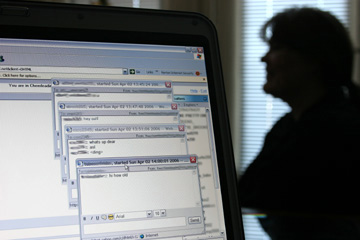

Within minutes, a middle-aged man from a Fort Worth suburb who was also pecking at his keyboard, lured the teen into a 51-minute rambling exchange that the man eventually steered toward sex.

Within minutes, a middle-aged man from a Fort Worth suburb who was also pecking at his keyboard, lured the teen into a 51-minute rambling exchange that the man eventually steered toward sex.

He wanted to know what the girl looked like — was she thin, did she have tattoos, was she white? What did she do for fun, did she have a boyfriend, had she ever had sex, what was her fantasy? Then he directed the conversation toward X-rated fantasies of his own involving an under-age teen-age girl and a man old enough to be her grandfather.

“How big r breasts for me, baby?” he asked. “Would you cheer for me in a thong if I pleased you all over.” He told he her wants to make her “shake with electrifying ecstasy.’’ She answered his increasingly personal questions. They talked of getting together and the lies to tell her parents. “You seem sweet, fun to talk to and so sexy,” he said.

“When is the best day to meet?” he asked. “Maybe Monday to Wednesday next week — I really want to know you better.”

“OK,” she answered. “We can talk more.”

“Act some too,’’ he said. He gave her his cell phone number and told her to call. They said their goodbyes.

As things turned out, the teen-age cheerleader didn’t meet her cyber-suitor. In fact, a rendezvous between them would have been impossible because the girl was nothing more than a fictitious online profile created by Jane Patterson, a 40-year-old Fort Worth native who has joined the growing ranks of citizens who are taking not the law, but the outing of potential pedophiles into their own hands.

“When you enter the [chat] room, your ID pops up and they just jump on you,” Patterson said. “Even if these guys are not going to ever meet the child, they are certainly giving them an online sex education of the worst kind.” Many of these public outings have taken place on a web site run by a group called Perverted Justice — PJ, for short. PJ volunteers pose as minors, enter chat rooms, record their exchanges with men who want to have sex with children — just as Patterson did. Then they take the chat to the police. If the cops aren’t interested, they post the chat for the world to see. There are so many pervs eager to make anonymous dates with minors that the site’s founder, Xavier Von Erck, has told reporters that catching predators is easier that shooting fish in a barrel. “These fish,” he said, “are jumping in the boat.”

While the group’s tactics are viewed skeptically by many in law enforcement, some agencies have begun to work with PJ. The site, which was created four years ago, claims to have provided “the basis for well over a hundred search warrants and arrests,” including some 60 convictions in 26 states. (Three of those convictions took place in Texas.)

If these sorts of sexual gotchas sound familiar, that’s probably because you’ve seen one of NBC Dateline’s “To Catch a Predator” programs. The show is a twisted version of Allen Funt’s Candid Camera — news teams with hidden cameras confront men who show up for sex dates they’ve made online with PJ volunteers. That show was, in fact, what inspired Patterson to go online in the guise of a vulnerable teen-ager looking for companionship

When she was a teen-ager, Patterson said, she dodged inappropriate advances by older men a couple of times and heard stories about dirty old men trolling Six Flags and skating rinks for young girls. She was shocked to see on television that a new generation of molesters was now trolling ubiquitous internet chat rooms and social networking sites— and curiosity got the best of her.

“Sometimes you really don’t believe what you’re hearing,’’ she said. “I was doing an experiment.”

Although all the man had done to Patterson was talk, she knew that Texas lawmakers, in an effort to crack down on internet crimes against children, last year broadened the ban on the sexual solicitation of children. The new law, which took effect Sept. 1, made it illegal to solicit not only actual minors, but also people posing as minors. In an internet chat room, it’s often impossible for one person to know with any certainty who they might be talking to — a middle-aged woman posing as a 12-year-old boy, a minor posing as a adult, or a grizzled police veteran pretending to be a vulnerable ingenue.

“Even if it is an adult portraying himself [as a minor], as long as the person soliciting believes the person is under age, it doesn’t matter,” Patterson said.

She saved her chat word-for-word on her computer and verified as best she could the man’s identity. He apparently lives in a nearby suburb, is married, and has a child. Armed with what she thought was evidence of a crime, she contacted Fort Worth police. Naïve as the girl on the internet, she thought the cops might quickly make a case. That, however, was six months ago, While police have begun to work the case, they have yet to make an arrest.

The man who wanted to have sex with Patterson’s imaginary teen-ager, according PJ, seems to have plenty of company.

A Tarrant County man in his mid-20s told a PJ volunteer posing as a 14-year-old girl in an online chat all the naughty things he planned to do as soon as they get together, then added he could get “in a hella lotta trouble.” A Dallas County man in his late 20s invited a volunteer pretending to be a 14-year-old virgin to spend the night drinking beer at his house, even as he told her he’s “too old for you for sure.” In Denton County, a 21-year-old man sent a nude photograph of himself to, he thought, a 12-year-old girl, then suggested that he wanted her to do something of a sexual nature to him with a carrot.

None of those men has been arrested or prosecuted, however, because the evidence against them, like the chat Patterson saved, was gathered by civilians, and lots of cops don’t want to build cases on anything other than evidence they themselves develop. Although a small number of law enforcement agencies are warming to the group and its tactics, most remain reluctant to make cases on information gathered by private citizens.

Much of the investigation of online sexual solicitation of children and child pornography throughout the country is overseen by a network of 46 Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) task forces that investigate allegations of child pornography and solicitation around the country. Until recently, a five-officer unit within the Dallas Police Department served as the sole task force in Texas working such cases. That changed in May when Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott announced that his Cyber Crimes Unit had received a grant to form a second task force for the southern half of the state. Dallas police will continue to handle the northern half.

The Dallas ICAC task force is headed up by Lt. C. L. Williams. He says the unit spends most of its time investigating cyber-tips from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children or posing as minors online in various chat rooms. His team will accept “ a referral from anyone who wants to give it to us.”

The Dallas ICAC task force is headed up by Lt. C. L. Williams. He says the unit spends most of its time investigating cyber-tips from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children or posing as minors online in various chat rooms. His team will accept “ a referral from anyone who wants to give it to us.”

“We’d be glad to take it and work it from the beginning, making sure we have all the evidence lined up and there is no entrapment,” he explained. But his office is not going to make a case against someone based solely on a private chat — no matter how explicit.

“It’s a tricky and slippery slope to get on,” Williams said. “I’m not going to go into court … and testify to the veracity of some private citizen. I don’t know how you do that.”

The recent law change, however, is apparently spurring some local law enforcement agencies to step up investigations of online sexual solicitation cases. Lake Worth, for example, has two of its 31 officers working on such cases, said Police Chief Brett McGuire. So far, they’ve made seven arrests —including those of a bottling plant worker, a computer engineer, a Marine Corps sergeant, and a student. Of his small department, he said. “I don’t know anybody our size who’s doing the same thing right now.”

And he said he wouldn’t rule out trying to make a case based on a private citizen’s chat. But much of the decision would turn on how the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office viewed the evidence. “We’d see if we could get the ball rolling, at least take a run at it,” McGuire said.

Denton police spokesman Jim Bryan said his department has made about 15 arrests since the law was changed. And the department did investigate the incident on the PJ web site involving the man who was interested in having carrot sex with a minor. The man, he said, actually lived in nearby Krum, and the complaint was turned over to that city’s police department. What happened to it since, however, is not clear. Krum police did not return a call from Fort Worth Weekly.

The reluctance of some law enforcement agencies to make cases based on civilians’ evidence seems even more remarkable in contrast to the willingness of cops in other parts of the country to do just that. Police in Laguna Beach, Calif., recently presented Perverted Justice with a plaque of appreciation. Police in Riverside, Calif., worked with PJ to make 21 arrests. In Texas, of 21 archived PJ chats, three have resulted in prosecutions, two by the FBI and a third by military officials.

One of those the site takes credit for was the conviction of a Lubbock man on child pornography charges, following an investigation by the FBI. According to court records, Paul Mark Burton, using the screen name “hum-366,” used Yahoo! Instant Messenger Service to send video of a man masturbating to a person he thought was a 13-year-old girl he met in a “14 Thru 17 Only” chat room. According to federal court records, Burton told federal agents that he engaged in similar chats with as many as 30 other minor females and as many as 50 adults. The FBI also found child pornography on Burton’s computer.

PJ founder Von Erck said that, without his organization, there would have been no prosecution. “The only reason they seized his hard drive is we brought it to the forefront,’’ he said. PJ gave the feds its chat log with hum-366 and “they acted upon it,” he said.

In that particular case, Von Erck said, PJ approached law enforcement about the incident before posting the chat online. When the group found no takers, they went ahead and put the chat on the web site. “Then we got lots of interest.”

The agent who worked the case, Keith Quigley, referred questions about it to a federal prosecutor, Steve Sucsy. The assistant U.S. attorney said he could not comment on the specifics of Burton’s case, but he said the FBI is reluctant to use citizens “in any other capacity except as witnesses” because “then we’re responsible for how they operate.

“Whatever the information the citizen is giving you, if you can make a case with it through more traditional law enforcement methods, then that’s a possibility,” he said. Sometimes, he added, that won’t work. Burton, meanwhile, was sentenced last week to seven years and three months — on a case brought to the FBI by Perverted Justice.

One of the problems law enforcement has with civilian cases is the potential baggage. Does the person complaining about a chat have a previously existing relationship with the suspect? Are they trying to settle an old score? Did the volunteer bring up the topic of sex or wait for the suspect to do so?

“Chats and other information from Perverted Justice must be judged on a case-by-case basis,” said Bryan, the Denton police spokesman. “Some of the things they are able to do would be considered entrapment if a law enforcement agency did the same thing, and it would not be allowed in court. One example of this is the mention of sexual acts by the Perverted Justice people before the suspect mentions it. This is not legal for a police department to do.”

Added Dallas Police Lt. Williams: “Just because someone says, ‘I got hit on and here’s our conversation,’ that’s not enough for us to file a case. We have to make sure we know who we’re dealing with.”

For the public, knowing who you’re dealing with when you’re dealing with PJ isn’t easy. Although site members’ identities sometimes become public, the managers and “contributors” to the site use pseudonyms, many straight from the shelves of our consumer culture, such as Almond Joy, Big Mac, and Kit Kat. The assistant director of operations goes by Frag Off.

The founder of the site said he went through the legal process of changing his name to Xavier Von Erck — a name he said he has used since he was a teen-ager. Von Erck said he was raised by his now-deceased grandparents, Dorothy and Ernest Erck, and that he adopted his mother’s family name when he was 15, shunning his father’s surname.

“Here’s the reason [for the name change],” he said. “It has nothing to do with the site. My father doesn’t deserve any credit for anything I’ve ever done. I don’t feel like using his name … is either fair or even just.” He said he picked the name Xavier because it seemed to “flow better with Von Erck.”

On another web site he operates, www.angrygerman.com, Von Erck, who is 27, said he’s single and lives in Portland with a roommate (who’s also involved with PJ) and two cats. He and describes himself as an atheist Libertarian who abhors nature and is very judgmental.

He said PJ screens its contributors and has accepted only 52 of what he said were thousands who had expressed interest. As for the cops who don’t want to use what his site collects, it’s their loss, he said. “Some law enforcement is not comfortable with it. … It’s an unfortunate choice, but it is their choice. They’re really wasting a great resource.”

He also disputes the suggestion that PJ’s volunteers are nothing but vigilantes and suggests a more appropriate comparison would be that of a neighborhood watch. When you see a neighbor’s house being broken into and call 911, he said, “You’re not taking the law into your own hands.”

He said ICAC is responsible for much of what he sees as misinformation spread among law enforcement about PJ. ICAC wants law enforcement agencies to collaborate with PJ only in cases where they can duplicate PJ’s results, he said.

“They want to work everything as double-work, create their own profiles and hope someone hits on them,” Von Erck said. The task force, he said, will spread whatever “misinformation they can to make us look bad.” He said ICAC tells officers during training that evidence gathered by PJ “can’t be used in court.”

“They need to spend more time on going after predators instead of trying to attack us,” he said.

The chat room into which Jane Patterson’s fictitious 13-year-old cheerleader stepped six months ago is part of a realm Martin Purselley, who heads the Tarrant County District Attorney’s computer crime unit, likens to a too-good-to-be-true world for child molesters.

“If you’re a pedophile and you want to have access to kids, go to Xanga or MySpace,” Purselley said, referring to two of the biggest social networking sites on the web. “Right or wrong, they [the teens and young adults who post personal information about themselves] put way too much information out there. It’s so open, the guys who like to be around kids, they have to be in heaven.”

“If you put your head in the sand, you’re not going to see it,” he said. “These guys, as [Jane Patterson] discovered, are out there.”

Patterson isn’t a member of Perverted Justice, just a curious mother of three who wanted to know if what she saw on Dateline could possibly be taking place in North Texas. When she found out it was, she called police.

“I started by calling the non-emergency number, and I got passed all over the P.D. Finally, Crimes against Children passed me to Computer Crime. Several detectives seemed interested, but the ball got dropped,” she said. “When no one contacted me, that’s when I gave up on the P.D.” and called the Weekly.

After the Weekly started asking police and prosecutors questions about Patterson’s complaint, they got interested again.

Fort Worth police describe it differently. “As far as us dropping the ball, that didn’t happen,” said Lt. Kevin Rodricks. “We’ve got the ball now.”

Police have since asked Patterson if they could assume her online identity and see if the suspect would hit on them as he had on her. They also interviewed Patterson again and asked her for her hard drive to make sure what she was telling them was legit.

Their main concern was whether Patterson, who said she doesn’t know the suspect, “had some kind of bone to pick,” Rodricks said. “And apparently those concerns were kind of allayed. She doesn’t have anything against this guy.”

A vice officer went online and tried to make contact with the suspect. At first, he had no luck. Later, when contact was established, the officer found that the once chatty man had grown cautious. “The guy’s not falling for the bait,” Rodricks said.

Police are also worried that someone else, a relative or a person with access to the man’s computer, may have been posing as him online. “Anyone who had access to that computer could be the villain in this,” Rodricks said.

Police are now in the process of obtaining a grand jury subpoena for the man’s ISP records — computer records that would presumably show whether the person who Patterson thinks solicited her fictitious 13-year-old is the person who owns the account involved in the chat. At this point, there’s no way to tell if the investigation will end in an arrest or a determination that the computer was being used by someone besides the suspect, or whether a wannabe predator will have gotten away. However it is resolved, Patterson’s case appears to be one of the first times police in Tarrant County have attempted to make a case partially on evidence gathered by civilians against a suspect in an online solicitation case.

Rodricks oversees a crew of 10 vice officers, three who work days and seven who work nights — and they devote much of their time to more traditional vice operations, like busting street prostitutes. But two officers are devoting substantial amounts of their time to online solicitation cases, he said.

Beyond his concerns about the facts of this particular case, Rodricks worries that publicity about civilians outing child molesters might flood his small unit with more cases than it could handle. “It could just open up the floodgates,” he said. And he also worries that a suspect might learn the identity of the adults who are posing online as minors. “There’s a dangerous element to it. Some [predators] are very savvy and could figure out where these people are.”

Under normal circumstances, the Weekly would have called the suspect in Patterson’s scenario and asked him about the chat. But doing that might have tipped the man to the police investigation. So the paper chose not to contact the man and also to omit details from the chat — such as the fictitious name Patterson used, the chat room where the conversation took place and the suspect’s user name — that might do the same thing.

Rodricks wishes groups like Perverted Justice and people like Jane Patterson “would leave [investigations like] this to us, the professionals.” In this case, so far at least, the professionals don’t have much to show for their efforts. In the months since Patterson went to the police, Dateline has broadcast another installment of its “To Catch a Predator” program — and local media have covered a number of similar operations carried out by Lake Worth police and others. Patterson believes all the publicity may have made the man who chatted with her more cautious.

“You hit the panic button and call the cops and they didn’t do anything,” she said. “If they had gotten on it immediately, they probably could have gotten him.’’

You can reach Dan Malone at danmalone@fwweekly.com.