Pertussis, the deadly whooping cough that killed thousands of children in the early part of the 20th century, is making a comeback in Tarrant County and across the nation, and no one is quite sure why. But the disease is preventable by vaccine, which means it’s vital for children to get vaccinations and booster shots. Last year 10 newborns died in California from pertussis contracted from adults, and the state declared an epidemic.

No one has any clear explanation for the resurgence of a disease that’s been mostly under control for about 60 years. Two pioneering women doctors developed a vaccine in 1938, and by the 1940s the pertussis vaccine, combined with ones for diphtheria and tetanus, was being given to babies at two months. The so-called DPT vaccinations were soon required for kids to enter schools in every state. Childhood deaths from whooping cough dropped to below any statistical significance and stayed there until the 1990s, when the disease began to show up again in significant numbers in California, eventually spreading to other parts of the country.

No one has any clear explanation for the resurgence of a disease that’s been mostly under control for about 60 years. Two pioneering women doctors developed a vaccine in 1938, and by the 1940s the pertussis vaccine, combined with ones for diphtheria and tetanus, was being given to babies at two months. The so-called DPT vaccinations were soon required for kids to enter schools in every state. Childhood deaths from whooping cough dropped to below any statistical significance and stayed there until the 1990s, when the disease began to show up again in significant numbers in California, eventually spreading to other parts of the country.

In Texas, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of cases in the last few years but not in the number of deaths. “We are closely monitoring pertussis [statewide],” said state health department spokesperson Carrie Williams.

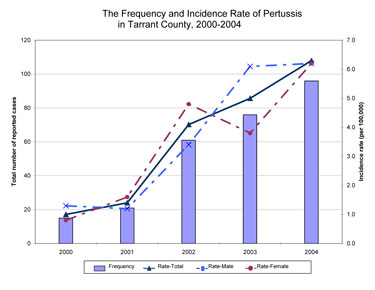

In Tarrant County, one infant death was attributed to pertussis in 2008; there have been none reported since. However, there has been a huge spike in reported cases here –– from 15 cases in 2000 to 312 in 2008 and 202 the following year, according to data from the Tarrant County Health Department. Similar preliminary figures for 2010 put Tarrant’s incident rate at about 15.5 per 100,000 residents, well above the statewide rate of 11 percent. By 2008, Rachel Wiseman, an epidemiologist for the state health department, found that pertussis cases were shifting from being well-distributed across the state to becoming “highly concentrated in the north to northeastern section of the state.” The 2009 Tarrant County communicable disease report showed that the rate of pertussis was highest among Hispanics, at 15.7 cases per 100,000 residents, followed by blacks at 12.1 and whites at 9.3.

Despite those figures, “Tarrant County has had good immunization coverage,” said Dr. Anita Kurian, the county’s chief epidemiologist. Public schools are one of the first lines of defense, because of state laws requiring children at several grade levels to show proof of various vaccinations and booster shots, including for pertussis.

However, a half-dozen Fort Worth school nurses are now charging that their ability to provide that defense is being severely hampered by the same problem-filled student records program that parents and teachers have already complained of for other reasons. Out of fear of retaliation, all the nurses who spoke with Fort Worth Weekly asked that their names not be used.

However, a half-dozen Fort Worth school nurses are now charging that their ability to provide that defense is being severely hampered by the same problem-filled student records program that parents and teachers have already complained of for other reasons. Out of fear of retaliation, all the nurses who spoke with Fort Worth Weekly asked that their names not be used.

The very frustrated and angry nurses say they fear an even greater upsurge in pertussis cases could happen here because the program, known as Connects, simply won’t accept critical health data and won’t identify those students who are noncompliant –– that is, those who are behind in their immunizations or who have never been vaccinated. (Some health providers believe that the problem is being exacerbated by adults whose childhood vaccinations have waned in effectiveness –– parents may contract a mild form of the disease and pass it on to their newborns before the babies have been vaccinated. Pertussis boosters for adults are now being recommended.)

“We do not have accurate data to send to the state or the county on any of these criteria,” one nurse said.

Worse, the nurses have no way of knowing which students need to be sent to clinics to get booster shots. “Connects will not recognize ‘compliance,’ and [unlike the old system that Connects replaced] will not generate a report with a list of students with missing immunizations,” the nurse quoted above said.

Kurian said the county works closely with the Fort Worth school district health nurses who report all cases of infectious diseases as well as reporting entering students — at whatever age — who have not been immunized. Nurses are required to send students whose immunizations are not current or do not exist to physicians or a health department clinic to get shots. Those students are not allowed back into school until they show proof of their immunizations. The district nurses must also report such “noncompliant” students to the state health department by December of each year. Failing to meet that deadline subjects the district to an audit, said state health department press officer Chris Van Deusen.

In a district with more than 80,000 students and only 109 nurses to keep track of all of the immunizations, along with performing many other duties, the nurses have their work cut out for them. They must also perform state-mandated screenings for vision, hearing, pre-diabetic indicators, and scoliosis on all of their students and maintain accurate health records on each student. Then, of course, they must deal with the unexpected: the illnesses and injuries that crop up each day.

Nurses also need to keep track of which students are exempt from immunization rules due to a doctor’s order or religious reasons. That is also difficult with Connects, they said.

“Whooping cough is here, and it is our greatest worry right now,” a veteran nurse said. But because of the widespread flaws in the program, she fears that many of the students who need to be vaccinated will fall through the cracks.

This is especially critical, these nurses pointed out, in a district with more than 60 percent of its students listed as Hispanic, the group with the highest rate of pertussis in the county in 2009.

Several nurses noted that the district has students from Somalia, Ivory Coast, Mexico, several Middle Eastern countries, and other countries where war, poverty, and dislocation make it less likely that children have been immunized.

With so many students’ records to keep track of, the problems with using Connects are magnified. The program times out too soon, these nurses say, freezes up often, and is “maddeningly slow to open,” one said.

“I put [data] in and go back, and it’s gone,” one nurse said. “I’ve been a nurse here for almost 20 years, and I’ve never seen a bigger mess. … I love my job, but this is the worst year I’ve ever had.”

With more than 1,500 students to oversee, she said the time that Connects consumes is one of her greatest complaints. “There are so many steps you have to go through to get to the pages you need to enter data that it takes forever. … And it’s very embarrassing if a parent is sitting in front of you waiting to withdraw their child, for example, and needing the child’s immunization record, and it takes me half an hour to pull it up — and then it’s inaccurate or not there at all.”

With the old system, all of the nurses interviewed said, the data, once entered, came up on the screen in seconds. The system, called SASI for School Administrative Student Information, has been described by the nurses and others as simple to use, fast, and, most importantly, accurate.

SASI could organize data in many different helpful ways, one nurse wrote in an e-mail to the Weekly –– “freshmen in alphabetical order, just sophomore boys, all new students, a teacher’s home room students … . We could ask it for data daily, weekly, who was out of immunization compliance, and it would spit out an immediate report. This is very important.”

SASI could organize data in many different helpful ways, one nurse wrote in an e-mail to the Weekly –– “freshmen in alphabetical order, just sophomore boys, all new students, a teacher’s home room students … . We could ask it for data daily, weekly, who was out of immunization compliance, and it would spit out an immediate report. This is very important.”

Connects cannot do any of those things, she wrote. Most critically, “we cannot ask the program to tell us who is noncompliant on shots. It is unable to do that. That is a huge omission.”

Another major difference, she said, is that SASI would catch and reject obvious errors in medical entries –– immunization dates that would have been before a student was born or that are in the future. But Connects isn’t programmed to do that, she said.

This nurse said that, as a test, she entered impossible dates in the system recently, “and the program accepted all dates and processed the student as compliant. I was aghast.

“I realized the entire program is not ‘computer literate’ at all,” she continued. “It will not do what any other program written for nurses would, should, and must do.”

SASI, in use for more than a decade here, was a product of Pearson Higher Education, a large educational publishing house. Fort Worth district officials have said they dropped it in favor of Connects because Pearson had notified the district that it would no longer service the system due to its age.

However, information from Pearson shows that the district might have been able to keep using SASI after all and saved a lot of money in the process.

When the Fort Worth district decided to replace SASI, officials put out a request for bids, and Tyler Technologies, a software firm based in Dallas, came in with the lowest cost: $4.9 million for a three-year contract for a multifaceted student information system plus $750,000 a year in maintenance and training fees. Superintendent Melody Johnson signed a contract with Tyler for the information system on May 20, 2008. Fort Worth named its version of the system Connects.

Johnson also contracted with Tyler for a new payroll software program that proved to be another expensive problem. For the first several months of 2009, the new software overpaid more than 2,000 current and former employees a total of about $1.5 million. It was eventually revealed that several employees in the payroll department had warned Johnson not to implement the program because it was full of glitches and not ready for prime time. Two of the whistle-blowers were fired and have sued the district.

Now it appears that Pearson offered Fort Worth and other districts a fix that could have kept the SASI system in operation here.

In 2008, following the company’s notification to its client districts that it would no longer service SASI, the company also announced it had made available something called the SASI Customer First Program, offering existing SASI customers a license, at no charge, for its upgraded student information system, renamed PowerSchool.

In a June 2008 press release posted on its website, Pearson announced that it had earlier made the offer to “reward the longstanding loyalty” of its old customers. Under the plan, Pearson wrote, it would “migrate existing SASI customers to PowerSchool Premier over the next two years on a schedule that is most convenient to the district.” All the district had to do, the press release stated, was to click on PowerSchools web site to begin the upgrade.

The Weekly contacted Johnson’s office to ask if she was aware of the Pearson offer before she signed the May contract but received no response.

Other districts found the PowerSchool program beneficial. Craig Wheaton, superintendent of the 27,000-student Visalia Unified district in California, wrote in September 2010 on the district’s web site that Visalia had accepted Pearson’s offer and switched from SASI to PowerSchool for $177,000 in maintenance and training costs. Wheaton wrote in an e-mail to the Weekly that his district’s technicians were satisfied with the program and were able to enhance it to “better meet the needs of our users.” And, “We saved $468,000 in license fees” under the SASI Customer First program, Wheaton wrote.

Visalia spent around $6 per student to switch to PowerSchool; Fort Worth spent $56 per head for Connects.

When the Fort Worth nurses sent their bosses a list of a dozen significant problems with Connects that needed to be corrected, they all told the Weekly, their supervisor, Linda Govea, responded that a new version of Connects, called 8.3, would soon be out and would correct all of the glitches

“Well, it is finally out, and it hasn’t changed anything for the better,” one nurse said. In fact, on March 30, just days after the new version was installed, the nurses got a message from Govea with a red flag. She said she had just received an e-mail from a nurse who was using a new section of the program to enter vaccine information only to find that the program transferred the information she had just entered to “all of her columns and rows instead of just the ones she had selected. … Please refrain from entering [information in that section] until this is fixed,” Govea wrote.

The message only added to nurses’ frustrations, “Connects is simply a mess, and we [nurses] are all exhausted trying to make it work,” one nurse said. The time they must spend on Connects is taking critical time away from their other duties, in particular their need to screen children for the state-mandated conditions and still be available for the daily crises, she said.

“We are all behind on our screening, and we have only two months left to fix these problems. … I know I have kids who are noncompliant. The state asks how many are compliant, and we can’t tell them. …We can’t screen them because we don’t even know they are here. And all of our complaints have fallen on deaf ears.

“We are all behind on our screening, and we have only two months left to fix these problems. … I know I have kids who are noncompliant. The state asks how many are compliant, and we can’t tell them. …We can’t screen them because we don’t even know they are here. And all of our complaints have fallen on deaf ears.

“This is not a priority for this administration.”

For the first two months of this school year, nurses couldn’t even get into Connects, the nurse and others said. The nursing staff was also left out of the first summer in-service training for Connects. When they finally got some training, she said, it was after school started, and they were pulled from their other duties, which threw them even further behind in entering immunization information into the program. Then they figured out that data entry itself could be a nightmare.

“As soon as I entered my immunization data, half of it disappeared,” one nurse said. The district’s first deadline for providing preliminary data to the state was October 31, she said. “We couldn’t do it,” she said. “We didn’t have accurate data.”

This nurse and others said they were told by their principals and health department supervisors to simply estimate the number of students who were noncompliant. “I told my principal, ‘I’m not going to do that.’ ”

She said nurses could lose their nursing licenses if they provided false data to the state. “I’m not going to put my license on the line,” she said. Four other nurses interviewed for this story said the same thing. All who spoke with the Weekly said that the district will not be able to meet the December reporting deadline this year.

Most of the teachers and other school workers interviewed for the Weekly’s earlier story on Connects (“Dis-Connected,” Feb. 16, 2011), as well as the nurses interviewed for this one, said it is time to replace Connects, just as four other Texas districts have done after encountering similar problems.

The Azle ISD used the Tyler Technologies program for an entire calendar year, said schools superintendent Ray Lea.

“We cancelled at the end of last year because the system did not perform as promised. That’s all I can say,” he told the Weekly, “because we are actively considering litigation.”

He went on to say that the school district is now using software provided by the Region XI Service Center and that they are very happy with it.

In Willis, near Conroe, Sharon Hill, administrative assistant to the superintendent, wrote to the Weekly that the school district cancelled its contract with Tyler at the end of the last school year, replacing it with software also provided by that district’s regional service center. The Georgetown district cancelled the entire program after about three months, citing the program’s multiple failures to perform what was promised. The Brenham ISD’s web site shows that Tyler’s program has also been replaced with software from its regional service center.

Willis superintendent Brian Zemlicka wrote in a July 2010 cancellation letter to Chris Webster, vice president of services for Tyler, that “over the past year we have faced many challenges” with the Tyler product, and because of that, “we will not be renewing our agreement” for Tyler’s student information service. The Conroe Courier reported in a June 2010 article that Willis school trustees had called the Tyler program a “dismal failure,” listing problems similar to those reported by the Fort Worth employees. Requests to Tyler for comments were not returned.

Larry Shaw, head of United Educators Association, the largest educational group in Tarrant County, has recommended that the Fort Worth district cancel the program, as he said is allowed in the contract if the system doesn’t perform as promised. UEA conducted two online surveys of their members regarding Connects and found that more than 70 percent of the 600 or more respondents — including teachers, data entry clerks, and nurses — blasted the program as a failure and called for it to be replaced.

Phone and e-mail messages to various Fort Worth district officials seeking comment for this story were not returned.

Trustee Ann Sutherland is pushing hard for a review and is highly critical of Johnson for failing to bring the issue before the board for a frank evaluation. “Just as with management’s cover-up with the payroll fiasco, review of the Connects roll-out has been postponed and postponed,” she told the Weekly. “Both the superintendent and board president [Ray Dickerson] ignored my request several weeks ago to place this item on the agenda of our next board meeting. Only after I raised the issue in a workshop has it been scheduled, for either [Tue.] April 12 or [Tue., Apr.] 26,” Sutherland said.

She has the support of trustees Juan Rangel and Carlos Vasquez as she calls for a review of the program, but not Judy Needham, who strongly supports Johnson and has made the Connects issue a personal crusade against Sutherland. After Sutherland wrote to the board last August pointing out the “depth of the problems with the health records,” she got a heated reply from Needham:

“Ann — did your Ph.D. make you an expert on nurses and ERP systems too?” Needham wrote. “It is easy to criticize, but solutions are needed here, and the district is doing that. Staff need time and support, not rocks thrown at them. It would be nice if you were a positive team player.”