At Hicks’ request, her mother, former Municipal Judge Maryellen Hicks, and some neighborhood association leaders were at the meeting, mainly because Hicks thought there might be a fight over the zoning changes — a fight with race at its center. Project developer Michael Mallick is Anglo, with offices on the west side of town. Those opposing Hicks and Mallick on the project are a few black business leaders, led by controversial real estate developer Leonard Briscoe, Sr., who went to prison in the 90s for illegal kickbacks. He contends that black developers like him are being aced out of projects in favor of white, politically connected developers like Mallick.

At Hicks’ request, her mother, former Municipal Judge Maryellen Hicks, and some neighborhood association leaders were at the meeting, mainly because Hicks thought there might be a fight over the zoning changes — a fight with race at its center. Project developer Michael Mallick is Anglo, with offices on the west side of town. Those opposing Hicks and Mallick on the project are a few black business leaders, led by controversial real estate developer Leonard Briscoe, Sr., who went to prison in the 90s for illegal kickbacks. He contends that black developers like him are being aced out of projects in favor of white, politically connected developers like Mallick.

Briscoe and his clan didn’t show up to speak out about the zoning change. But Hicks talked to them anyway. After the unanimous vote approving the zoning change, Hicks told the audience she was not “selling out” and that this deal was a “major moment and major turning point” for economic development in East Fort Worth, a long-neglected part of town.

And then Hicks let loose on the absent black business leaders. “There are those against any development in our community, and I’ll just leave it at that,” she said.

Others won’t leave it there, however. Even though many East Siders see Hicks as their political hope for the future, there are some who say she is overly sensitive and immature in how she deals with people — and that she comes to no decision or opinion without consulting her mother.

In the hallway outside council chambers, I approached former Judge Hicks to ask questions for this story. “I know who you are,” she told me. “You’re the reporter doing a hatchet job on my daughter.”

The Rev. Wendell “Buck” Cass, one of Kathleen Hicks’ stalwart supporters and advisors, moved in between us and pushed me away. “We don’t talk to papers like the Fort Worth Weekly,” he said.

When I tried to talk to the councilwoman after the meeting, Cass again moved to stop me, spreading his arms wide like a bodyguard. “I said we don’t talk to you,” he said. And Hicks, with whom I’d been trying to talk for weeks, walked away.

The problem? Maryellen Hicks was upset that the Weekly was interviewing community leaders who opposed her daughter. It was a rather odd response from a woman who has been active in politics for decades. Whenever a paper does a profile of a public figure, it is a standard practice to include the views of opponents. But Judge Hicks is very protective of her daughter, and that’s what gives some of Kathleen Hicks’ opponents the ammunition for the charge that the judge is the real council member, and not her kid.

Maryellen Hicks later apologized for her and Cass’ actions and explained what led to them. “I will never forgive or forget any of the unwarranted attacks that some men and women have made on my daughter,” she said in a phone interview. “They say that we hate uneducated black folks, that we are lighter skin color and feel superior. But it is all about my daughter not advocating one contractor over another.

Maryellen Hicks later apologized for her and Cass’ actions and explained what led to them. “I will never forgive or forget any of the unwarranted attacks that some men and women have made on my daughter,” she said in a phone interview. “They say that we hate uneducated black folks, that we are lighter skin color and feel superior. But it is all about my daughter not advocating one contractor over another.

“Yes, we talk about issues, but I spend most of my time in Houston now,” said Judge Hicks, who runs a legal mediation service. “My daughter is totally independent. I’ve told her many times that the worse thing she can do is have Maryellen Hicks telling her what to do. She doesn’t need it, and I don’t offer it.”

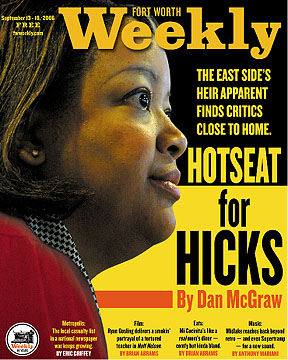

Regardless, Kathleen Hicks, at 34, is in the center of a controversy that has some African-American political and business leaders fuming. The charges are simple and trite, but the solution isn’t: If the best way to help a black area is, arguably, to bring in a white developer, what’s a black politician to do? Some black leaders think Hicks is selling out to the white business leaders and not taking care of her own constituents. Hicks and her supporters point out that she has made economic development a priority in her district and say she’ll back whatever projects are needed to rejuvenate her community.

Having this many people upset with her may be a strange experience for Hicks. For years, she’s almost been the golden child of Fort Worth African-American politics. Her mother brought her only child along to community events. Hicks grew up helping out on campaigns in her mother’s 12 years on the bench. Virtually everyone quoted in this story said they knew her from the time she was a child.

Hicks went on to the elite Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts (one of the “Seven Sisters” colleges) and earned a masters degree in international relations from Oxford University in England. She has lived in London, New York, and Washington and worked at a refugee camp in Kenya.

She served as assistant to former councilman Ralph McCloud for eight years before getting elected in 2005 as his replacement — with 92 percent of the vote in a three-person race. Most are proud that the little girl they all knew has blossomed into a strong leader on the council. But a few don’t like what the golden child turned into.

Ask community leaders about Hicks and their responses cover the waterfront.

“She is energetic and thoughtful and a breath of fresh air,” said Devoyd Jennings, president of the Fort Worth Metropolitan Black Chamber of Commerce. “I thought she would be more socially oriented, and I mean by that that she would think of the social obligations of her work more than business concerns. But she has worked hard, and the people in east and southeast Fort Worth are seeing some major economic developments.”

Bryan Muhammad, executive director of the Fort Worth/Tarrant County Millions More Movement, a group that advocates civil rights and economic development for African-Americans, isn’t so kind. “She is there to serve the massa’s business,” he said. “She thinks to herself, ‘I done tricked all you niggers already. Got your money, and I don’t want no problems with none of you-all.’ Kathleen Hicks is a total sellout. … She has no love for the constituents she represents.”

From Cleveland Harris, an Eastside barber who head ups the Morningside Neighborhood Association block watch: “She came in with two pistols like a Western sheriff,” he said. Hicks “has a positive attitude on what needs to be done and how to get people involved. … She was the missing piece to the puzzle.”

From Cleveland Harris, an Eastside barber who head ups the Morningside Neighborhood Association block watch: “She came in with two pistols like a Western sheriff,” he said. Hicks “has a positive attitude on what needs to be done and how to get people involved. … She was the missing piece to the puzzle.”

Edward Briscoe, who works with his father’s Briscoe Construction Corp., said Hicks has pulled a “bait and switch.” When Hicks was running for office, he said, “We talked with her about so many things, the importance of minority participation in contracts, the unfairness that had been shown against black businesses and contractors. She said she understood and agreed, she knew this and believed. She said her mother had the same problems when she was in private law practice. She said she had a firm grasp and she made commitments.”

Her commitments to black businesses included his family’s construction company, the younger Briscoe said. And the Briscoe family held fundraisers that brought in more than $5,000 for Hicks’ campaign, Leonard Briscoe said. “What she is doing now is totally hogwash,” Edward Briscoe said.

Why such disparate opinions? First, it’s probably unrealistic to expect all the black leaders in a city to agree, any more than it would be to expect all the whites to see eye-to-eye. But beyond that, the divide over Hicks seems to break down along old guard versus new guard lines. The Briscoes and Muhammad and former Judge Clifford Davis believe that one of the jobs of a black council member is to help steer the city contracts and city financial help to black-owned businesses.

“We have to be concerned about our community as a whole,” said Davis. “We don’t expect handouts. We only want the fair share. And that investment benefits everyone, from the top to the bottom. We need our council member to work on these issues, because economic development has always passed us by on the East Side.”

Those who support Hicks say that real economic development has never taken off in that part of town for a multitude of reasons — the flight of upwardly mobile blacks out of the old neighborhoods, a lack of interest at city hall, and a tradition of racial injustice that has begun to change only in recent years. Hicks and others believe that economic development will benefit the community no matter who does it — and that decisions should be based on quality of work and not on color.

Hicks “doesn’t control who the investors are,” said the Rev. Carl Pointer, pastor of the Greater St. Paul Missionary Baptist Church in the Stop Six neighborhood. “Developers have to have their own resources and reputation and professionalism. They have to have their own backing and know how to put a deal together.

Hicks “doesn’t control who the investors are,” said the Rev. Carl Pointer, pastor of the Greater St. Paul Missionary Baptist Church in the Stop Six neighborhood. “Developers have to have their own resources and reputation and professionalism. They have to have their own backing and know how to put a deal together.

“All of us who live in southeast Fort Worth think it would be fantastic for minority developers to pull off these major projects, just for diversity’s sake,” he said. But, “the reality is what the reality is.”

Fort Worth’s Southeast Side needs “more new homes, because more rooftops will satisfy the national retail interests,” Pointer said. “District 8 has 70,000 people and only one grocery store. We buy things like everyone else, and we can’t even get drugstores. We don’t have movie theaters or department stores. It is incredible. All we get are stores that sell 40-ounce malt liquor and cigarettes.

“So if a developer comes to our community, wants to work with us to change things, then I’m all in favor of it,” he said. “We have been watching this area become run down for decades, and nothing is ever done. But the change is happening, and I think we need to support our economic development interests no matter what race the person who is running it is.” It took a full month of e-mails and phone calls to get the interview, but now Kathleen Hicks is revving up into a passionate explanation of how she sees the challenges in her part of Fort Worth.

On a map leaning against the wall in her office, the councilwoman points out Cobb Park. A police officer once told her, she said, that the best thing to do with Cobb Park was to pave it over — and thereby get rid of the crimes that so often happen in its wooded areas. “We have an asset like Cobb Park that needs to be safer and used by our community,” she said. “We need to engage people and have them see we have some assets in place that can become the basis for wonderful neighborhoods.”

She points to the two Mallick Group developments on the map. The Sierra Vista development will provide about 230 new single-family homes on the site of the old Riverside Village apartment complex, plus retail sites nearby. About a mile to the east. the Masonic Home property will be transformed into about 500 homes plus 63 acres of commercial development. There will also be 16 acres set aside for natural gas drilling. Hicks helped broker a deal earlier this year that created a tax increment financing district to include both Mallick Group properties. As tax income to the city increases because of the development, the extra dollars will pay for infrastructure improvements — perhaps one of the few instances when Fort Worth has used the TIF device in the kind of blighted area it was intended for. The East Berry TIF could produce as much as $10 million for things like streets and sewers in what will be known as Masonic Heights, bounded by Wichita and East Berry streets and Mitchell Boulevard. Homes likely will sell for $140,000 to $200,000.

“We see all this development all over the city — TIFs in the Alliance Airport area and downtown and nothing over here,” Hick said. “In this time of growth for the city, it’s time to see some things occurring in this area. I’m not willing to dwell on the past anymore. I’m not going to sit here and occupy a chair.”

The difficulty in jumpstarting economic development “has been a real frustration of mine,” Hicks said. “Why don’t we get the nice streets and the public art over here? Why does everything stop at I-35 when you go east? If you want to see where people from southeast Fort Worth go grocery shopping, go to the Albertson’s near TCU on Saturday. People here have to drive 20 minutes to buy their food. It is pathetic.”

Fort Worth has “big-city issues now,” she said. “We can’t pretend we are some small town. This is a crucial time for us. We have to balance new growth with development in an aging central city. And it should happen — and is beginning to —on the East Side.”

Fort Worth has “big-city issues now,” she said. “We can’t pretend we are some small town. This is a crucial time for us. We have to balance new growth with development in an aging central city. And it should happen — and is beginning to —on the East Side.”

The bad feelings between Hicks and some black business leaders began when the city was deciding how much of the construction money on the new downtown Omni Hotel project should be set aside for minority- and women-owned businesses. Minority business owners wanted 25 percent, but developers and city council pushed it down to 15 percent, still about $15 million worth of contracts. Hicks voted for the 15 percent. “In the end, it was the largest participation of minorities in the history of the city,” Hicks said. “I gave it a lot of thought and felt strongly that the city was doing quite a bit to ensure minority participation and this would be a good economic engine for the city.

“The people who spoke about minority participation at that meeting — well, let’s just say they came down here and they were talking about one firm. Minority participation is for everyone to have a piece of the pie, and not just one firm. This is terribly important, because I represent 70,000 people and not just one entity.”

And what is that entity? Kathleen Hicks wouldn’t say, but everyone knows who it is. It’s Leonard Briscoe, Sr. and his development company.

Leonard Briscoe is as controversial as they get in Cowtown. He is a former city councilman and the first African-American from Tarrant County to get elected to the Texas House of Representatives. In the 1970s, he moved into the construction business, in part because the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban development was giving out more grant money to minority-owned businesses.

In the 1990s, Briscoe was twice convicted, for giving kickbacks and lying to government officials regarding low-income housing projects. In the first case, involving an elaborate payoff scheme to keep federal contracts flowing to his company, he was sentenced to two years in prison. In 1997, kickbacks were again the charge, and Briscoe pleaded guilty to giving false statements to government investigators, adding another 15 months to his time.

In the 1990s, Briscoe was twice convicted, for giving kickbacks and lying to government officials regarding low-income housing projects. In the first case, involving an elaborate payoff scheme to keep federal contracts flowing to his company, he was sentenced to two years in prison. In 1997, kickbacks were again the charge, and Briscoe pleaded guilty to giving false statements to government investigators, adding another 15 months to his time.

He does not hide from the convictions but says he is being treated unfairly by the city because of them and because of his race. What better way to make points with whites, he said, than by “fighting against some radical ex-convict like Leonard Briscoe or some black Muslim like Bryan Muhammad. Those are automatic things you can say to the white community and get a positive response. That’s what Kathleen Hicks is doing.”

But what about Briscoe’s record in business? His company has had some successes but also some stand-out failures: two bankruptcy filings and repeated cost overruns on projects. Some housing projects, like the 800-unit Regalridge apartment complexes, have been successful. But the bad projects are doozies. A $5.4 million contract to build an outpatient clinic for John Peter Smith Hospital in southwest Fort Worth ended up with $700,000 in cost overruns, and the company was eventually fired. At the Arlington convention center, the Briscoe work ran $200,000 over budget. The company has had numerous contracts with the Fort Worth Independent School District to build new schools and remodel and expand existing ones. Some, like the Clifford Davis Elementary School on Campus Drive, turned out well. But Briscoe has also argued with the school board about his fee, and last year, after years of legal wrangling, got the board to give him $242,000 more on a contract he’d bid at $572,000.

Leonard Briscoe Sr. defends his company and says he and his family should still be considered for contract work. “Every developer and construction contractor has successes and failures,” he said. “We are no different. But some of these factors were out of our control. When you work with government agencies, they often change the plans and cost overruns do happen.”

The latest controversy involves his longtime friend, Tarrant County Commissioner Roy C. Brooks, who sent out a letter on county stationery to two oil and gas drilling companies suggesting they form a partnership with Briscoe. The letter said Briscoe could help the companies negotiate mineral rights leases in minority communities in Fort Worth.

At the same time, the elder Briscoe had been appointed by the Glencrest Civic League, where Edward Briscoe served as president, to represent residents in negotiating mineral leases. Leonard sees nothing wrong with trying to represent the oil and gas drilling companies and the residents at the same time. “We just wanted to have one voice to represent all the property owners and to have the ability to get the best deal for the mineral rights,” he said. Brooks did not return phone calls asking for comment on his letter.

In Clifford Davis’ downtown law office, Leonard sat with seven other African-Americans, some talking on the record, others choosing not to. But meeting with a reporter to publicly criticize a sitting council member was quite odd, especially for a group that wants to get more work from the city. Leonard Briscoe, at 65, led the discussion, often interrupting his son to make points. Or rather, one point, made repeatedly: that the deck is stacked against them.

In the 1970s, Briscoe said, he led an unsuccessful but controversial lawsuit against the county when current Mayor Mike Moncrief was county commissioner, alleging that a county housing bond program excluded minorities. “Ever since then, Moncrief has had it in for me,” Briscoe said. “So now he has Kathleen Hicks do his bidding for him. … She wants to move on to higher office, so she needs his support. So she does what he tells her to do.”

Briscoe said he had bid on the Masonic Home property and was hoping to build homes and retail stores there. But the city’s promise of economic aid allowed Mallick to outbid him, Briscoe said. “We never even approached the city for any money. We would have done that after we did the deal, but I guarantee it would have been much less than what Mallick asked for.”

In an e-mail, Mallick wrote that his development plans have had the support of the whole council. “The claim that my company has obtained special treatment or favor from the City of Fort Worth because I am of a certain race has been made by an infamous, selfish real estate [company], who routinely demands inclusion as a special favor because of its owner’s race rather than a current successful track record,” he said. He declined to be more specific.

Hicks said the city was not involved in the Masonic Home property until after the land was sold. “We did not choose who to sell the property to,” she said. “The discussion about the TIF and any economic help to Mallick was all done afterward. I got off to a tough beginning with Michael Mallick when things first started. We knew what the community wanted, and he listened to the community. If he had wanted to put a package liquor store over there, we would have been all over them. But he listened to the community.”

Pointer agrees that Mallick satisfied all of the community concerns. “Is Michael Mallick my friend? No, we aren’t friends,” the minister said. “But I respect Michael Mallick because he hasn’t lied to me. He is an easy person to deal with because integrity is very important to him. He wanted community support and he listened to us. His integrity is the primary reason he got the support from the community.”

But Briscoe said the deal Mallick got will hurt Briscoe’s 155-home New Rolling Hills development in the same neighborhood, about a half mile away from Sierra Vista and Masonic Heights on Old Mansfield Highway. “We don’t object to white businesses doing business in our community,” Briscoe said. “What I do mind is when we develop 155 lots, the most we can get from the city was a $275,000 loan. We are in a competitive market. The city gave Michael Mallick $4 million. Cash. They gave him money for demolition. We had demolition too. It cost us $300,000 to make our site useful.

“So all we want is a level playing field,” Briscoe said. “And our council representative should work on our behalf. She isn’t doing that.”

But even Briscoe’s New Rolling Hills is not exactly working out well. KB Homes recently pulled out, citing grading problems, according to a report on WFAA-TV. No homes have been built in more than a year.

The other dispute is between Mallick and the Briscoe family, and it is more personal. Edward Briscoe contends that Mallick has been telling business and political leaders that Briscoe approached him, trying to get hired as a consultant for the project as a way to keep the community opposition at bay. “Mallick is telling people that we told him that if you want to do business over in that area, you have to come through us,” he said.

The younger Briscoe said he’s only met Mallick a couple of times and that they “never discussed a consultant contract.”

In his e-mail, Mallick didn’t answer Edward Briscoe’s accusation directly. He wouldn’t discuss the issue further.

The Fort Worth City Council has changed quite a bit in the past few years. It is younger, more ethnically diverse, and has more first-term members. Donavan Wheatfall, Sal Espino, and Hicks all represent minority districts and aren’t the type to sit back and wait for the crumbs to fall. Carter Burdette, Danny Scarth, and Jungus Jordan are also in their first terms, and none seem to be wedded to the old ways of doing things.

“When I would go to meetings … we used to hear about new projects in the Alliance corridor or the West Side or downtown,” Devoyd Jennings, the chamber of commerce president, said. “But when they got to the East Side, there was never anything to say. Now they talk about that part of town. Development has been done in all parts of the city, but not over here. But that is changing. … We want to be part of the growth, and that is so important for the city on so many levels.”

Wheatfall also sees a difference. “I think we have become a more progressive council that is looking more closely at the other Fort Worth, not just the new growth areas at the fringes,” he said. “We are paying more attention to areas that have been long underserved.” He’s critical of Hicks for her vote on the Omni Hotel minority contract percentage, but said “that issue has been dealt with and we’ve moved on.” And Hicks has an “an innovative approach … a new sense of energy,” he added.

People like Espino and Hicks’ predecessor Ralph McCloud echo those sentiments.

“Kathleen Hicks is a conscience of the council,” Espino said. “She advocates for those who don’t have the same services and economic chances as those in the other parts of the city. The ‘other Fort Worth’ has some great challenges now, and we are addressing them.”

McCloud, director of pastoral and community services for the Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth, said he sees “a shift in how southeast Fort Worth is being viewed. I spoke loudly and boldly about the issues, but council always gave preference to those on the other side of town. We tried to draw attention to the needs of this area, but the Westside leadership didn’t even know the other side of town existed. We have to draw attention to it, and Kathleen is doing it.”

While Hicks is trying to figure out how to please the old guard and the new leadership at the same time, she’s also dealing with a reputation for occasionally being a no-show and hard to get hold of.

The group in Clifford Davis’ office complained that their phone calls to her are not returned quickly. And she didn’t show up for U.S. Rep. Michael Burgess’ Eastside economic summit last month, though Moncrief, Wheatfall, Brooks, and about 100 business leaders made it. Hicks was visiting her mother in San Antonio.

“It is really rather odd that she is not here,” said one city staffer at the meeting. “This is really her show.”

Hicks says she returns all calls quickly, attends neighborhood meetings, publishes a newsletter for her district, and is available to those who need her help. “For those who say I am unavailable is not true,” she said.

Her relationship with Moncrief is also another sore point with some in her district — though many would think that being able to work closely with the mayor would be a good thing for the East Side, not a problem.

“She and the mayor are joined at the hip right now,” said one high-ranking elected official. When Moncrief wanted councilman Chuck Silcox out as mayor pro tem, according to sources, he steered the largely ceremonial job to Hicks. Moncrief did not return phone calls for this story.

“I see a change right now, and much of the change has happened since Kathleen Hicks has been in office,” said Ida Piper, president of the Morningside Neighborhood Association. “The mayor is now paying attention to this area, and we like that. It means things will happen.”

And many in the neighborhood think the old guard needs to get out of the way. The Briscoes “don’t like Kathleen Hicks because she knows how to talk to people, and she is honest with her dealings with us,” said barber Cleveland Harris. “The Briscoes are about what they can get out of the situation. … That attitude stalled a whole lot of things. The whole Omni Hotel situation wasn’t about minorities from their perspective. It was about Briscoe being able to get contracts.”

Hicks could have taken the politician’s traditional easy way out on the Omni contract — voting for the higher minority set-aside while knowing that the lower number would pass. Only Wheatfall voted against the deal.

“Mayor Moncrief never told me how to vote on the Omni project,” Hicks said. “I gave it a lot of thought, and there were a lot of issues here. And once again, this was a large minority percentage, and this is not about one contractor.”

But the Omni vote is still reverberating in some quarters. “We have black contractors to do this work,” said Bryan Muhammad. “But people like Kathleen Hicks and Moncrief are spending time and energy trying to demonize black contractors so they have the excuse that black contractors don’t have the capacity to do this work.”

Hicks just shrugs off comments like that. “The Riverside Village property had been available for about 20 years to develop, and no one ever did it. Oakwood Mall has been vacant since I was a kid, and anyone can buy that property and make an investment,” she said. “So there are opportunities to take advantage of, and I will work with anyone who wants to invest in this community.”

As for the talk that she might succeed Moncrief if he doesn’t run again, Hicks said, “My mother and I laughed about that question, because I have never even thought about that.”

“This is a crucial time for this part of town,” she said. “All over the country, cities are seeing their old neighborhoods close to downtown as vital assets for revitalization. We can do that here. But we have to have the citizens who live in those areas decide what they want. We have to work with developers and national retail chains. Because all we have over there now is a bunch of convenience stores that sell malt liquor and cigarettes. No other part of the city would permit that.”

People like Cleveland Harris and Ida Piper and Rev. Carl Pointer think that decades of experience show the old guard’s approach didn’t work very well.

“This is America, and whether we want to admit it or not, race plays a part in almost everything we do,” Pointer said. “It is who has the money and who has the votes.” In southeast Fort Worth, “we are taking charge, and I think the city is finally listening. There has been acceleration under Kathleen Hicks. … Some don’t like the changes. But we have to move forward. Because if we don’t do it now, it will never happen.”

You can reach Dan Mcgraw at dan.mcgraw@fwweekly.com.