Gardner lost his job after taking a leave of absence, which he thought had been approved, to attend a training academy for a second job. It turned out his leave had not been approved through the proper chain of command, and he came home to find himself fired. Then his right to file a grievance was denied, his appeals were denied, and he was left with a large stain on his job record, courtesy of Tarrant County.

Gardner lost his job after taking a leave of absence, which he thought had been approved, to attend a training academy for a second job. It turned out his leave had not been approved through the proper chain of command, and he came home to find himself fired. Then his right to file a grievance was denied, his appeals were denied, and he was left with a large stain on his job record, courtesy of Tarrant County.

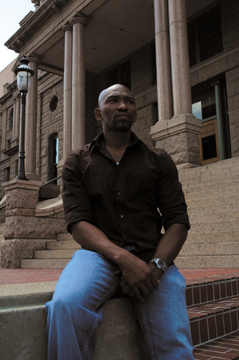

For the last six years, Gardner has been fighting an uphill battle to get his day in court — and to explain why, from his point of view, he didn’t abandon his job, didn’t deserve to be fired, and does deserve the chance to explain his version of the story. It’s been six years of depositions, hearings, and legal briefs going back and forth. The loss of the job and the ensuing court costs have caused him to file Chapter 7 bankruptcy, but Gardner hasn’t given up. He still wants county officials to be held accountable, he said.

Neither Assistant District Attorney Robert Browder, who has been defending Tarrant County in the case, nor anyone from the Tarrant County Civil Services Department would comment until the appeals process is over.

The nightmare began in 2000, when Gardner, a juvenile probation officer, decided he needed to get a second job, both for the added income and because he wanted to save money to go back to school to get his master’s degree. Already working full-time on the night shift, he found a part-time day job with the local office of the state’s adult parole agency, but it required three weeks of training at the Parole Officer Academy in Beeville.

On Sept. 11, Gardner got permission from his immediate supervisor, Setrick Dickens, both for the second job and for taking the time off the following month. Dickens agreed with Gardner’s plan to use seven days of vacation time, plus arranging with a co-worker, Todd Mateja, to cover the rest of Gardner’s night shifts while Gardner took Todd’s usual weekend shifts.

However, two weeks later — three days before he was to leave — Gardner got the bad news in a phone call. Hope Brockway, the senior casework supervisor over Dickens, called to say that she had approved neither Gardner’s leave nor the second job. In court depositions, Brockway said Dickens had failed to get her required approval. She refused permission, she said, because of concerns over possible conflicts of interest that could arise from the parole job. Brockway subsequently gave Dickens a written warning and suspended him for three days.

Gardner asked Brockway what he should do; she told him he should think about resigning if he went ahead and took the time off. After a little more discussion, Gardner maintains, Brockway then told him to go take the training, and they would “sort it out” when he got back. When he asked if he should work his weekend shift, he said, the supervisor told him that he was being “taken off the schedule,” and someone else would cover the shifts.

Brockway’s version, told in sworn depositions, is that she told Gardner he needed to report to work on the days he was regularly scheduled — but indeed not to come in on the weekends, because those shifts were still technically assigned to someone else.

Gardner’s wife, Leslie, was on the line and heard the conversation. “Ted, point blank, asked her … what she suggested he should do. She said to go to the training, and they would sort it out when he got back,” Leslie Gardner said. And, she said, Brockway did not tell Gardner to come in to work.

So Gardner went to his training, thinking things would be cleared up when he returned. Back in town after the first week, he contacted Dickens, who said he had no information for him. He then returned to training for weeks two and three, each weekend trying to contact his supervisor. Finally, on Oct. 14, Dickens told him he wasn’t allowed to talk to him about the matter and referred Gardner to another supervisor — who also didn’t return his calls.

The answers Gardner couldn’t get from Dickens or the other supervisor came soon enough by mail. Two letters, from different department managers, alleged that Gardner had abandoned his job and that the officials had taken steps to “remove your name from the payroll of Tarrant County.”

Gardner got both letters on Oct. 24. He tried to talk to the assistant department directors, to no avail. Then, on the same day he received the letters, he tried to file a grievance protesting his dismissal.

From Gardner’s point of view, that’s when the second Catch 22 came into play. Civil Service Coordinator Ann Smith told him he couldn’t file a grievance because he hadn’t been fired yet. But when he tried again on Nov. 3, she told him it was too late to file a grievance, as more than seven days had passed since he had been fired.

The problem was, Gardner said, the probation department managers never told him the date of his firing. Nor did the letters advise him of his right to file a grievance, as required by the Civil Service rules.

Gardner hired a lawyer and received a hearing on Nov. 13 before the Civil Service Commission. At the hearing, the two commissioners, using the date of the Oct. 24 letter as his firing date, ruled that Gardner indeed had not filed his grievance within the proper timeframe. Minutes of the meeting show that commissioners refused to allow Gardner’s lawyer, Sue Allen, to present evidence contesting his firing, insisting that the only issue before them was whether the grievance had been filed in time.

“They said I knew the rule and didn’t follow it. They didn’t want to hear the reason why,” Gardner said.

Six years later, it’s still the same story. Gardner and his second lawyer, Jay Gueck, filed a lawsuit alleging wrongful termination and have gone through numerous motions but have never been allowed to present Gardner’s side of the story. They’ve never had a chance to explain why Gardner thought he had permission to take leave, why he feels he didn’t abandon his job.

“If they felt they were right, then let me go to my hearing,” Gardner said.

On Feb. 13, 2006, District Court Judge Len Wade granted Tarrant County’s motion for summary judgment without comment. In April, he denied Gardner’s request for a new trial.

Gardner and his attorney have now appealed Wade’s decision to the state appellate court, still seeking a new trial. If that appeal is not granted, the next stop is federal court — if Gardner can afford it.

“I had a right to a second job. I had a right to file a grievance. I had a right to file a complaint with Civil Service. I had a right to present evidence at the hearing. And I had a right to file a lawsuit” said Gardner. But “with Tarrant County, you just don’t question their authority. You do whatever they tell you to do.”

Gardner still works for the state parole agency, but he transferred to Denton County in 2003.

So why does he continue a fight that so far has won him nothing but legal bills? As someone who works with parolees, Gardner said, he’d like to be able to tell them that the system works.

“It makes you not believe in the system,” he said, “and I hate to be like that.”