Photographer Loli Kantor’s works have reached nearly every corner of the globe through notable museums like The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Photography Museum of Lishui, China; and the Lviv National Museum in Ukraine.

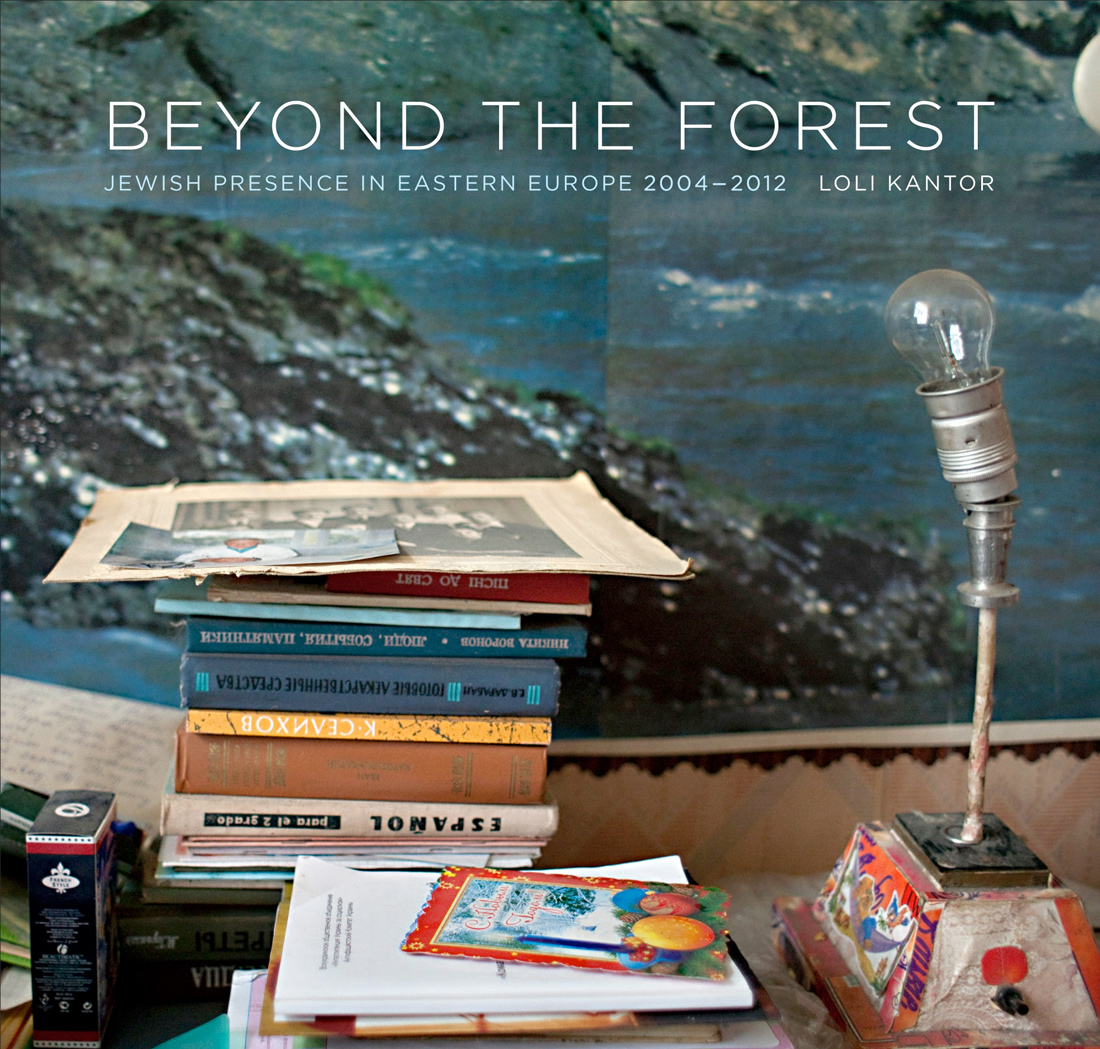

Her works have largely focused on local artists of all stripes. The Fort Worth resident’s documentary of Hip Pocket Theater actors and sets, Heaven on a Biscuit, was exhibited at Arlington Museum of Art in 2004. But for her first photobook on a university press, Beyond the Forest: Jewish Presence in East Europe, 2004-2012, Kantor drew inspiration from her long-deceased Jewish parents and a far-flung world that never left her memory.

In the opening chapter, “Presence,” Kantor pieces together her fragmented childhood. The short autobiographical section (five pages) is long enough to give context to the dozens of photographs to follow but not so long as to detract.

Her Polish father, Samuel Kantor, survived Soviet occupation during WWII but was not spared from wartime Russian labor camps. Loli’s mother, Lola, also Polish, was one of the few members of her family to avoid internment at Nazi concentration camps by living under an assumed name as an Aryan. The young couple met after the war in Munich (like many job-seeking Jews, surprisingly), marrying there in 1946 before resettling in Israel in 1949 and then Paris in 1952.

Kantor’s mother died giving birth to her in 1952. Samuel remarried twice and died in Israel when Loli was 14. The loss of her parents, along with the devastation of the Holocaust, meant that Kantor’s break with her family’s history was nearly complete. In 2004, she began traveling to modern-day Poland and Ukraine to document whatever Jewish presence was left.

The journey begins with “On the Road,” taken in 2009 near the Transcarpathia Mountains in Ukraine. The foreground is a muddy, smeared windshield that blurs the faint image of dark, pine-covered hills beyond. There is nowhere for the eye to rest. The feeling must have been shared by Nazi prisoners as they peered through wooden boards, crammed like cattle into trains as they headed east, like Kantor 70 years later, into the heartland of the Third Reich’s most infamous concentration camps.

The bulk of Kantor’s photographs are captured in the chapter “Plates.” The author’s ability to develop a narrative through images is masterful, but the unfolding isn’t chronological. Each photo jumps forward and backward in time. The first dozen pictures are in black and white, and a black border intentionally left in reveals that film, not a digital camera, was used. “Alfred Schreyer Tells His Story” depicts an old man asleep in a recliner, framed in the lower right-hand corner of the shot. There is a quiet feeling of dignity conveyed by his sharp suit and the strong overhead lighting. His surroundings are subtly out of focus. His countenance is serene.

Environmental portraits alternate with human portraits. “Targowa Street” reveals the family residence of the Kantor family before the war. On the left-hand page, an outdoor shot gives the perspective, head-on, of an apartment seen through a dark alley. The capturing of strong geometrical shapes highlights the building’s crumbling façade, cracked driveway, and a small heap of rubble in the image’s center. On the right-hand page, a nearly pitch-black picture takes us inside a dark household room at the same location. The silhouette of a human form is barely decipherable near the center. For all the negative space, the effect is somehow one of intimacy.

Halfway through the book, color photos of Jewish residents become the norm. Many of the photos naturally focus on synagogue life and cultural events. The side-by-side diptych of “Hanukkah Party” and “Passover Luncheon” couldn’t be more visually contrasted. While the “party” is a sterile, grayish close-up of a tray of silverware, the luncheon, to the right, is a meal overflowing with bright oranges, red wine, and green salads. The famine of one image is satiated with the visual feast of the other.

By the 92nd photo, the journey has come to an end. The author does not offer a warm, fuzzy conclusion to the search for a Jewish presence in Eastern Europe. It is the normalcy of the lives of these people that is most striking. Whatever scares were left by the Holocaust have long subsided into memories and stories.