On May 21, Lance Cpl. Benito Ramirez — a “valley boy” from Edinburg in South Texas, and “Cheeks” to his friends — was in the turret of the armored humvee, hunkered low in the sling seat so as not to draw sniper fire. In the turret, there’s never any shade, and the wind in his face that should have brought relief felt like standing in front of a blow dryer set on “hot.” Ahead, all the traffic dutifully pulled off the road as they approached, even the pedestrians and the bicyclists. Locals knew that these Marines — from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, known as the 3/5, who’d helped take Fallujah back in 2004 — didn’t kid around.

On May 21, Lance Cpl. Benito Ramirez — a “valley boy” from Edinburg in South Texas, and “Cheeks” to his friends — was in the turret of the armored humvee, hunkered low in the sling seat so as not to draw sniper fire. In the turret, there’s never any shade, and the wind in his face that should have brought relief felt like standing in front of a blow dryer set on “hot.” Ahead, all the traffic dutifully pulled off the road as they approached, even the pedestrians and the bicyclists. Locals knew that these Marines — from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, known as the 3/5, who’d helped take Fallujah back in 2004 — didn’t kid around.

The sergeant major was in the cramped seat behind the driver (where the best air conditioner vents are located); the lieutenant was in the front right seat manning the radios. With any luck they’d have time to stop by the mess hall at Al Taqaddum Airbase — known as TQ — for some Baskin-Robbins ice cream. This might be Iraq, the temperature might top 106 every day, the food and their quarters might be marginal, but by God at the mess hall at TQ a righteous Marine could get all 31 flavors. Strange, but not any stranger than many of the other facts of this war.

Take the rules of engagement and escalation-of-force requirements. On Route Michigan, if an oncoming civilian, perhaps just jockeying for a place to pull over, didn’t get off the road fast enough, Cheeks and the Marines would first have had to wave an international orange flag at the driver. Next, a flare would be shot above the vehicle. If it still didn’t stop, that would be followed by a warning shot into the pavement and then one into the grill. Finally, if the vehicle kept coming, the Marine would be authorized to fire a “kill shot” at the driver himself. Imagine a 19-year-old Marine processing all this information in less than 10 seconds, with the innocent driver/possible suicide bomber within 200 yards and coming closer. Imagine that, if he does pull the trigger, even if the oncoming driver is not hit, the Marine will have to justify his action to an inquiry held by military lawyers. And imagine that if the Marine doesn’t shoot, the next thing that happens might be a car bomb blowing up next to his vehicle and the other Marine vehicles behind him. And then the 19-year-old wouldn’t have to face an inquiry because he’d probably be dead.

Cheeks knew all that, maybe better than most. After all, he wasn’t 19 on that day in May, he was all of 21, a friendly, witty guy but also an experienced warrior, a respected veteran of “The Push,” the action in November 2004 when thousands of Marines swept through Fallujah, destroying the insurgent resistance in some of the most vicious, hand-to-hand fighting that the Marines have waged in half a century. This was war the Marines could understand.

But this patrolling day after day — this isn’t The Push. It’s the slow, deliberate crawl that is the reality of war in Iraq in 2006. And it’s proving to be just as dangerous a mission as The Push — perhaps even more so, because the objective, like the enemy, is so amorphous and getting murkier every day.

The thing that many of the veterans of The Push can’t get their heads around is how this could happen. Fallujah has gotten worse, not better, since the 3/5 was here last. After that initial battle and the house-to-house “back clearing” stage that followed between Thanksgiving 2004 and New Year’s 2005, Fallujah, the “City of Mosques,” for a time resumed its character as a peaceful town where Marines and soldiers could drive to the market — in unarmored, open vehicles, without helmets or body armor — for fresh fruit and vegetables or even stop at a local restaurant for a meal, welcomed by local merchants and citizens, with neither group fearing an attack.

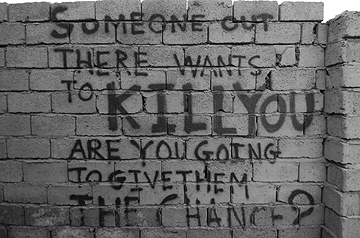

But now Fallujah is slowly sliding back into chaos. It’s happening in spite of a powerful American military presence and in spite of the continued rebuilding of the country’s infrastructure. It’s happening because the Iraqis understand that one day soon — even if that day is a couple of years away — the Americans and their Western allies will be gone. And the insurgents, the common criminals, and the foreign fighters from groups like al Qaeda, will still be there — armed with names of informers and collaborators and with scores to settle.

But now Fallujah is slowly sliding back into chaos. It’s happening in spite of a powerful American military presence and in spite of the continued rebuilding of the country’s infrastructure. It’s happening because the Iraqis understand that one day soon — even if that day is a couple of years away — the Americans and their Western allies will be gone. And the insurgents, the common criminals, and the foreign fighters from groups like al Qaeda, will still be there — armed with names of informers and collaborators and with scores to settle.

The Marines know it, too — no matter their bravery, no matter how much they believe in their country, the mission, their commanders, and the Marine Corps, no matter how much they try to ignore the politics of this war. Nearly every one of the young Marines of Lima are finished with Iraq and the Marine Corps at the end of this enlistment. They’re done, worn out from the constant separation from friends and families. The running joke is that Marines get “care packages” from Iraq, because they’ve been there more in the last four years than they’ve been in the U.S. The career Marines, those with eight or more years of service, are opting for “B” billets — that is, choosing to become instructors, guaranteeing they won’t have to deploy to Iraq again for three years.

But while they’re “in country,” every day, like Cheeks, they go out to drive the roads and walk the fields and palm groves and see if this is the day that an IED — an “improvised explosive device,” the real killer of this phase of this war — or a sniper will get them.

I, on the other hand, understood none of this when I managed to get myself to Iraq a few months ago as an embedded reporter. A former Marine and longtime photojournalist, the father of a young Marine newly deployed in Iraq, I intended to stay for three months. But within a month, I had learned the lesson of Iraq. And I came home.

Creeping down the middle of the road at 10 miles an hour is not how most Americans imagine the war in Iraq is being fought. Many people who continue seeing televised images of pitched battles, with bombs and missiles raining down on a hapless and defeated foe, have no idea that those graphic videos, for the most part, are almost two years old. But the daily crawl in heavily armored humvees continues to be one of the most dangerous and vital missions that members of Lima Company of the 3/5 carry out in western Fallujah.

Lima (pronounced like the city in Peru, not like the bean) Company’s roughly 300 Marines live and work out of two Forward Operating Bases located about four kilometers apart on the western bank of the Euphrates. This vast Mississippi-like river provides a formidable natural barrier on the outskirts of Fallujah and, with only two bridges leading into town, a perfect location for checkpoints. Everything along the river bank is lush and green, with numerous canals splitting off to crisscross the landscape. In the evenings it’s anyone’s guess which there are more of, mosquitoes or bats. But a mere 50 yards away from the river, all traces of moisture have disappeared, leaving a layer of cement-colored dirt that wafts upward in response to the slightest movement or breeze, coating everything in a gritty powder. The constant dust diffuses the light and makes it harsher, masking the shape of the immensely powerful sun, making it look like something out of Dante’s Inferno.

Lima (pronounced like the city in Peru, not like the bean) Company’s roughly 300 Marines live and work out of two Forward Operating Bases located about four kilometers apart on the western bank of the Euphrates. This vast Mississippi-like river provides a formidable natural barrier on the outskirts of Fallujah and, with only two bridges leading into town, a perfect location for checkpoints. Everything along the river bank is lush and green, with numerous canals splitting off to crisscross the landscape. In the evenings it’s anyone’s guess which there are more of, mosquitoes or bats. But a mere 50 yards away from the river, all traces of moisture have disappeared, leaving a layer of cement-colored dirt that wafts upward in response to the slightest movement or breeze, coating everything in a gritty powder. The constant dust diffuses the light and makes it harsher, masking the shape of the immensely powerful sun, making it look like something out of Dante’s Inferno.

The two sand-colored fortress-like buildings at FOB Black sit about a mile from the metal trusses of the so-called Blackwater Bridge, where in late 2004 four civilians from the Blackwater Security firm were brutally killed by insurgents. The televised images of their burned and mutilated bodies hanging from the bridge prompted outrage from the American public and led to the eventual capture of Fallujah.

FOB Gold’s two buildings are located about four kilometers west of “Black” down a two-lane blacktop road pockmarked with IED scars. At both bases, 10-foot-tall reinforced concrete walls surround the compound. Layers of green sandbags block the windows and “HESCO” barriers, large metal mesh frames supporting a dirt-filled durable liner, provide additional protection from snipers, rocket-propelled grenades (RPG’s), and random mortar attacks. Camouflage netting covers areas of the roofs where movement is necessary, providing some level of shade and sniper protection to machinegun positions. Compared to their last deployment, these are great “digs,” with hot food, some air conditioning, occasional internet service, and a gym.

“Gold” is strategically located on one of the two major east-west highways leading from Fallujah to Ar Ramadi, the now hotly contested capital of Al Anbar province, making the base extremely important to combat operations in western Iraq. Lima Company’s job is keeping these two main supply routes, Route Michigan to the north and Route Boston in the south, open for the long truck convoys that, nightly, carry all kinds of material westward through Fallujah’s deserted streets to the massive Al Taqaddum Airbase. These convoys support the thousands of personnel stationed at TQ and are vital in carrying the fight to the remainder of the restive Al Anbar province.

Keeping the routes open means keeping them clear of IEDs — either they find and disable the IEDs or the IEDs find them. These roadside bombs, built of everything from small homemade explosives to massive 122mm artillery shells, can produce small irritating explosions that flatten a tire or puncture a radiator — but the powerful ones can obliterate a vehicle, no matter how well armored, along with those inside.

It’s a job that has to be done over and over: Drive down a road, and the locals in the shops, sitting over smokes and tea, wave at the Marines. Drive back 20 minutes later, and an IED takes out a humvee, and the old men and the boys who’ve been sitting there have seen nothing. In the months since Lima has been in Fallujah there have been over 100 IED “incidents.” “It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when” his young Marines are going to get hit by an IED, says Gunnery Sgt. Brett Turek, at 38 the “old man” of the company. He received a very personal reminder of the dangers of Iraq in February, when a suicide car bomber rammed an explosive-filled gasoline truck into a new base that Turek was helping build. He was wounded and all of his unit’s vehicles were destroyed, but he didn’t lose any of his young Marines. “I’m not going to kid you,” said one 20-year-old from Ohio, “IEDs are the only thing I’m afraid of over here.”

It’s a job that has to be done over and over: Drive down a road, and the locals in the shops, sitting over smokes and tea, wave at the Marines. Drive back 20 minutes later, and an IED takes out a humvee, and the old men and the boys who’ve been sitting there have seen nothing. In the months since Lima has been in Fallujah there have been over 100 IED “incidents.” “It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when” his young Marines are going to get hit by an IED, says Gunnery Sgt. Brett Turek, at 38 the “old man” of the company. He received a very personal reminder of the dangers of Iraq in February, when a suicide car bomber rammed an explosive-filled gasoline truck into a new base that Turek was helping build. He was wounded and all of his unit’s vehicles were destroyed, but he didn’t lose any of his young Marines. “I’m not going to kid you,” said one 20-year-old from Ohio, “IEDs are the only thing I’m afraid of over here.”

About half the time, the patrols find the IEDs before they explode and have engineers dismantle or destroy them. As for the other half of the time: “About 70 percent of the company has been involved in attacks,” said Lima’s executive officer, 1st Lt. Josh Burgess. Most members of the mobile assault platoon, who do most of the IED sweeps, have been “blown up” at least once, although improved body armor and humvee armor saved most from serious injury. The Marines in Fallujah have developed an uncanny ability to spot many of the IEDs. Sometimes it’s a trash pile out of place, disturbed dirt, or a plastic bag. Other times it’s the lack of locals, especially children, on the streets or in front of their shops, that tip them off.

I sat outside “Gold” one morning about 6 a.m., thinking how cool and peaceful it was, almost like being home in Texas. Then an IED went off about 500 meters down the road. No injuries or casualties, but a giant wake-up call for me. Later, on a day when we had just returned to our patrol base from a foot patrol, we heard that the group who’d gone out immediately after us had suffered a sniper attack. Five minutes later, someone drove by and fired an RPG at our position and missed.

I spent three weeks with Lima, doing everything and going everywhere that they did. We spent hours talking politics and sports, telling stories about The Push, and watching movies. The amazing thing is just how little the average Marine knows about The Big Picture. They don’t care. Since it doesn’t affect their day-to-day situation, they don’t waste any time thinking or worrying about it. Most of their precious little time off patrol is spent cleaning weapons, trying to keep the dirt and sand out of their living quarters, and sleeping. They never get enough sleep. Heavy workloads mean that instead of six days off per month, the Marines at Lima got only about four days off duty in almost seven months. Meals come twice a day, and showers, depending on water deliveries, happen every four to five days — if there’s time to take them.

Like most Americans in similar situations, the Marines of the 3/5 want to see themselves as helping people. But the longer they stay in Iraq, the more cynical and angry they become. After a generation living under a ruthless dictator, truth and directness in dealing with authority don’t come easily for most Iraqis. The young Marines see the uncertainty and half truths — but not always the reason. More than once, during searches of houses and people, I heard Marines say, “The only thing I hate worse than this shitty country are these lying bastards. Why can’t they just tell the truth?” There is a palpable disdain for Iraqis caught in a lie.

Like most Americans in similar situations, the Marines of the 3/5 want to see themselves as helping people. But the longer they stay in Iraq, the more cynical and angry they become. After a generation living under a ruthless dictator, truth and directness in dealing with authority don’t come easily for most Iraqis. The young Marines see the uncertainty and half truths — but not always the reason. More than once, during searches of houses and people, I heard Marines say, “The only thing I hate worse than this shitty country are these lying bastards. Why can’t they just tell the truth?” There is a palpable disdain for Iraqis caught in a lie.

Despite all the danger, during the time I was with Lima, nobody in my immediate vicinity ever got shot or blown up. People started wanting me to ride with them. I was the lucky charm. I made a lot of friends, talked a lot of shit, learned to actually enjoy the occasional MRE. But I was never afraid, at least not for myself. And up until I left, none of Lima’s Marines had been killed by the IEDs or snipers.

Once I got home, I obsessively checked the casualty reports several times a day to make sure everyone was still safe and OK. Well, they weren’t. As I write, 10 Marines, most from the 3/5, guys whom I met and hung out with, are dead, all but one from IEDs.

For my first week in Iraq, before hooking up with Lima Company, I spent time with a unit called Bravo 1/1. Out on my first night patrol with them, the commanding officer told me that, if we were attacked, the rules for embeds were out the window, and I could use the turret gunner’s weapon, since I’d trained on something similar during my days in the Marines. For five nights with Bravo, I slept in the cot next to the company gunnery sergeant’s turret gunner, Cpl. Ryan Cummings of Streamwood, Ill. We bullshitted, told lies, talked about women, drinking, and raising hell when we got home. On patrol, he was careful — always sat way down in the sling seat, wore all the protective gear he could find, always stayed alert to his surroundings. But when an IED flipped over his humvee, he was partially ejected and crushed to death.

And for what?

For the American troops, places like Fallujah must seem more and more each day like some deadly Middle Eastern version of the Hatfields and McCoys, with explosive charges taking the place of squirrel guns and the American military caught in the middle.

Intimidation through violence permeates the entire spectrum of Iraqi society. No one is safe. Barbers, bakers, vegetable vendors, or parents walking their children to school can be the victims of mindless explosions or attacks perpetrated by militant groups in and out of official uniform. If a car is stopped at an Iraqi police checkpoint and the driver and passengers know the policeman, his family, or friends, does anyone really believe the policeman or soldier will arrest them or inform on them if they have a trunk full of illegal weapons? And it’s the Iraqi police and Army troops who are manning more and more of those checkpoints.

Another growth industry in Iraq is kidnapping. Wealthy families in larger cities are beginning to disguise themselves as poor and needy, hoping this will offer them some measure of protection from the kidnappers. It doesn’t. The kidnappers are usually people from the neighborhood but not from the same tribe or clan.

That tribal/clan mentality complicates the situation for the Marines. A personal slight or just bad blood can have deadly consequences. If Marine intelligence or Iraqi Army units receive information about a weapons cache or explosives hidden at a house or in a field, they will move into the area to question and possibly arrest suspects. If contraband is found, the most relevant question becomes whether the tip-off was a good deed or a lie to cause a neighbor grief. Many Iraqis have found that they can use the Americans to settle old scores. Iraqis know what clan and tribe their neighbors are from and what they do for a living and often have very strong feelings about those clans and businesses. In the end there are no simple answers, no simple solutions — not for the Iraqis who are living in fear and getting killed and not for the Marines in the field fighting and dying.

That tribal/clan mentality complicates the situation for the Marines. A personal slight or just bad blood can have deadly consequences. If Marine intelligence or Iraqi Army units receive information about a weapons cache or explosives hidden at a house or in a field, they will move into the area to question and possibly arrest suspects. If contraband is found, the most relevant question becomes whether the tip-off was a good deed or a lie to cause a neighbor grief. Many Iraqis have found that they can use the Americans to settle old scores. Iraqis know what clan and tribe their neighbors are from and what they do for a living and often have very strong feelings about those clans and businesses. In the end there are no simple answers, no simple solutions — not for the Iraqis who are living in fear and getting killed and not for the Marines in the field fighting and dying.

The creeping instability tainting every aspect of the ordinary Iraqi’s life comes from the Iraqis’ understanding that their relationship with the Americans and the West is a terminal one. Many Iraqi politicians, living in relative opulence and safety in Baghdad’s “Green Zone,” aren’t in any hurry to improve their country’s security situation because they’d like to keep the Americans there as long as possible, to come to their aid if all goes bad. But at some point, the Americans and their allies will be gone. Having spent billions of dollars and used up countless lives, Iraqi and American, the Americans will be through, finished, done. Left behind will be the sectarian and political factions who have infiltrated the police force, the Iraqi Army, and the Interior Ministry with their own personal agendas, vendettas, and old scores to settle.

Many of the Marines I talked to about these things said they didn’t care — they just wanted to get home in one piece. Some realize they’re in the middle of a civil war they can’t stop and that it will ratchet up to full-blown the second the last American leaves. But most don’t think about it, since they can’t do anything about it.

It affects them anyway, of course. For one thing, while the explosives and snipers and tanks make Route Michigan look and feel very much like a war zone, the rules read more like those that might be imposed if martial law were declared in an American city. The rules of engagement in fact are much stricter than those that many U.S. police departments operate under. And, just like American cops, Marines and soldiers frequently have to explain to investigators the split-second decisions they made on their urban battlefields.

Early in Lima’s deployment, 19-year-old Lance Cpl. Mack McSperitt fired a round through the windshield of an oncoming car. The driver was hit only by flying glass, not by the bullet, but McSperitt was filled with questions: Had he followed the rules? “Did I do all the steps right?” His squad leader, Cpl. Nick Jeffries, a big tough kid from Spokane with a massive tattoo of a compass on his shoulder, reassured him that everything would be fine. He had seen what McSperitt had seen — he’d back him up. In the end the military investigators agreed, and any suggestion of punitive action was dropped. What had caused this near-deadly confrontation? As the convoy approached, the driver of the other vehicle couldn’t see the Americans because of the glare on his windshield.

Early in Lima’s deployment, 19-year-old Lance Cpl. Mack McSperitt fired a round through the windshield of an oncoming car. The driver was hit only by flying glass, not by the bullet, but McSperitt was filled with questions: Had he followed the rules? “Did I do all the steps right?” His squad leader, Cpl. Nick Jeffries, a big tough kid from Spokane with a massive tattoo of a compass on his shoulder, reassured him that everything would be fine. He had seen what McSperitt had seen — he’d back him up. In the end the military investigators agreed, and any suggestion of punitive action was dropped. What had caused this near-deadly confrontation? As the convoy approached, the driver of the other vehicle couldn’t see the Americans because of the glare on his windshield.

The night before I left Fallujah, I ran into two Marines with whom I’d been on a raid. I asked if they were going home on R&R, and they both laughed. No, they said, they had to go to Baghdad for a couple of days to testify about what they’d found in the raid. How many wars have there been where soldiers — while the war was still going on — had to leave the line to go testify in a criminal trial?

It was a full house. Every one of the white plastic chairs was taken, and the bare gray concrete walls of the Habbaniyah Chapel, located next to 3/5’s new headquarters at an old abandoned British air base, were lined with friends and comrades in arms. Everyone was there to say their final farewells, perhaps gain some closure, or try to make sense of this death.

Lance Cpl. Ramirez — Cheeks, who’d made it unscathed through The Push and a second deployment in Iraq and five months of his third — had been killed by shrapnel from an artillery-round IED that peeled apart the layers of laminate and steel of his humvee. A piece of metal literally found the chink in his armor, entering under his armpit, above his new “sappy plates,” designed to protect Marines from projectiles coming from the side. Others in the humvee were injured, but they recovered.

Cheeks always had a smile on his face and something funny to say, and he could motivate anyone. He had planned on going back to Edinburg to work in his father’s trucking business when he completed his enlistment. I’d talked to him briefly at 3/5 command post. And of course everyone around him was laughing at something he’d said.

Ramirez was assigned to the battalion’s personnel security detachment, the Jump Platoon. His battalion commander, Lt. Col. Patrick Looney, an intense, intimidating, leader, spoke at the memorial service. “He had a quick and sharp wit, and you could always count on Cheeks to lighten the mood or bust your chops,” Looney said. “If there was a leader to the lance corporal mafia, it was Cheeks.” In battle, Looney said, Cheeks was focused and fearless — that’s how he ended up being the gunner in the sergeant major’s humvee.

Ramirez was assigned to the battalion’s personnel security detachment, the Jump Platoon. His battalion commander, Lt. Col. Patrick Looney, an intense, intimidating, leader, spoke at the memorial service. “He had a quick and sharp wit, and you could always count on Cheeks to lighten the mood or bust your chops,” Looney said. “If there was a leader to the lance corporal mafia, it was Cheeks.” In battle, Looney said, Cheeks was focused and fearless — that’s how he ended up being the gunner in the sergeant major’s humvee.

During the service, battle-hardened Marines who’d fought next to Cheeks cried openly and hugged each other. His friend, Cpl. Jason Morrow, who had served with Cheeks during The Push and had known him since infantry school, talked about him. Staff Sgt. Raymond J. Plouhar offered up the Marine’s Prayer. Afterward, they gathered in small groups to tell funny stories about their buddy.

I rode out to my first embed assignment with Morrow and Plouhar. A week later, the two were killed in almost the same spot as Cheeks. And the next day, the other Marines saddled up and went back out to keep the road open — for what?

The Marines I met in Iraq who died in action: Lance Cpl. Benito “Cheeks” Ramirez, Staff Sgt. Benjamin Williams, Staff Sgt. Raymond Plouhar, and Cpl. Jason Morrow, all of the 3/5, but not from Lima Company. From Bravo 1/1, Pfc. Steven Freund, Lance Cpl. Robert Posivio III, Cpl. Ryan Cummings, Pfc. Christopher White, Lance Cpl. Brandon Webb, Staff Sgt. Benjamin Williams. And Lima Company’s only casualty, killed by a sniper at FOB Gold only weeks before his deployment ended, Pfc. Rex Page.

Don Jones is a North Texas freelance journalist. He can be reached at lopull@airmail.net. His son, whose assignment does not put him on the streets of Fallujah, is still in Iraq.