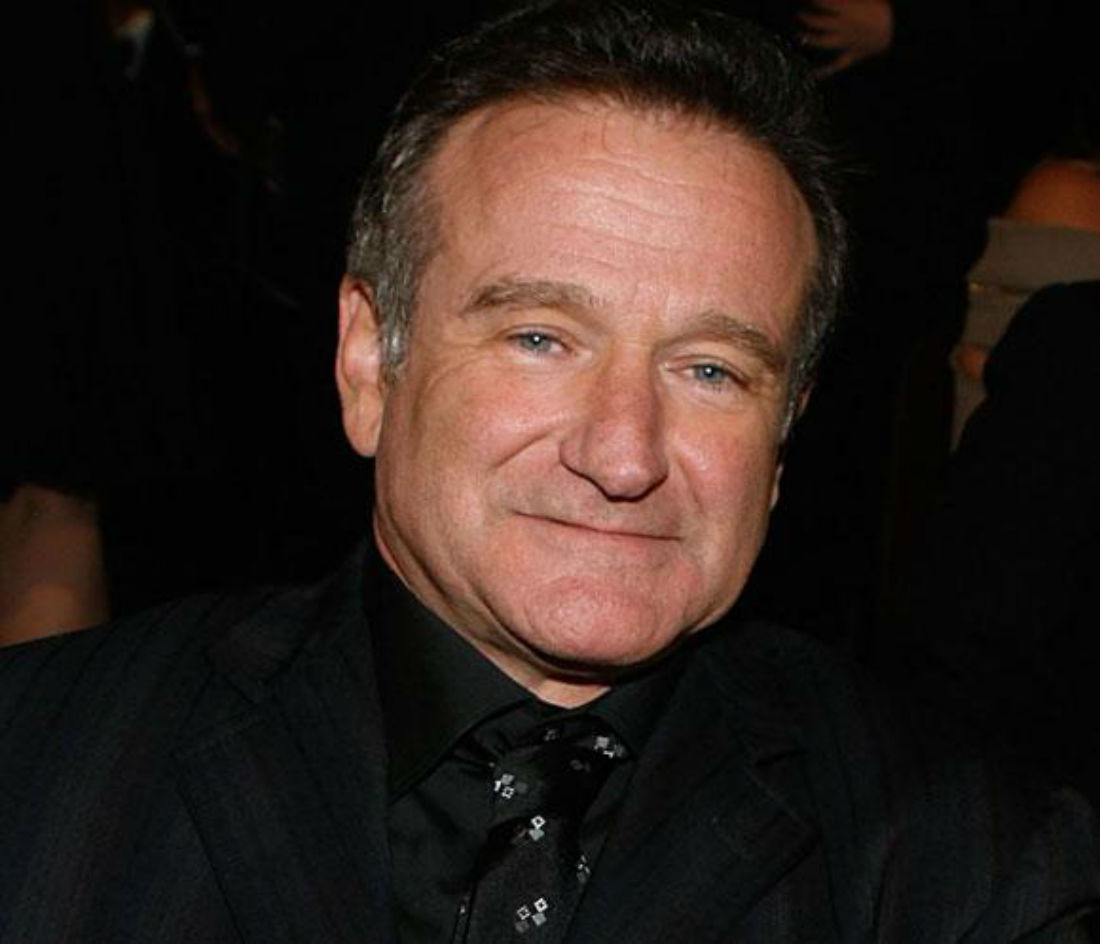

I was at the advance screening of The Giver last night that featured red-carpet interviews with the film’s stars, and Jeff Bridges burst into tears as he mentioned a dear friend he had lost. That was how I learned that Robin Williams had died at age 63 of what now looks almost certainly a suicide.

When I found that suicide was suspected, I thought, “Well, this is one time Robin Williams failed to surprise me.” But now I think that might have been wrong. Maybe the surprise was that he lasted 63 years. The man never concealed his demons, whether they were his battles with depression or his heavy drug use that resulted from it. The sobering thing is, Williams seemed to do everything right to stave it off: He talked about it openly, he sought professional help, he co-founded Comic Relief to help the less fortunate, he acted out his neuroses in front of all of us. Surely he knew he was loved, both by his immediate family and by the world’s audiences. Yet none of it was enough to keep him from hanging himself. Depression is a bitch. I’ve seen it up close, too, so I have a clue. If you’re depressed, get help from anywhere you can find it. Except don’t turn to alcohol and cocaine, like Williams did at various points. Cocaine is bad.

Of course, Williams made his early fame on the stand-up circuit and on TV’s Mork and Mindy, where he quickly established his manic style, with comic ideas, wordplay, celebrity impersonations, and funny voices bubbling to the surface faster than he could get them out. This quality made him intensely watchable, but his early film career was defined by him running away from that, with a starring role in Robert Altman’s box-office flop Popeye and a dramatic turn in The World According to Garp. Still, the world didn’t seem to take him seriously until he embraced what made him unique in Good Morning, Vietnam (for which he got his first Oscar nomination) and then harnessed it to the role of an inspirational teacher in Dead Poets Society. The latter movie came back to prominence earlier this year when Apple used one of his speeches from it in an ad that gave me chills during the Winter Olympics.

http://youtu.be/jiyIcz7wUH0

The quintessential movie performance by Williams remains Aladdin, where Disney’s animation proved to be the only thing that could keep up with his riffing. Still, when I heard of Williams’ death, one of the first things I thought of were those two dark performances he gave in 2002 in Insomnia and One Hour Photo. In both of those, he plays deeply abnormal men who are desperately trying to project normality to the world, only their desperation gives them away. To be fair, Kenneth Branagh first cottoned onto this quality of Williams’ when he gave him an uncredited cameo role in his delightfully pulpy 1991 thriller Dead Again, but Christopher Nolan gave it full force when casting Williams as the killer in Insomnia. That seems to be the one Nolan movie that people don’t care for, perhaps because it doesn’t have the period trappings of The Prestige, the mind-bending stories of Inception or Memento, or Batman. Williams is downright scary in this as a lethally smart man who snaps when he commits the murder but then methodically covers his tracks to get away with it. I’m less fond of One Hour Photo as a film, but Williams’ work there is the reason to watch it now, as his illusions of sharing in a perfect family (whom he only knows by processing their photographs) are shattered. His last truly great film performance was in this vein, too, in World’s Greatest Dad, which Jimmy Fowler blogged about here when it came out. There, he plays a failed writer who loves his son (Daryl Sabara) even though the kid is thoroughly despicable. When the boy kills himself via autoerotic asphyxiation — eesh — his dad passes off his own writing as his son’s saccharine diary and becomes a media celebrity. Bobcat Goldthwait’s satire is too cartoonish in spots, but Williams kept the main character grounded, a man who hates himself the more success he finds, because it isn’t earned.

Of course, he made a whole lot of crap, too. Take your pick: Patch Adams, Bicentennial Man, Old Dogs, The Big Wedding. I must admit to having a soft spot for Death to Smoochy. (Turns out I’m not alone in this.) During the climactic sequence, his character is severely injured, and someone asks him if he’s all right. He says, “I’m kinda fucked-up in general, so it’s hard to gauge,” just before he loses consciousness. The line has a different meaning now, but it still makes me laugh, God help me.

Tributes from Williams’ fans and fellow entertainers have poured in, and the one that got to me was Mindy Kaling’s tweet disclosing that she was named after Mork and Mindy. Everyone seems to have their particular memory of something Williams did. Mine is a Saturday Night Live sketch from 1988 (sadly not online) in which he played himself in 2011, broke and forgotten, being visited by his son (Dana Carvey, doing a Williams impression) for his 60th birthday. The aged Williams reflects on his lost fortune: “Maybe it was all those sequels to Good Morning, Vietnam that did it. Maybe Bon Jour, Beirut was too much.” He did make it to 60, but he never grew old. He spent his career spreading joy to so many people, but we all would have gladly given some of it back to help him get through another day. Since we can’t, we’re lucky to have so many laughs that he created to remember him by, and the thought that he’s finally at peace.

One cannot help but feel that he could have branched out to do other things (producing, directing) in the industry because he had the education and underlying talent for it. He was reportedly despondent over the cancellation of his return to TV sit com “The Crazy Ones” which was not bad as a sit com concept-although a little anachronistic and he reportedly had financial reversals including properties he was unable to financially maintain. I think that- at his level- he had more people dependent upon him than he could cope with and needed a better defined support system. Sadly– the country has changed since the 70’s and 80’s when he started his meteoric rise– and not for the better. There is less quality work and less optimism than I can ever remember. This is all very sad.