans this year. In fact, Brender said, the black vote is usually higher by about 20 percent for the Democrats than the Hispanic vote, reflecting the effect among Hispanics of the Catholic Church’s aggressive opposition to abortion and gay rights.

Hollern believes that the Republicans are natural allies of Hispanics “on our basic core values, the so-called family values issues: strong families, religion, pro-life. … Our star will continue to rise here for a few more years, and then it will wane, if we don’t go after the Hispanic vote and try and reach them on these common, shared values.” Hollern said it will take a massive commitment from Republican activists who must “go into their neighborhoods, into the barrios, reach out, and do real constituent service there.” But he thinks if it is done right, the Hispanic vote will be theirs.

No way, Gonzales said. Republicans “have spewed too many harsh anti-immigration words to convince us that they have Latino interests at heart. I’ve heard them say that they’re not anti-Latino, only anti-illegal immigrant. They forget that many Latino families have mixed legal statuses within the family. Dad and Mom may be illegal, but the children are not. I talked to several Latino students who walked out of school last spring. They kept saying that the anti-immigration legislation was an attack on their family. When you attack the Latino family, you’ve got a fight on your hands.”

But at the same time, he said, the onus is on the Hispanic leadership here. “Latinos need to become politicized. We need Latino leaders to speak boldly about taking political power. We don’t make enough noise, challenge the government, or protest the lack of Latinos in elected, business, education, and social service leadership positions.”

Dallas was successful in its change from red to blue, he said, because Latino leaders there “organize and grapple for power. Here, they don’t organize or demand political power.

“We’ve bought the malarkey that Dallas politics are rough-and-tumble but Tarrant politics are polite,” Gonzales said. “It saddens me to hear Tarrant Latinos mouthing these thoughts. That’s the thinking of Tarrant Anglos trying to hold onto their political grip as long as possible.”

Dallas County Democratic Party staffer Kirk McPike wrote on the party’s web site that “Dallas didn’t go blue by accident. It took hard work.” According to McPike, the Dallas Democrats started working in earnest more than a year ago after the election of a new county chairwoman, Darlene Ewing.

Dallas, with its solidly conservative reputation, had surprised the nation in 2004 when the county elected a Democratic sheriff who also happened to be Hispanic and not just a female but also a lesbian. It was also a wake-up call for the local party. Ewing recruited high-profile county Democratic veterans who began to aggressively and successfully raise funds. She hired new staffers and recruited a small army of volunteers, many of them students who got credit for their work. She sent them out to all quadrants of the city to organize the precincts and find people to fill vacant precinct chairs. Volunteers set up phone banks and walked targeted neighborhoods three weekends a month for more than a year. Most importantly, however, McPike wrote, was the party’s ability to recruit good candidates for every contested race and run those candidates as a slate. Many of the judicial candidates, he wrote, put their own money into their races and freed up the party’s funds for the less-well-financed candidates.

TVAC, also organized more than a year ago by wealthy Dallas County Democrats, raised money for the candidates and provided research, including uncovering what is now being called Condogate.

“While the Republican judicial incumbents did little more than show up at parades and write checks for nasty attack ads, our [judicial candidates] walked weekly, helped in our phone banks, and wore themselves out physically and financially,” McPike wrote. The result: The average Democratic Dallas County candidate won with a little less than 52 percent of the vote.

When Pierson takes her seat in the Texas House in January, she’ll do so knowing the debt she owes to minorities in her district. She said she plans to represent all her constituents equally, to be “fiscally and socially responsible,” and to avoid being labeled either a liberal or a conservative. During the race, she hardly allowed herself to be labeled “Democrat” — a distinction missing from her yard signs. But then, Goodman didn’t admit to being a Republican on his yard signs either. And that may be a clearer indication of changing times than even the election results.

Many think little will change for the district, except the loss of Goodman’s seniority and the side of the aisle from which the votes will be cast.

But from the Democratic Party’s point of view, “We will have one more voice and vote than we did two years ago,” Burnam said. In fact, the Democrats picked up six Texas House seats this November, not even close to regaining the majority they enjoyed for so long, but enough to energize the state party, just as Pierson’s win here has brought new energy to the local Dems.

As for her priorities in Austin, Pierson said education tops the list. To the delight of teachers, she has come out strongly against the TAKS, the accountability test imposed by George Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act that is the bane of teachers, students, and school districts nationwide. And like Goodman, she will fight to restore funds to the CHIP program and Medicaid, she said.

She doesn’t plan to make the legislature a career, she said, although she’d like to serve for a few more terms. “I think term limits are fine. This job ought to be shared by many of us.”

Her campaign had its own rough spots — some provided by her own party. Many condemned her for not being a “purist” because she openly courted Republican voters and, in one major gaffe, publicly praised Diane Patrick, the GOP opponent of David Pillow in the race for Kent Grusendorf’s former house seat. (Patrick won.) On one liberal-leaning area blog site she was roundly cursed for “endorsing” the Republican. “I never endorsed [Patrick]; all I said was she would make a good legislator, and I still think so, but I did apologize to David,” Pierson said.

“You can be a purist and never win,” she said, “or you can reach across both parties and talk to those in the middle, where most of us are.”

And who knows? Maybe when she hangs it up in a few more seasons a Latina will be waiting in the wings to take her place.

You can reach Betty Brink at bcbrink@earthlink.net.