It wasn’t the winds that turned New Orleans into a disaster zone, but the flooding that, in the course of a few hours, changed the image of a soul-rocking city cradled by a mighty river into that of a bombed-out Third World war zone — and did major damage to a president’s image as well. With 80 percent of New Orleans under water, the country that had put men on the moon took days to evacuate hospitals, and broadcast to the world the scenes of thousands of desperate people trapped on freeway ramps and at a sports stadium while bureaucracies floundered around them.

It wasn’t the winds that turned New Orleans into a disaster zone, but the flooding that, in the course of a few hours, changed the image of a soul-rocking city cradled by a mighty river into that of a bombed-out Third World war zone — and did major damage to a president’s image as well. With 80 percent of New Orleans under water, the country that had put men on the moon took days to evacuate hospitals, and broadcast to the world the scenes of thousands of desperate people trapped on freeway ramps and at a sports stadium while bureaucracies floundered around them.

In the year since, the floundering has continued, deepening the questions not only about New Orleans’ future but the future of coastal communities from Texas to New York City. On the anniversary of the storm, video images still showed — alongside a thriving French Quarter — dead neighborhoods, abandoned streets, houses etched with brown waterlines like domestic shells after a neutron bomb. With only roughly 200,000 of the pre-Katrina population of 463,000 back, scattered areas are still without electricity, and the city’s water system is still losing millions of gallons a week, due to thousands of leaks that the city’s reduced work force still hasn’t plugged. Repairs will cost about $2 billion — but there’s no funding package in sight. The levees still aren’t fixed against another major storm. People who need FEMA trailers as temporary housing still don’t have them, while other trailers sit vacant. And after a deadline set this week, thousands more who have not yet been able to repair their damaged homes may find them seized and demolished by the city, a policy being fought by some community groups.

It’s been clear since those refugees gathered at the Superdome that the natural disaster of the storm was equaled or dwarfed by the governmental disasters that followed it. But in the ensuing months it has also become clear that even the storm itself was more than just a natural disaster. The evidence is piling up to suggest that the great flood that followed Katrina was in large part a man-made tragedy.

The problem goes beyond the flaws in New Orleans’ levee system and the shoddy system of federal emergency preparedness that the storm laid bare; it involves a pattern of incredible incompetence at many levels of government, going back decades. The most profound of the problems that Katrina exposed was the impact of climate change — creating what some activists are calling “climate refugees” — in a country that continues to ignore the need for a different kind of defense policy, an environmental defense policy, to protect coastal communities as well as those far inland.

The problem goes beyond the flaws in New Orleans’ levee system and the shoddy system of federal emergency preparedness that the storm laid bare; it involves a pattern of incredible incompetence at many levels of government, going back decades. The most profound of the problems that Katrina exposed was the impact of climate change — creating what some activists are calling “climate refugees” — in a country that continues to ignore the need for a different kind of defense policy, an environmental defense policy, to protect coastal communities as well as those far inland.

Katrina was a billboard for global warming. For decades, emissions from fossil fuels used by industry and automobiles have sent carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, thinning the ozone layer, the protective membrane that softens the sun’s penetrations. As a result, a long melt is under way in Greenland, Antarctica, and the South Pole. The melting ice causes seas to rise. As seas rise, so do their temperatures, in hot months. Hotter air and warmer water ignite more powerful storms.

The hottest year on record, 2005, saw the greatest concentration of hurricanes with record winds — Katrina, Rita, and Wilma. The summer of 2006 has brought continuing destruction, only more spread out.

“We’d have to go back over three decades to find anything comparable to the flooding we’re seeing in the Northeast,” National Weather Service meteorologist Dennis Feltgen told USA Today in late June, referring to the wash of destruction in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, and even New York. The Big Apple is by no means safe from flooding: In December 1992, a northeasterly storm sent the sea level up by eight feet at the southern edge of Manhattan Island. LaGuardia Airport had to close, the Brooklyn tunnel flooded, and the subway system shut down.

In his new book The Ravaging Tide, Mike Tidwell writes that a rise in sea level of one to three feet will have an impact on “every inch of American shoreline from the Texas coast to the Florida Keys to the Outer Banks of North Carolina to Cape Cod. The low-lying areas of San Diego and San Francisco and much of Puget Sound on the West Coast are at great risk too.” He cites an EPA study that found “no fewer than one in four U.S. buildings within 500 feet of a coastline will be destroyed by erosion by mid-century.”

Flooding is America’s most common natural disaster. In the decade before Katrina, flooding caused $7.1 billion in losses to homes and businesses. As the intensity and frequency of major flooding increases and more people buy flood insurance, the financial pressure on the federal government — which backs flood insurance — will escalate in kind.

Flooding is America’s most common natural disaster. In the decade before Katrina, flooding caused $7.1 billion in losses to homes and businesses. As the intensity and frequency of major flooding increases and more people buy flood insurance, the financial pressure on the federal government — which backs flood insurance — will escalate in kind.

“Hurricane Katrina’s $23 billion [insurance] hit has triggered a full-blown debate about the federal program that insures property in flood-prone areas,” author Neil Peirce wrote recently in Stateline.org. “Critics are charging [that] the program’s rates are so cheap and its loopholes so broad that it actually puts pressure on local governments to permit new development in extraordinarily flood-prone areas — territory that should never be built on in the first place.”

Tidwell asserts that the damage from global warming is even more widespread. The last 30 years have seen a temperature rise of five degrees in Alaska. He cites a four-million-acre “forest of spruce trees so vast it’s bigger than the state of Connecticut — yet every single spruce is dead.” The dead forest (a distant cousin to New Orleans’ dead neighborhoods) is caused by a spruce beetle reproducing at twice its normal rate. The result, Tidwell wrote, “is the largest forest die-off by insect infestation ever recorded in North America.”

Al Gore has been working to bring attention to the global warming problem since he was a U.S. senator. This year’s An Inconvenient Truth, the film based on Gore’s ongoing lectures (and the title of his companion book), shows stark scenes of glaciers crumbling and the browning of Mt. Kilimanjaro in Kenya — gone are the snowcaps Hemingway adored.

But President Bush, backed by a majority of Congress, has officially scorned the idea of global warming. Sen. James Inhofe (R-Oklahoma) calls global warming “the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people,” comparing the science behind it to Nazi propaganda leading up to World War II. And Exxon Mobil Corp., which has much to lose from the measures to reduce global warming, has fought to discredit the theory even as the scientific consensus on the problem has only grown stronger.

In 2001, Bush rejected the Kyoto treaty on reducing global warming; since the U.S. is one of the world’s greatest producers of greenhouse gases, that meant that the possibility of reducing those emissions worldwide became much slimmer.

In 2001, Bush rejected the Kyoto treaty on reducing global warming; since the U.S. is one of the world’s greatest producers of greenhouse gases, that meant that the possibility of reducing those emissions worldwide became much slimmer.

But as scientific data mounts, many people are taking a harder, deeper look. Tidwell reported, for instance, that Britain’s largest insurance company in 2002 “predicted that unchecked global warming could bankrupt the entire global economy by 2065.” A key threat, the insurance giant concluded, “was sea-level rise that would directly destroy valuable land, buildings, and agricultural assets while indirectly exposing everything farther inland to more intense storms expected in a warmer world.” It’s no secret that human (and mostly governmental) error contributed tremendously to the New Orleans flood — huge flaws in Mississippi River levee projects built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and environmental negligence by governments and oil companies that caused wetlands south of the city to erode. The lost wetlands gave tidal waves an open alley to the city.

But maybe you haven’t heard that the government, as a help to business, actually paved the way to New Orleans for the hurricane.

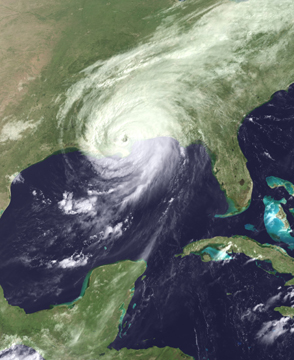

In the 24 hours before Katrina made landfall, the storm doubled in size, blanketing a California-size area of the Gulf, according to John McQuaid and Mark Schleifstein in another new book, Path of Destruction. As the Category 5 storm with 175 mph winds neared Louisiana, its winds dropped to 127 mph, still strong enough to produce huge waves.

Katrina hit early on Monday, Aug. 29. It flattened the coastal town of Buras, sending thunderous waves across villages and hamlets south of the city, tossing cars and boats onto trees and roofs. Winds roared across Lake Borgne, pushing waves 20 feet high. The giant water sheets rolled toward New Orleans East on a passageway between canals. One side of the vast lane reaches a levee along the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway; the other levee hugs the eastern side of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, known locally as MR-GO (pronounced, without a trace of irony, “mister go”), an alternate shipping lane finished in 1963 to move cargo from the Mississippi to the Gulf. The “funnel,” where the Intracoastal and the MR-GO meet, sent water between and over the tops of those levees and into the city as well as nearby St. Bernard Parish.

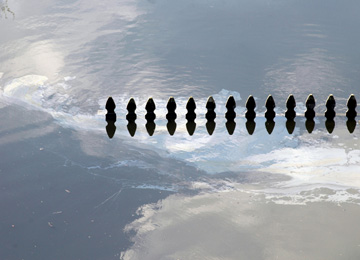

The funnel is the end result of decades of dredging by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Building MR-GO destroyed 20,000 acres of marshland in the 1960s. Junior Rodriguez, the barrel-chested president of St. Bernard Parish, railed against MR-GO for years. The dredging opened an artery 500 feet wide.

By 2001, as Christopher Hallowell wrote in Holding Back the Sea, a prescient book on wetlands loss, “Erosion from ships and storms has gouged it 2,000 feet wide and made it a freeway to New Orleans for any hurricane that happens to come from the right direction.” Hallowell saw the shape of things to come. “The surrounding marsh, now vulnerable to storms and salt water, has all but died … along with 40,000 acres of mature cypress trees. Now, storm surges can invade the marsh through the straight-arrow channel and smash into New Orleans.”

The smashing happened before, in 1965, when Hurricane Betsy hit New Orleans. Kenneth Ferdinand, an African-American real estate investor and urban planner, grew up in the Lower Ninth Ward, just across the Orleans Parish line from St. Bernard. In recent years, he sat in regional planning meetings with Rodriguez, sharing his hostility to MR-GO.

Betsy’s surging waters rushed up MR-GO, burrowing into the levee along the Industrial Canal, which divides the Ninth Ward into upper and lower sections. When the Industrial Canal levee broke in ’65, a large swath of the Lower Ninth was inundated, drowning 81 people. Ferdinand went into his grandfather’s house to claim his body after Betsy. “I’ve seen this catastrophe twice in my lifetime,” he said. “The difference between Betsy and Katrina is that the flooding was much worse. And Katrina wrecked those communities below the Lower Nine” — St. Bernard and, further south, Plaquemines Parish.

Betsy’s surging waters rushed up MR-GO, burrowing into the levee along the Industrial Canal, which divides the Ninth Ward into upper and lower sections. When the Industrial Canal levee broke in ’65, a large swath of the Lower Ninth was inundated, drowning 81 people. Ferdinand went into his grandfather’s house to claim his body after Betsy. “I’ve seen this catastrophe twice in my lifetime,” he said. “The difference between Betsy and Katrina is that the flooding was much worse. And Katrina wrecked those communities below the Lower Nine” — St. Bernard and, further south, Plaquemines Parish.

The Lower Nine and St. Bernard Parish were destined to flood because of MR-GO. Even Louisiana’s Republican U.S. Sen. David Vitter — who prior to Katrina promoted legislation to allow commercial destruction of cypress trees — has come around to saying that the 76-mile canal should be closed. Such a move would allow for some of the lost wetlands to be restored.

An investigation by the National Science Foundation after Katrina found flaws by the Corps in the engineering design on canal floodwalls that were meant to drain water into Lake Pontchartrain — the 17th Street and London Avenue canals that became the stars of so much helicopter video coverage.

Yet alongside the Corps’ mistakes and FEMA’s incompetence, the city bears a measure of blame. The city’s levee district in the early 1980s pressed the Corps to confine its design scope to a 100-year hurricane defense, which meant the city would pay proportionally less for its cost-share of levee work, thereby freeing funds for lakefront development. The Corps wanted to build canal floodgates in the lake, which might have prevented flooding in much of the city.

The flooding put in sharp relief a central challenge to south Louisiana’s survival: coastal erosion and how to remake wetlands as a protective buffer against Gulf hurricanes. The damage was chronicled by Hallowell, by Times-Picayune reporters Schleifstein and McQuaid in a 2002 series, and by Mike Tidwell in his 2003 book, Bayou Farewell, among others.

The land south of New Orleans has been sinking as Gulf waters rise. Tidwell found fishing communities with submerged cemeteries, people whose property had disappeared into the Gulf. A million acres of wetlands have been swallowed, eroding nature’s defense against hurricane tidal waves, opening a destructive path to the city.

But the dynamics of this failure are national in scope. Louisiana Gov. Mike Foster (1996-2004) gave petrochemical industries an easy ride for toxic waste disposal, treating his Department of Environmental Quality like a serfdom. But Foster, a bluff, Falstaffian fellow, liked the great outdoors and became concerned about coastal erosion thanks to a cross-section of business people, fishermen, industrialists, state officials, and ecologists who collaborated on a long report in 1998 called Coast 2050: Toward A Sustainable Coastal Louisiana. Foster personally gave George W. Bush copies of Hallowell’s and Tidwell’s books. There is little evidence that he read them. Coastal 2050 estimated it would cost $14 billion to restore the lost wetlands — big money, but a fraction of the $200 billion in estimated losses from Katrina. In 2004, Bush cut the Corps’ funding request for levee maintenance by more than 80 percent.

The sinking of Louisiana’s southern parishes will be replicated in other rural and metropolitan areas along the Atlantic coast as ocean levels rise. For now, the Louisiana case is more severe; it stems in part from 20,000 miles of pipelines that crisscross the coastal floor to deliver oil and gas from offshore rigs. Many canals are long abandoned, yet continue to erode and widen. The levees built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in response to the Great Flood of 1927 are another well-recognized factor in the equation. Containing the Mississippi’s currents with stronger levees kept the city safe from the river but bottled up diversionary outlets, which drove streams of river silt like a chute into the Gulf rather than letting the sediment generate sluiceways to replenish tidal marshes — or for that matter, Texas beaches. Starved of river nutrients, gouged by pipe excavations, the wetlands eroded and lower Louisiana began sinking.

Nearly 25 percent of all the oil and gas consumed in America travels through Louisiana’s wetlands. Roughly a quarter of the nation’s seafood was generated from Louisiana’s coastal area before Katrina. Since 1932, the state has lost 1,900 square miles of wetlands, an area larger than Rhode Island. Ten square miles disappear annually.

“The cost of a collapsing coast is one of fundamental survival,” said Mark Davis, director of the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana in Baton Rouge, a group that has worked on the issue for years. “What happened last year was also the failure of a value system. We assumed we had tamed the forces of nature. We need to understand that if we want there to be a New Orleans or a Los Angeles or a Miami or a New York 500 years from now, we can’t assume they’ll be there. We have to plan for them to be there. That’s why the rise in sea levels and freshwater management are so extraordinary.”

As Davis runs down a list of other cities — including San Francisco, Orlando, and Atlanta — where rapid growth has overwhelmed environmental-defense planning, it is worth noting that FEMA considers New Orleans, Miami, and New York as the cities most vulnerable to hurricane disasters. More than a third of the 167 hurricanes that struck America in the last century hit Florida. Miami is about three feet above sea level, with a vast wetlands complex to the west. Beachfront development and a building boom have packed the area with people. If the ocean levels continue to rise, the area’s marshy buffer won’t be enough to halt a massive flood — another potential disaster waiting to happen.

Streams of Hispanic workers have flocked to New Orleans for construction jobs, giving the city an Alaskan boomtown air (except without the cold or the gold) that will probably remain for the next few years. Music and strip clubs will hum; the spirit of jazz and spontaneous cultural improvisations will roll like a wave from the soul. But the now-less-populous city, with fewer schools, is still stalked by poverty and crime, as drug dealers fight for smaller pieces of turf. It is hard to imagine any of that changing for the better, given the fractured New Orleans Police Department.

Streams of Hispanic workers have flocked to New Orleans for construction jobs, giving the city an Alaskan boomtown air (except without the cold or the gold) that will probably remain for the next few years. Music and strip clubs will hum; the spirit of jazz and spontaneous cultural improvisations will roll like a wave from the soul. But the now-less-populous city, with fewer schools, is still stalked by poverty and crime, as drug dealers fight for smaller pieces of turf. It is hard to imagine any of that changing for the better, given the fractured New Orleans Police Department.

So the city will produce for tourists and conventions the spectacles and cuisine for which it is known, while low-end workers who staff the hotels and restaurants struggle to find housing. In all of this, the dead silence of absent leadership — Mayor Ray Nagin’s — hangs like a heavy fog in the muggy night. New Orleanians cry out for a comprehensive recovery plan, but Nagin has effectively punted that idea back to the citizens, offering a “plan for a plan,” putting the onus on neighborhood groups, a process that will take at least until the end of this year to produce anything. By then, billions in federal aid that has been sent down to the Louisiana Recovery Authority, a state agency conceived by Gov. Kathleen Blanco, will have been committed to other parishes that have already adopted recovery plans.

The contingent of Republicans in Congress who’d just as soon not see New Orleans rebuilt aren’t crying in their beer, of course. “A relief bill passed by the GOP House in March managed to omit critical funds for battered levees,” The New Republic editorialized on Aug. 8. “At times, negotiations stalled because some Republicans tried to divert Katrina relief away from Louisiana.”

An odd thing has happened in the storm’s aftermath. While the conservatives they’d helped put in Congress were treating New Orleans as expendable, like an outer edge of the Third World, scores of churches from red states were sending volunteers to the muddy blue city at the bottom of America, gutting houses, cleaning streets, helping people recover. Some evangelical ministers have started to speak out about global warming, fraying the edges of GOP unity on the topic.

But in the ensuing year, the Democrats failed to make an issue of Katrina — why the flood happened, how to prevent future ones. Perhaps the portents of mass ecological breakdown are so huge a migraine that no one wants to touch it — except the environmental lobby, the media, and Al Gore.

“Environmental defense” — that is, a strategy to keep other Katrina-like disasters from occurring, to rebuild wetlands and stop or slow global warming — is not an issue in most people’s minds. The stirrings of a Louisiana plan to prevent future disasters are based on that idea, though no one is calling it that.

On Aug. 1 the Senate approved a bill by U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) to give Louisiana and other Gulf states a 37.5 percent royalty on 8.3 million acres newly designated for drilling in the Gulf, providing an estimated $200 million annually in the next decade to combat coastal erosion. A House version of the bill by U.S. Rep. Bobby Jindal, a Republican who represents suburbs of New Orleans, called for higher royalties, netting $2 billion a year. A compromise measure working its way through a House-Senate conference should give the state sorely needed funds for coastal defense projects.

For her part, Gov. Kathleen Blanco sued the federal Minerals Management Service to halt a scheduled lease of oil and gas exploration in the Gulf, arguing that the agency ignored environmental damage caused by offshore drilling. A windfall in offshore royalties would give the state some leverage in shoring up erosion and preventing future destruction. On Aug. 14, a federal judge denied Blanco’s request to halt the lease but warned potential bidders that the state is likely to prevail in its argument, which could stop drilling on the leased tracts.

For now, there is no institutional mechanism to rebuild the eroding coastline. Mark Davis, the outgoing director of the coastal restoration coalition, said that “awareness is at an all-time high, but the decision-making apparatus is not there to do what needs to be done. It’s like watching a revival movement, with everyone talking about how good heaven is, but you don’t see a great shift in behavior as if people are planning to get there.”

Davis, who has worked with everyone from bank presidents to shrimpers, faults a forest of red tape and a slough of inertia in Washington. Even if revenues materialize, the state lacks jurisdiction over levees and navigational structures — they fall under federal authority. “The state’s ability to change is not just a question of money,” he said. “Blanco has come to the realization that the state has to lead the federal government to the answers.” He lauds the governor for suing the minerals management agency, saying that she has sent a message that the feds must participate in rebuilding the coast.

What kind of institution should guide coastal restoration? And how do you pay for it? “A big problem with major environmental projects is that Congress authorizes funds that take forever to materialize,” said Davis. The lag in delivering promised federal money has delayed restoration of the Everglades and a California project to prevent flooding from the Sacramento River that threatens San Francisco Bay. Finding a dependable revenue stream is a big hurdle. The congressional appropriation process must be gone through each year, with endless negotiations over special interests.

The Tennessee Valley Authority delivered electrification to the middle South during the Great Depression, as a federal agency. Why couldn’t a similar agency rebuild Louisiana’s wetlands as part of an Atlantic coastal protection agenda, with immunity from Congressional pork-barreling?

Whatever the mechanism necessary for a solution, it is way overdue. The only way to prevent the disaster scenarios that Gore, Tidwell, and others put before us is with a mass campaign to reduce global warming. A policy that rewards industry for cutting carbon dioxide emissions, developing energy-efficient cars and homes, and shifting the economy from dependency on fossil fuels may seem unreachable in this maddened time of terrorism and oil wars. But the alternative is to sink into a deeper passivity of consumerism. Couch potatoes at the apocalypse, we’ll fill up at $5 a gallon and head for the heartland each time the next big one comes, trying not to collide with sweaty nomads from Alaska heading south, all of us carrying a memory of the flood.

Jason Berry is a New Orleans writer whose books include Lead Us Not Into Temptation, Vows of Silence and a novel, Last of the Red Hot Poppas, to be published in September.