Her nightmares are less like dreams, more like memories of things that actually occurred, terrible recollections conjured in the wee hours while she sleeps.

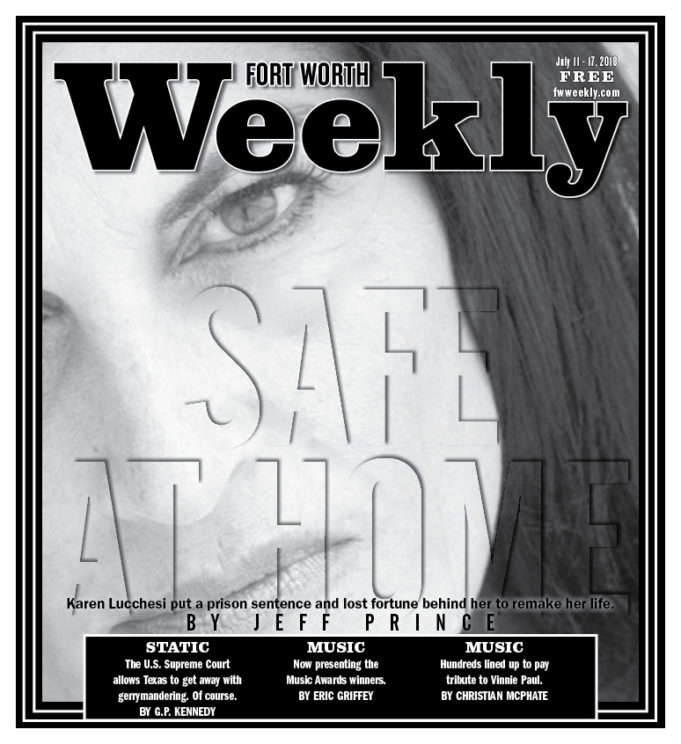

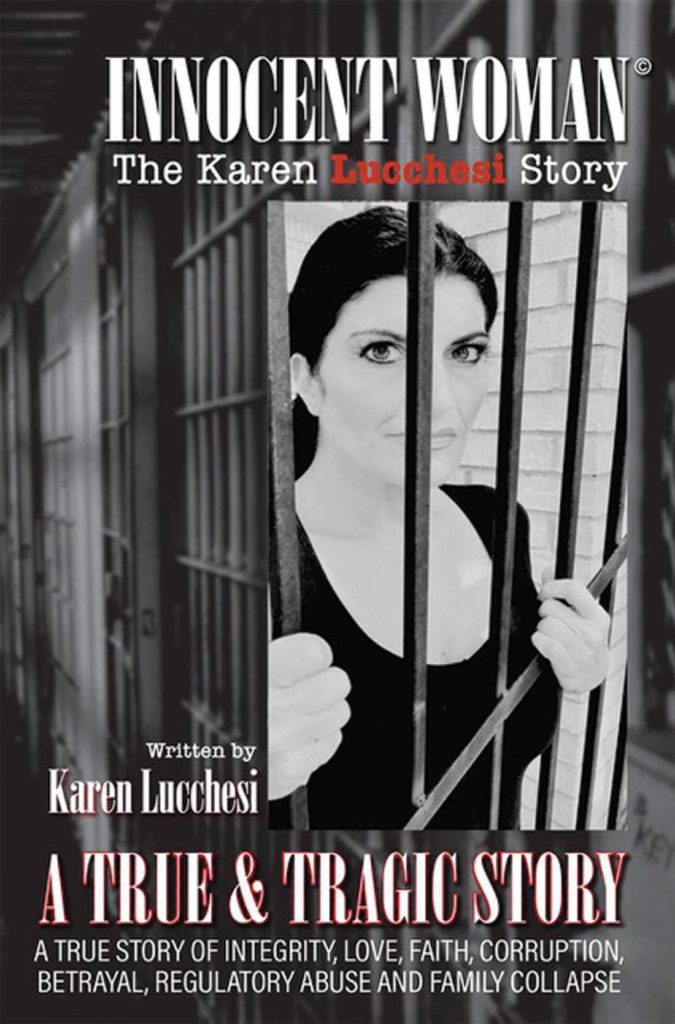

Karen Lucchesi kept those nightmares away for years by working hard each day and dropping into bed exhausted at night. Writing her recently self-published memoir Innocent Woman changed things. An immersion into her past during this yearlong writing stint rewarded Lucchesi with Amazon-bestseller status and a head full of anxiety.

“I’m remembering things I had put in the back of my mind,” she told me over tea and cookies one recent afternoon. “Maybe that’s why I never wrote the book before.”

As the 2000s began, Lucchesi was living what most people would consider a dream. Dark haired, fit, and attractive, the businesswoman in her 30s was popular in her Colleyville community and lauded for her charitable work. She had founded several spas and salons in North Texas and was in the process of selling her La Plaza Wellness Center in Colleyville for more than $8 million.

The good times dissolved after a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agent accused her of money laundering in 2003. Lucchesi believes she was set up – framed – by a conniving federal investigator and an unethical lawyer. Lucchesi wasn’t too worried at first. She had what she considered ironclad proof of her innocence. Rather than take a plea deal, she sought a trial, figuring innocent people went free. Instead, a jury convicted her after a one-day trial, and a judge sentenced her to six years. Her term began on Jan. 30, 2004.

Lucchesi served most of her time at Federal Medical Center Carswell, a women’s prison in Fort Worth.

In 2007, she cooperated with Fort Worth Weekly reporter Betty Brink on two cover stories that spotlighted how corporations were boosting profits by relying on federal prisoners as captive labor pools and the medical neglect of those prisoners. Since 1999, Brink and the Weekly had been publishing pieces critical of the culture of abuse at Carswell.

In apparent retribution, Carswell officials transferred Lucchesi to a prison in Florida – far away from relatives who visited her regularly and kept her spirits up.

Lucchesi was freed from prison in 2009.

During a wide-ranging conversation with me in May, she described her book-inspired nightmares in stream-of-consciousness non-chronological bursts: “The feeling. The first day I went in there. Hearing the door shut. Knowing my family was gone. Lying in the top bunk. These florescent lights shining down on you 24-7. Staring at the ceiling. The emptiness. The night they pulled me from my bed and put me in shackles and handcuffs. Not knowing where you’re going. Going in this big bus. Sitting in this room that is roach infested. The guards pulling me out, taking me there, taking me here. Feeling hungry. The mental abuse. Walking down a long tunnel. Am I ever going to get home? Running. Someone chasing me.”

One particular nightmare – based on fear rather than memory – has caused her to wake up screaming.

“It’s a dream that I’m at home with my family and the guards come in my room and take me back to Carswell,” she said.

These vulnerable moments pass quickly. The fiery Italian shakes off the bad dreams, anxiety, lost wages, and tarnished reputation and takes care of business. She is shilling her new book that she intends to see made into a movie. She is a business owner, professional speaker, and major player in efforts to establish a new Triple-A baseball league in Texas and beyond. She also volunteers with the Innocence Project, a national nonprofit legal organization designed to exonerate the wrongly convicted.

The prison stint interrupted her life but didn’t ruin or define it, she said.

“Anyone can do anything they put their mind to if they have the right attitude,” she said. “Determination, faith, and passion are my key beliefs. I got over this and kept on going.”

*****

The alleged money laundering that landed Lucchesi in prison could have been the result of a business relationship that began with a chance meeting two decades ago. The blandly titled but hard-hitting and emotional Innocent Woman: The Karen Lucchesi Story describes how Lucchesi bumped into a local attorney named Ani at a mutual friend’s Christmas party. Ani and his wife, Lisa, introduced themselves to Lucchesi and talked for a few minutes. Three months later, Lucchesi needed an attorney for a small business matter and asked her friend for Ani’s phone number.

Lucchesi hired him for various legal services over the next few years. In 2000, Lucchesi, her boyfriend at the time, and their dog needed a place to live. Lucchesi said Ani and Lisa owned several acres of land near Keller with a big red barn. Lucchesi made them an offer: She would remodel the barn into a livable house and pay expenses in exchange for being allowed to live there free with her now ex-boyfriend and dog for a few years.

During this time, Ani allegedly told Lucchesi that he and his wife were into recreational drugs such as cocaine and a “swingers” lifestyle. Lucchesi said she wasn’t interested in either and distanced herself from the couple socially, although she continued to hire Ani for legal services on occasion and also attended some counseling sessions with Lisa, a Colleyville psychiatrist, during a rough patch between Lucchesi and her ex-boyfriend.

Things were great for Lucchesi’s business life. Glamour, Redbook, and Marie Claire wrote features on her wellness centers. She was negotiating with two different investor groups seeking to buy the La Plaza center, and Lucchesi relied on Ani to handle the financials. She needed a bridge loan to tide her over until the sale went through, and Ani allegedly introduced her to a man named Jesse. Ultimately, Lucchesi secured a loan elsewhere and told Ani she didn’t need Jesse.

In January 2003, Lucchesi said she noticed her Wells Fargo Bank statement listed a $3,840 check written to a video company. She called the company, and a manager assured her they had neither received nor cashed such a check. Lucchesi went to the bank, spoke to several employees, and filed a notarized fraud report.

Two months later, Lucchesi decided after years of nonstop work that she deserved a short vacation to Cancun, Mexico. The La Plaza sale was about to go through, and she needed a break. After two days at the beach,she received a call from her mother on March 6. Two DEA agents had showed up at their house looking for her. The agents allegedly said it was no big deal and said they would check back later.

Lucchesi, as she wrote in her book, had no idea what the visit was about, but she wasn’t worried. She had no involvement with drugs, she said.

“I was in vacation mode, dang it!” Lucchesi wrote in her book “We finished our conversation, and I hung up without giving it another thought. Little did I realize that would be my last night of excellent sleep for many years.”

The following day, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram published an article saying Ani had been arrested for money laundering. The story mentioned his ties to Lucchesi.

Lucchesi hired a new attorney, who told her that the DEA agents had found Lucchesi’s personal and corporate checks in Ani’s possession at the time of his arrest. Lucchesi still believes he stole them.

Oh, and Jesse – he turned out to be an undercover DEA agent.

Ani and his wife were both in trouble. Years earlier, the Texas Medical Board had reprimanded Lisa for using illegal controlled substances. Medical board records and Star-Telegram reports show a long history of disciplinary actions taken against Lisa beginning the year before Lucchesi was arrested.

In 2002, according to board documents and published reports, the medical board reprimanded Lisa after her arrest on suspicion of driving while intoxicated and possessing a controlled substance. Records indicate that she was placed on probation for seven years and ordered to undergo psychiatric counseling and attend Alcoholics Anonymous. In 2008, records show her failure to submit to a drug screening prompted a $5,000 fine and medical license suspension. A positive drug test in 2009 prompted another $5,000 fine and an order restricting her from prescribing certain classes of drugs. In 2013, the DEA cited her for records-keeping deficiencies, and the medical board ruled that she had prescribed dangerous drugs to herself and controlled substances to her husband.

Lucchesi believes Ani made a deal with the DEA to set up Lucchesi in exchange for a lenient sentence for him and Lisa.

Why would a fed do that? Lucchesi said her success and semi-celebrity status gave the agent something to brag about.

“It’s sad that the government protects the guilty people because they want a name or they want to target someone,” she said.

At first, Lucchesi cooperated with the DEA, providing evidence to prove she wasn’t involved. It was the first of many mistakes, she said. Her book covers this period of her life in stomach-churning detail.

By the time you discover some government agent has you on their radar, it is too late! They have already made their minds up without cluttering the process with your input. … This is our broken judicial system. Accusation alleges guilt. You have to prove your innocence, even though the law says they must prove your guilt. You’re condemned without saying a word. A decent prosecutor with an axe to grind can easily compel a grand jury to indict whomever the prosecutor suspects, and the circus begins. As the joke goes, my life became a ham sandwich, as any decent lawyer can get a grand jury to indict one.

Looking back, Lucchesi realizes she was naïve.

“I was at the peak of my career,” she said. “I was offered $8.4 million on one of my centers, and I had three more to sell. Life was great. This happens, and my thought was, ‘What do they want?’ I will show them information to show I didn’t have anything to do with this. I’m not thinking it was anything serious. I believed in the justice system.”

Justice appeared to be on vacation as well.

“If an overzealous regulator makes up a fake crime to target you, you are going to go down,” she said. “The things I’ve learned going through the court system, hopefully this book can maybe warn or help people and show them this happens.”

Three years into her prison sentence, and the highest court in the land, the U.S. Supreme Court, noted numerous problems with the prosecution and vacated Lucchesi’s sentence. Vacating or setting aside a conviction means the original prosecution doesn’t apply, although prosecutors can seek a new trial. No new trial was sought in Lucchesi’s case, but the system allowed her to remain in prison for two more years before being released.

A federal employee had been put in charge of overseeing La Plaza after Lucchesi was convicted. He cancelled the pending sale, even though the buyers still wanted to purchase the property, she said. Then he shuttered the doors, auctioned off everything, and sent her a check for $3.47, she said. Hundreds of thousands of dollars from the auction were used to pay federal “fees,” she said.

After her release from prison, Lucchesi sued Ani and his wife in civil court. Ani died not long afterward. Lucchesi won a $2.5 million settlement but hasn’t received any payments from Ani’s widow, Lisa, who still practices psychiatry in Colleyville. I left messages for her but did not hear back by press time.

As part of the settlement, Ani stated on record that Lucchesi didn’t participate in the money laundering. Ani, while being unknowingly recorded during Jesse’s investigation, can be heard at one point telling the federal agent that Lucchesi wasn’t involved in the laundering.

*****

The white-brick two-story house in Colleyville where Frank Lucchesi and longtime wife Catherine Lucchesi have lived since 1995 is impressive with its circle driveway and well-established trees. The family settled into this beautiful home after Frank retired from professional baseball, where he spent decades as a player, coach, and manager (including a managing stint with the Texas Rangers in the 1970s).

I had visited the house in the late 1990s to interview Frank for a profile I was writing of him for the Star-Telegram. I spent an afternoon hanging out with the fast-talking, irrepressible, buoyant Frank. He was retired at the time, although he spent most days charming customers as the official greeter at his daughter’s spa.

Frank took me to the spa to meet Karen that day. She was busy and not particularly talkative but greeted me warmly and carried herself with confidence and go-get-’em authority. I remember telling Frank afterward that his daughter was impressive. He beamed. She was the youngest of his three kids, he said, a relentless worker with intelligence and charm.

Several years later, I was surprised to hear she had been arrested and sent to prison.

All these years later, I found myself back in Frank and Catherine’s home, interviewing them for this story. Frank, now 92, is a shadow of himself. He suffered depression along with strokes and heart attacks in the years since his daughter was incarcerated. His short-term memory is fading and he stays quiet. He is on a permanent feeding tube, can’t swallow, and finds it difficult to talk.

Karen and Catherine blame his physical unraveling on the stress he experienced during the ordeal.

“When it happened, he never talked,” Catherine said while sitting on a couch beside her husband, who listened without showing emotion. “All he did was sit here and never say a word, never ask a question. He just built this shell around himself. Karen was his baby, the baby of the family.”

Lucchesi lives near her parents’ house and makes daily visits, just as they once made regular visits to her at Carswell. Those visits weren’t easy, requiring several hours of clearance and waiting in lines. Sometimes, they waited hours just to be told that they wouldn’t be able to visit that day for one reason or another.

“Just to go to the prison to see her, you are treated like you’re a criminal,” Catherine said. “There was really no respect from them. There were a few who were pretty decent, but overall it was humiliating. It was a long struggle.”

The frustration would fade when they saw Karen.

“She always had a smile on her face when we saw her,” Catherine said. “She never showed pain.”

Karen Lucchesi kept a rock jaw, shunning tears and fears. She made her prison walls bearable by becoming active. Surrounded by depressed, neglected, and medically deprived women, Lucchesi relied on her experiences with running wellness centers to begin a program to inspire fellow inmates.

“I started working with women in the hospital and doing exercise classes to motivate people,” she said.

That led to more activism. Lucchesi reported medical issues with prisoners that weren’t being addressed, including her own. (She suffered from lupus and high blood pressure.)

She reported other problems as well. The white letters on the computer keyboards had worn away, making it difficult to type emails. Lucchesi’s request for replacement keyboards was denied. Her family offered to provide several new keyboards. That offer was refused. The inmates were being charged by the minute for using computers, and slow, difficult typing meant more profits for the prison.

Those complaints weren’t always appreciated. Lucchesi didn’t care. She’d grown tired of suffering and seeing what she considered daily injustices. She believed many of the inmates – like her – had been wrongly convicted. She disliked how corporations and prisons had aligned to exploit prisoners for cheap labor.

The breaking point came after a 75-year-old inmate fell in her cell and lay there for hours, eventually dying because of medical neglect, Lucchesi said.

She contacted the Weekly’s Brink, whom Lucchesi knew faintly through business connections.

“My business had won some awards, and we had crossed paths,” Lucchesi said.

Brink wanted to write about the prison labor issues, and Lucchesi was eager to cooperate.

“I compiled a bunch of information and gave her a lot of research on Unicor, the prison system making billions of dollars off of prisoners,” Lucchesi said. “That’s why they give people such long sentences, because it’s a big money-making business.”

A prison counselor assured Lucchesi that her freedom of speech was protected despite her being incarcerated.

“I said, ‘Will there be any repercussions?’ ” Lucchesi recalled. “She said, ‘No, you have freedom of speech.’ If she had said, ‘Well, you never know,’ I would have probably said, ‘Betty, keep this on the down-low.’ ”

Instead, Lucchesi gave Brink permission to publish her name (“A New Kind of Wage Slave,” Oct. 17, 2007).

“She did a great story on it,” Lucchesi said.

Retribution was quick. At 2:30 a.m. not long afterward, guards rousted Lucchesi out of bed, shackled her, put her on a Bureau of Prisons bus, and drove her to a holding facility in Oklahoma. After a month there, she was sent to the Coleman Federal Correctional Center in Florida.

“They shipped me away from my family,” Lucchesi said. “It was payback. My parents were [at Carswell] religiously four days a week. Everyone at that facility knew it because no one else really had that.”

This was done despite the fact that, after the trial, U.S. District Judge John McBryde had sentenced her to 78 months in prison while stipulating that she serve her time at Carswell, a full-service federal prison hospital for chronically ill women. Lucchesi’s combination of lupus and high blood pressure could be deadly without proper medical care.

The stress on Lucchesi’s family, already severe, soared. Fractured emotions manifested themselves physically.

“If I had that part to do over again, I wouldn’t have allowed my name in that article,” Lucchesi said. “That triggered my dad’s first heart attack when they shipped me away. My dad’s health was never the same after that. He was the most vibrant, lively person. You know how he was. My mom told me he was never the same man. His health deteriorated after that.”

Heart attacks and strokes would return to Frank again and again.

“ I feel responsible for his [poor] health, and that’s what triggered me to write the book,” Lucchesi said. “I knew I had to tell the story and do it now while he is here. I had been approached by many authors to take my story and write it, and I never did it. One night, I just started writing and couldn’t stop. I spent nine months or so of nonstop writing. Parts of it I had blocked out. I dealt with the trauma by putting a wall up and repressing the memories.”

She can still repress them in her waking hours. It’s nighttime when the wall comes down.

“I had always had some nightmares after coming home over the years, but they were so strong when I started writing the book, so vivid, night after night,” she said. “That was hard.”

Tears don’t accompany the terrors. Lucchesi cried plenty after her arrest, but since that first day in prison, she toughened up and resisted being vulnerable emotionally. She hasn’t cracked yet.

“To this day, I’ve never cried,” she said.

Brink’s Carswell stories cast a critical eye on the prison for years. Prisoners still contact our newsroom to report problems there. Did Lucchesi’s whistleblowing and Brink’s reporting lead to changes? Lucchesi doesn’t know.

“It brought more awareness,” she said. “Something I’d like to do is follow up with that and see where things stand. Not being on the inside, I’m not sure if anything was corrected.”

*****

In Chapter 21 – entitled “Free at Last” – Lucchesi expresses joy at being freed from prison, mixed with fury at being detained in the first place. The author makes it clear she isn’t afraid to call out the people involved in her arrest, conviction, and incarceration. She names names throughout the book – including the DEA agent, prosecutors, and judge – and supports her claims by reprinting trial transcripts, court documents, and various news reports and articles.

I was locked up for 2,190 days. That is 52,560 hours of my life –– gone. Though excited and anxious to finally go home, I found it difficult to say goodbye to my close friends and bunkmate. I met some incredible women who suffered from unforgivable injustices at the hands of our government.

I reflect, even today, through this book, radio shows, and speaking engagements on how we, as citizens of America, are really not America. Our government is sadly America, not the people. I had my rights stripped away, a fake crime made up against me, and had crooked lawyers and an unethical judge determining my future. After all that, I made it to the highest court in America which declared my constitutional rights violated, vacated my sentence, and remanded my case to lower courts, only to have the lower court deny the Supreme Court’s opinion.

Unlike many ex-cons, Lucchesi found a safety net waiting. One of her staunchest supporters during her trial was local real estate investor Mike Costanza, whose holdings includes several properties in the Stockyards.

Costanza and some of his business partners had developed a shopping center in Colleyville and sold it to Lucchesi years before her arrest.

“I got to know her,” he said. “She was a hardworking woman. When I heard what happened, I said, ‘That’s not the Karen I know.’ ”

He began looking into the case and was troubled by what he saw as an overreaching DEA agent working with an unethical attorney and his wife trying to get out of trouble.

Lucchesi “and her family were a little naïve in trusting the system and not getting good attorneys,” Costanza said. “I can’t imagine how any juror who saw the evidence would ever convict her, but none of the evidence was allowed. Her attorney didn’t put up a fight and didn’t do any objections. She was railroaded right into jail. I completely believe she was 100 percent innocent.”

Several job offers were waiting on Lucchesi upon her release from prison. She chose Costanza, in part because of his tenacious support.

“He is a veteran and believes in America and is very patriotic,” she said. “When he saw what happened, he really fought for my cause.”

Costanza partnered up with Lucchesi on The Palace Room, a 12,000-square-foot event center next to Billy Bob’s Texas, but Lucchesi, like her father, loves baseball. She couldn’t resist after former Texas Rangers outfielder Pete Incaviglia recruited her to join the Grand Prairie AirHogs, a minor league baseball team that Incaviglia managed.

First, though, she needed to be interviewed by Mark Schuster, who owned the team at the time.

“Pete Incaviglia said, ‘I want you to consider hiring somebody, but she has some issues,’ ” Schuster recalled. “I said, ‘Don’t tell me about the issues. Let me interview her first.’ I met with her and got along with her great. I felt like she would be a stellar addition to our team.”

After meeting with Lucchesi, Schuster asked Incaviglia to tell him about the “issues” – a federal conviction for money laundering.

Schuster was dumbstruck.

“I couldn’t see Karen as somebody who would do something like that,” he said. “I have a pretty good gut feeling about people. I didn’t believe she was guilty. I said, ‘I’m going to ignore what happened to her and believe that she is a solid human being.’ She is. She is as nice a person as you’ll ever meet.”

Now, he describes Lucchesi as “family” and a remarkable role model.

“I feel terrible for what she had to go through, now that I know the whole story,” he said. “That is a strong woman, and she is not bitter at all. I’m not sure I would be the same way.”

In 2008, Lucchesi became a vice president for AirHogs in the same league as the Fort Worth Cats. In the ensuing years, she moved to Laredo to help establish a new team and ballpark there and oversaw the food and beverage sales. She worked for a brief stint with the Cats. Three years ago, she partnered again with Schuster, who had become CEO at Ventura Sports Group, a private company founded in 2004 to acquire independent teams and stadiums. Schuster’s group is currently establishing the Triple-A independent Southwest League of Professional Baseball, and Lucchesi’s company, KRL, will oversee concessions and special events at the league’s stadiums.

The league is set to launch in April 2019. So far, teams have been announced in Dallas, Rockwall, Waco, and Joplin, Missouri. Eventually, plans call for the creation of 18 teams playing in stadiums that can be used year-round.

The stadiums “will be utilized for high school football with side-by-side soccer fields,” she said. “We are building a concert stage in center field. This is a good model that will sustain itself long term.”

League officials are negotiating with other Texas cities currently.

“Within the next couple of months, there should be a couple of big announcements,” Lucchesi said.

Her enthusiasm is overflowing when she talks about baseball and stadium development. The work ethic that Costanza marveled at is on constant display as Lucchesi juggles speaking engagements, charity work, and book promotions alongside developing ballparks.

Frequent visits with her parents involve a lot of talking about the future, she said. The past? Not so much. They’ve all focused forward. Nobody is more proud of Lucchesi than her mom, Catherine.

“She came home and is better than she ever was in strength, faith, and optimism,” Catherine said.

If Innocent Woman is made into a movie, the leading role should go to Sandra Bullock, who is a “tough cookie,” Catherine said.

Lucchesi is currently negotiating on various options for movies, with an eye on HBO, she said. Profits from the book or movie will be used to assist people who have been wrongly convicted, she said.

So who does Lucchesi envision portraying her in a movie?

“I don’t know, but they would have to look Italian,” she said.